Trump and his compliant allies in Congress took pride in the One Big Ugly Bill that they passed in early July. But it offers reasons for shame, not pride. The Trump bill finances tax cuts for the richest Americans by cutting food for schoolchildren and Medicaid for millions of children.

The Republican budget bill locks in benefits for the rich and hunger for children of the poor.

Imagine laughing, applauding, and feeling proud of this heartless bill! I

President Donald Trump, joined by Republican lawmakers, signs the One, Big Beautiful Bill Act on July 04, 2025 in Washington, DC. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the bill will cut federal spending on SNAP by around $186 billion over the next decade. Samuel Corum—Getty Images

Becky Pringle, President of the NEA, writes in TIME magazine about the shamefulness of this legislation.

She writes:

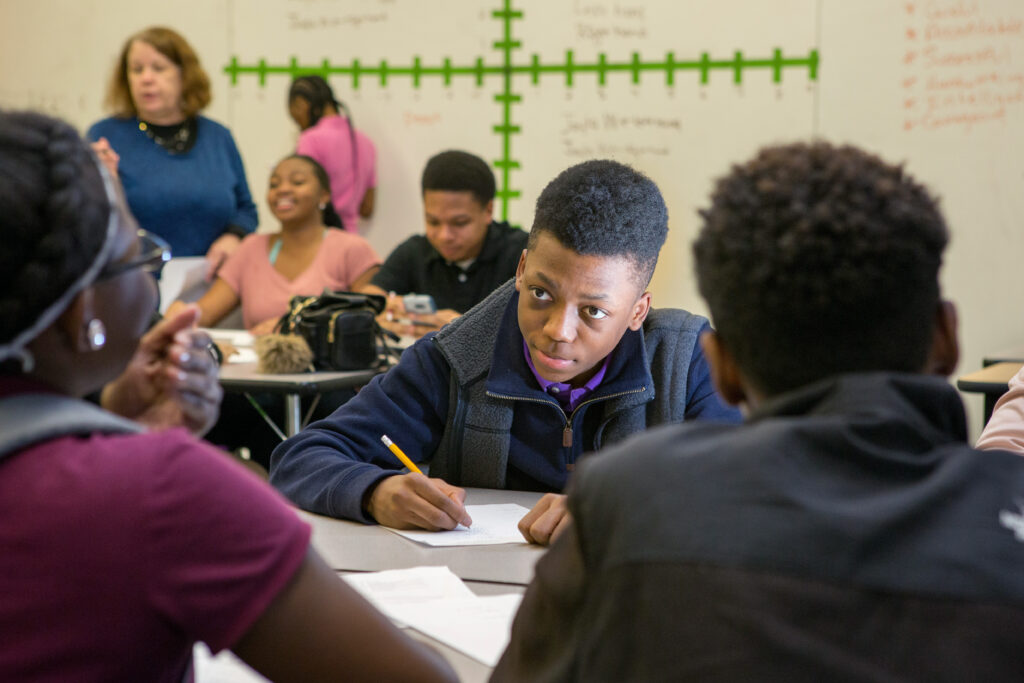

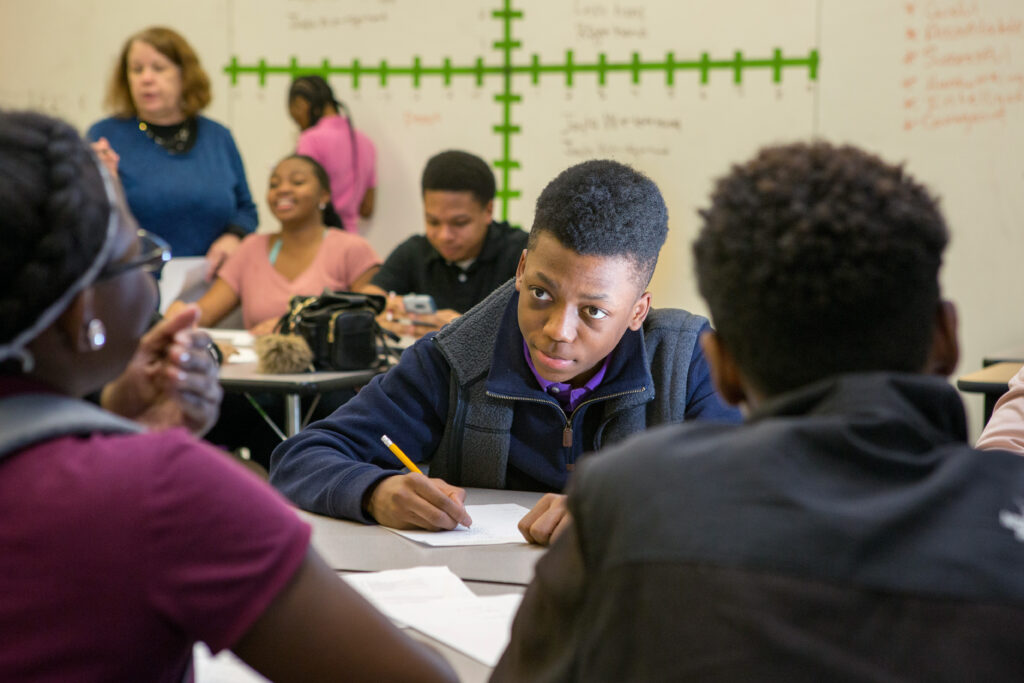

Hunger in America’s public schools is a real problem, and it is heartbreaking. As the head of the largest union of educators in the country, I hear stories almost daily of how kids struggle and how schools and teachers step up to fill the gaps. It’s the school community in Kentucky filling a Blessing Box with foods to help fellow students and families who don’t have enough. It’s the teacher in Rhode Island who started a food “recycling” program to ensure no food goes to waste and to give students access to healthy snacks like cheese sticks, apples, yogurt, and milk.

School meals are more than a budget line item. They are lifelines that help millions of students learn and grow. But as families across America prepare for the new school year, millions of children face the threat of returning to classrooms without access to school meals.

President Donald Trump’s newly-signed tax bill, which Republicans overwhelmingly voted to pass, slashes food assistance benefits via the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by an estimated $186 billion over the next decade—thelargest cut in American history. These devastating reductions will result in an estimated 18 million children losing access to free school meals.

The cuts shift the cost of school lunches to the states, costing them more than they can afford when they are already grappling with tighter budgets and substantial Republican-led Medicaid cuts.Twenty-three governors warned these cuts will lead to millions of Americans losing vital food assistance.

It’s hard to understand if you’ve never faced hunger, but millions of American children do not have access to enough food each day. In a recent survey of 1,000 teachers nationwide, three out of every four reported that their students are already coming to school hungry.

Our children can’t learn if they are hungry. As a middle-school science teacher for more than 30 years, I have seen the pain that hunger creates. It’s the student who skips breakfast so she can give it to her little brother. It’s the student who misbehaves because his stomach is rumbling. It’s the students who struggle in class after a weekend where they didn’t have a single full meal. Educators see this pain everyday, and that’s why they go above and beyond—buying classroom snacks with their own money—to support their students.

Free school meals represent commonsense and cost-effective public policy. They don’t just prevent hunger, they help kids succeed. Decades of research reviewed by the Food Research & Action Center shows that when students participate in school breakfast programs, behavior, academic performance, and academic achievement go up and tardiness goes down. When I stand in a room of bright and curious children, it breaks my heart that some of them are going without the food they need to learn and thrive—not because America can’t afford to feed them, but because adults in Washington decided they’d rather spend the money on tax breaks for the ultra-wealthy.

The cuts from the Republican tax bill will hit hardest in places where families are already struggling the most, especially in rural and Southern states where school nutrition programs are a lifeline to many. In Texas, 3.4 million kids, nearly two-thirds of students, are eligible for free and reduced lunch. In Mississippi, 439,000 kids, 99.7% of the student population, were eligible for free and reduced lunch during the 2022-2023 school year.

These are not abstract numbers. These are real children who show up to school eager to learn but are instead distracted by hunger and uncertainty about when they will eat again. America’s kids deserve better.

The National School Lunch Act of 1946 laid the foundation that public schools are places where children can receive a free breakfast and lunch each day. This shouldn’t be a partisan issue. For decades, Republican and Democratic administrations alike expanded school lunch programs, operating under the shared understanding that no child should go hungry at school in the richest country in the world.

But the extreme right wing of today’s Republican Party has walked away from that moral consensus—ripping away these programs to give another tax break to billionaires.

The Trump Administration’s authoritarian blueprint outlined in Project 2025 takes the anti-public education attacks even further by attempting to gut the Department of Education and to send tax dollars to private schools, and promoting ideologically-driven book bans and classroom censorship.

And now, as the Trump Administration and its allies work to destroy public education, they also have attempted tointimidate the National Education Association and our 3 million educators. They know we are powerful and vocal advocates for students and a formidable opponent to their attacks on public education. Last month, the relentless efforts of organized educators and our allies got the Trump Administration to release $7 billion in education funds it had tried to withhold.

Together, we will fight forward: for our vision where every student attends a safe, inclusive, supportive, and well-resourced public school, which includes nutritious meals for all students regardless of race or place.

We are educators. We don’t quit. We will continue to engage with school boards, town halls, state legislatures, and Congress to fight for students. Public education does not belong to politicians trying to dismantle it. It is for every student, parent, and educator who understands it has the power to transform lives.”