.errordiv padding:10px; margin:10px; border: 1px solid #555555;color: #000000;background-color: #f8f8f8; width:500px; #advanced_iframe_66 visibility:visible;opacity:1;vertical-align:top;.ai-info-bottom-iframe position: fixed; z-index: 10000; bottom:0; left: 0; margin: 0px; text-align: center; width: 100%; background-color: #ff9999; padding-left: 5px;padding-bottom: 5px; border-top: 1px solid #aaa a.ai-bold font-weight: bold;#ai-layer-div-advanced_iframe_66 p height:100%;margin:0;padding:0var ai_iframe_width_advanced_iframe_66 = 0;var ai_iframe_height_advanced_iframe_66 = 0;function aiReceiveMessageadvanced_iframe_66(event) aiProcessMessage(event,”advanced_iframe_66″, “true”);if (window.addEventListener) window.addEventListener(“message”, aiReceiveMessageadvanced_iframe_66); else if (el.attachEvent) el.attachEvent(“message”, aiReceiveMessageadvanced_iframe_66);var aiIsIe8=false;var aiOnloadScrollTop=”true”;var aiShowDebug=false;

if (typeof aiReadyCallbacks === ‘undefined’)

var aiReadyCallbacks = [];

else if (!(aiReadyCallbacks instanceof Array))

var aiReadyCallbacks = [];

function aiShowIframeId(id_iframe) jQuery(“#”+id_iframe).css(“visibility”, “visible”); function aiResizeIframeHeight(height) aiResizeIframeHeight(height,advanced_iframe_66); function aiResizeIframeHeightId(height,width,id) aiResizeIframeHeightById(id,height);var ifrm_advanced_iframe_66 = document.getElementById(“advanced_iframe_66”);var hiddenTabsDoneadvanced_iframe_66 = false;

function resizeCallbackadvanced_iframe_66()

Source link

برچسب: kindergarten

-

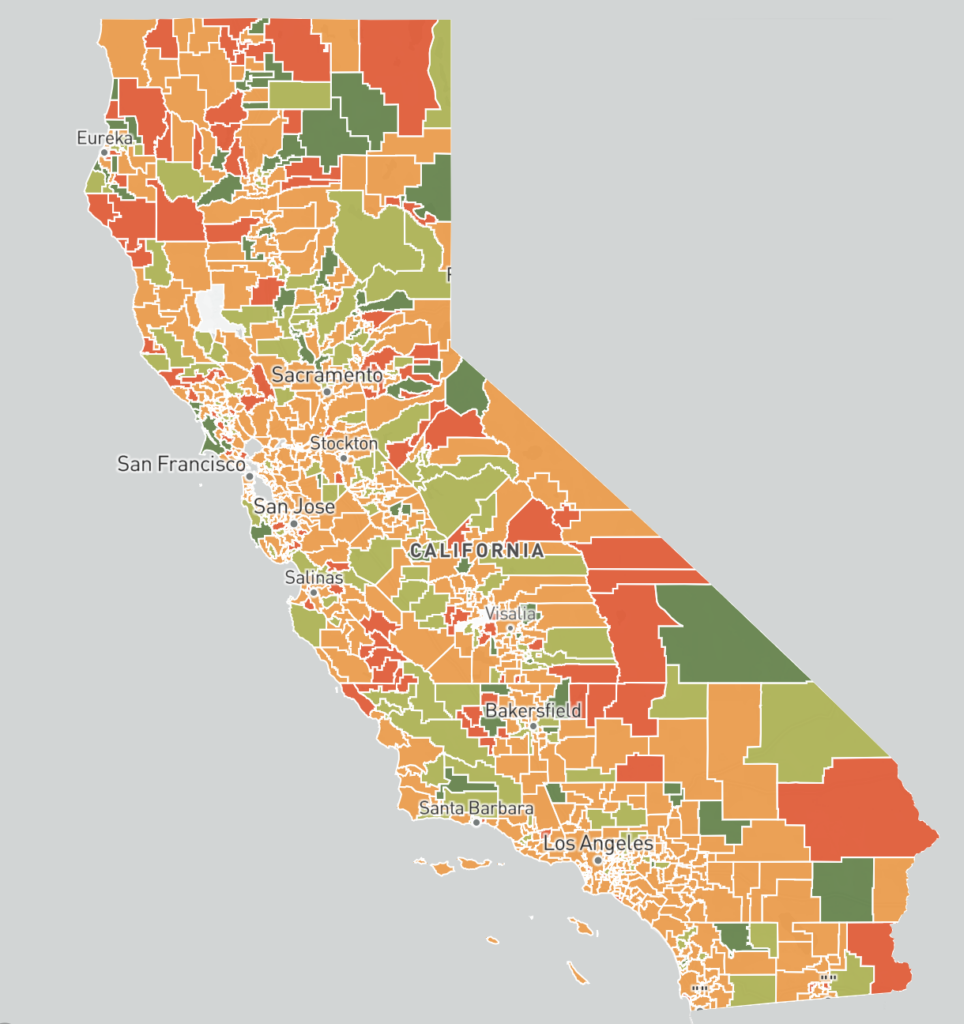

Kindergarten enrollment change from 2019 to 2021 in California

-

More kids skipping kindergarten post-pandemic

When Sunny Lee’s son was ready for kindergarten in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic had just begun. His school in Pleasanton, an eastern suburb of the San Francisco Bay, was holding classes online, like most others.

Lee opted out, after seeing what distance learning via Zoom was like for young children.

“I think the formatting was not ideal for young kids. It was just very disruptive and hard to keep track of, and there was just not that much engagement,” Lee said. “Socialization was a big reason for me to send him to school, and he wasn’t getting that.”

The following year, in 2021, when school was back in person, Lee’s son started first grade and her daughter started kindergarten. But after two weeks of school with Covid restrictions, she pulled both children out and began homeschooling them again. They returned to public school for the 2022-23 school year.

Lee’s children are among thousands that did not enroll in public kindergarten in California in 2020 or 2021, years when the state saw drops in kindergarten enrollment. And even among students who enrolled, many missed a lot of days in school.

NATIONAL disengagement from kindergarten

Kindergarten enrollment is down across the country. EdSource collaborated with The Associated Press on a national story about this. You can read that story here.

The pandemic triggered a different attitude about kindergarten, with a growing number of parents either opting for other programs, waiting a year to start kindergarten, or skipping kindergarten and beginning public school in first grade at the mandatory school attendance age of 6 years old.

Some parents were deterred by virtual learning; others were spooked by Covid risks and restrictions. Three years after the pandemic began, many parents still feel their children aren’t ready for kindergarten, after the pandemic disrupted and delayed their ability to play and socialize with others and learn skills from coloring and counting to potty training.

“The pandemic kids have really been struggling on the social side, with ADHD, anxiety and all that comes with not knowing how to play with other children,” said Deana Lundy, client services manager at Bananas, an agency in Oakland that helps families find child care and state subsidies for child care. “If you get a kid that was with grandma all this time and never even went to a child care center, it’s an even bigger barrier.”

Kindergarten is considered a crucial year for setting children up for academic success. Some experts worry that some of the children missing kindergarten will lag behind their peers in elementary school.

Kindergarten enrollment statewide dropped precipitously — 9% — from before the pandemic, 2019-20, to 2020-21, when learning was virtual in most school districts. In 2021-22, the latest year for which data is available, it stayed at relatively the same level as the year before.

Enrollment for 2022-23 was also below projections. The data currently available for 2022-23 lumps together children enrolled in both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten. Transitional kindergarten is a grade before kindergarten, open to some 4-year-olds. Though the overall numbers for both grades together increased by about 5% from 2021-22 to 2022-23, that may be partially due to the expansion of transitional kindergarten to include more 4-year-olds.

The California Department of Education declined to release the 2022-23 enrollment number for transitional kindergarten, adding that the data are set for release in early 2024, on the traditional schedule.

Those numbers are exacerbated by the number of students enrolled but missing a lot of school. According to Hedy Nai-Lin Chang, founder and executive director of Attendance Works, chronic absenteeism — when children miss more than 10% of days in the school year — surged to 40% among kindergarten students in the 2021-22 school year. Among all grades, the rate is 30%.

Chang said part of the reason absenteeism went up so much in kindergarten is that many children did not attend preschool during the pandemic, and because after the pandemic, parents were not allowed to go inside many schools.

“Parents now just drop them off at the door, and they don’t see what’s happening in the classroom. And now they also haven’t had their kids in preschool experiences where they might have understood the value of what you get from early learning,” Chang said.

“The pandemic kids have really been struggling on the social side, with ADHD, anxiety and all that comes with not knowing how to play with other children.”

Deana Lundy, client services manager at Bananas

All income groups opting out

When Sunny Lee and her husband chose to homeschool their children in both 2020-21 and 2021-22, they were concerned about distance learning and the risk of Covid. At the same time, they didn’t want their daughter to have to wear a mask because she has asthma, and they felt it could make breathing more difficult. To make matters worse, wildfire smoke began filling the air in the fall of 2021 and children weren’t getting much outdoor playtime.

On top of all of that, Lee’s husband is a physician and was working long hours during evenings and nights in the ICU during the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Because of school and my husband working in the ICU, the risk was really high, and the schedule was really hard,” Lee said. “They wouldn’t have gotten to spend much time with him.”

Lee contacted a friend in New York who homeschooled her children in New York to get help planning her lessons. Her children returned to school in fall 2022, when her daughter was in first grade and her son was in second grade. She said both her children learned to read at home.

“Looking back, I’m glad I did it,” Lee said. “I think they actually did better. I think they learned more and I was able to focus and hone in on the stuff they needed to learn.”

Some families like Lee’s who are deciding to delay or opt out of kindergarten can afford to pay for another year of child care or preschool or have the time to manage homeschooling.

But the trend to skip kindergarten is also growing among some low-income families who qualify for subsidized child care. Subsidies can be used for many different kinds of settings, including child care centers, home-based family child care programs, and informal care by friends and family.

Christina Engram was all set to send her 5-year-old, Nevaeh, to kindergarten this fall at her neighborhood school in Oakland.

Then she found out the after-school program didn’t have spots for all children and instead, there was a wait list. If Nevaeh didn’t get a spot, she would need to be picked up at 2:30 p.m. most days, and at 1:30 on Wednesdays.

“If I put her in public school, I would have to cut my hours and I basically wouldn’t have a good income for me and my kids,” said Engram, who is the sole parent of two children and works as a preschool teacher in another child care provider’s home day care program. Her younger child is 4 years old.

Christina Engram spends time at home with daughter, Neveah, 6, and 4-year-old son Choncey, right, in Oakland last month. Credit: AP Photo/Loren ElliottRather than potentially cut her work hours or quit, Engram decided to keep Nevaeh in a child care center for another year. She could afford it because she receives a state child care subsidy that helps her pay for full-time child care or preschool until her child is 6 years old and must enroll in first grade.

Engram was not worried about Nevaeh’s ability to do well academically in kindergarten, but she did feel that the girl needed some extra support and attention socially. In part, she said that could be because Nevaeh didn’t have as much interaction with other children during the pandemic, and when she started attending preschool in 2021, all the children wore face masks.

“She knows her numbers, she knows her ABCs, she knows how to spell her name,” Engram said. “But when she feels frustrated that she can’t do something, her frustration overtakes her. She needs extra attention and care. She has some shyness about her when she thinks she’s going to give the wrong answer.”

Socialization is not the only thing some children missed during the pandemic. Some families are also waiting to start public school because their children were not potty-trained during the pandemic, Lundy said. Bananas offers free diapers to low-income families, and staff have noticed the sizes requested getting bigger and bigger since Covid began.

Many reasons for opting out

Overall enrollment in California public schools has been steadily dropping for several years, in part due to a decrease in population and birth rate. But the drop in kindergarten enrollment of almost 40,000 children between 2019-20 and 2020-21 reflects other factors, researchers said.

“Kindergarten, and to a lesser extent first grade, are moving differently from other elementary grades,” said Julien Lafortune, research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. “It’s definitely something that’s not just the underlying demographics.”

The drop in 2020 was likely in large part due to kindergarten being online in most school districts.

“Asking a 4-year-old to sit in front of a computer for the whole day, it’s totally not what they need,” said Patricia Lozano, director of Early Edge California, a nonprofit organization that advocates for quality early learning. “If you know about child development, you try to avoid screens as much as possible. They need interactions. They need to play.”

When schools returned to in-person learning in 2021, there were many rules for children to follow to prevent the spread of Covid-19: masking, testing and keeping a safe distance from other students.

In addition, some families were concerned about the risk of their children getting Covid-19 in school or bringing it home to younger siblings, particularly before vaccines were available for young children.

Some families may have also moved out of California during the pandemic, in part because of rising housing costs in California coupled with the parents’ ability to work remotely, Lafortune said.

Districts trying to attract youngest students

Several district spokespersons said districts are trying to recruit more children to enroll in both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten, advertising on television, radio, and social media, and holding community events.

Since transitional kindergarten is gradually expanding to serve all 4-year-olds, districts are trying to leverage that expansion to enroll families early.

Their biggest challenge is continuing drops in kindergarten enrollment, reported by more than half of California’s nearly 1,000 districts between 2019-20 and 2021-22.

Districts contacted by EdSource say the decline continued into the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years.

Early learning grades should not be seen as optional in our community. They are essential in the life of young children.

Fresno Unified spokesperson A.J. Kato

Anaheim Elementary School District in Orange County has seen kindergarten enrollment fall year after year since the pandemic. The district’s data for 2023-24 shows a 22.7% drop from pre-pandemic levels, from 2,169 in 2019-20 to 1,676 this year.

The district’s drop in kindergarten enrollment started with Covid-19 and health concerns and expanded, said Mary Grace, assistant superintendent of education services in the district. “Anaheim and most Orange County school districts have experienced ongoing demographic changes and reduced birth rates that play a role in our enrollment numbers over the past few years.”

To stem the drop, Grace said the district is trying to attract more students to both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten with information sessions and an annual “enrollment festival” and advertising that the district offers dual-language immersion classes in Spanish, Korean and Mandarin at all 24 schools in the district, and transitional kindergarten at all schools.

Fresno Unified, which is the third-largest district in the state and also has the third-highest kindergarten enrollment, has seen more than a 16% drop in its kindergarten enrollment from 2019-20 to 2023-24, district data shows.

“The superintendent’s message to our community has been that early learning grades should not be seen as optional in our community. They are essential in the life of young children,” said district spokesperson A.J. Kato. “We are confident that with community outreach efforts and families feeling more comfortable sending their young children to school, we should see and continue increasing enrollment.”

Erica Peterson, the director of education and engagement for School Innovations & Achievement, a national firm that tracks attendance at 356 school districts in California, said school districts need to do more to attract families with young children post-pandemic.

“If we’re trying to stave off declining enrollment, what are we doing to entice people to choose their local home school?” said Peterson. “Because there are a lot of options and the pandemic created a whole wealth of options that didn’t even exist before,” she added, referring to homeschooling and private schools.

Where they went

It’s not completely clear what children did instead of kindergarten in the years since the pandemic. Lafortune said the numbers of students enrolled in private school and registered with the state as being in homeschools are not large enough to account for all of California’s missing kindergartners.

However, since kindergarten is not mandatory in California, parents and guardians are not required to register their children as enrolled in homeschool.

Children enrolled in private preschools or child care centers would not show up in the number of children enrolled in private K-12 schools. Preschools and child care programs are licensed separately by the Department of Social Services and do not have to register with the Department of Education as providing elementary school.

Lafortune said some parents may have chosen to skip kindergarten and then enroll their child in first grade the following year, but first grade has also seen drops in enrollment, so it is difficult to know how many kindergarteners enrolled. He said others may have chosen to wait a year to enroll their children in kindergarten, when they were 6 rather than 5 years old.

Some private preschools opened kindergarten-age classes during the pandemic to cater to families that preferred in-person

Nancy Lopez chose to keep her daughter Naima at a “forest” preschool, Escuelita del Bosque, which holds classes outside in a redwood forest park in the Oakland hills, in part because of the small class size. Kindergarten classes in Oakland can be up to 28 children with one adult. Escuelita del Bosque had a 10-to-1 ratio, with a kindergarten teacher who Lopez says was beloved by families. Naima is now enrolled in first grade at a public school.

“We just felt like there was nothing to lose from Naima being in this environment that’s more catered to this small group,” Lopez said. “It almost felt like we were gifted another year. It was almost pushing off the inevitable.”

EdSource data journalist Daniel J. Willis contributed to this story.

-

Advocacy group leader talks about the challenges of transitional kindergarten

Credit: Randall Benton / EdSource

Michael Olenick has spent his life pondering the preschool years. His mother, a childhood development professor, was one of the first Head Start teachers back in the 1960s, so he started preschool at age 3.

credit: CCRC

credit: CCRCIn some ways, he has never left that space. Olenick, a lifelong advocate for children and families and president of the Child Care Resource Center, a California-based advocacy organization, has long been a champion of early childhood education, having seen its power to uplift lives firsthand. But he worries that the educational system often pits the needs of one age group of children against another.

For instance, he worries that the rollout of transitional kindergarten, or TK, not only has undermined the preschool sector by stealing away some of its 4-year-olds. He also notes that TK is poised to run into a number of speed bumps ahead, including a lack of facilities and the need for more child developmental training, as it reaches full implementation in the fall.

Olenick, who received his Ph.D. from UCLA in educational psychology and has shaped the field with influential research on the importance of quality child care, recently made time to chat about his passion for early education and what he sees as the key challenges facing TK.

What fascinates you most about early ed?

My mother said that I always liked kids because I always had to be there in her classrooms. To me, it’s the most hopeful period of time, the opportunity to change kids’ trajectories the most. It’s the most hopeful time in life.

What are the biggest challenges in the expansion of TK? Do you worry about too much academic rigor, potty training incidents, the need for nap time?

All of those issues. In the ’80s I evaluated hundreds of preschool programs and kept running into large numbers that were drilling children on colors, numbers and letters for inordinate amounts of time. Boys had a harder time with this than girls. In looking at teacher qualifications, I saw lots of certificated teachers who were doing the drilling. I realize that’s a long time ago, but I keep hearing from colleagues seeing the same thing now. That’s why we pushed for early childhood education units for TK teachers. The other issue that comes up is many schools are designed for children to go to the bathroom unescorted. Four-year-olds can get lost there.

What do you think is the root source of the problem? A lack of understanding of child development, like the realities of potty training?

I don’t think most current teachers understand early development. Over time, this may right itself if they get the education they need. But principals have to have the expectation that TK is not first grade. Also, teachers do not generally handle toileting issues, and schools are not designed for 4-year-olds.

Is the academic pressure too high today?

I recently got an email from my first adviser at UCLA saying she went to half a dozen TK classrooms, and it looked like first grade. I wrote her back and I said, I told you so. We don’t have enough people yet that understand that kids learn differently. People learn at different rates, and we try to put them all into the same box and have them all learn stuff at the same time. Some of them are just not ready yet. You have to individualize instruction.

Why do you think the TK take-up rate has been more sluggish than expected?

Some of the biggest challenges are in rural districts, where they can’t get a very large number to attend, and the lack of child-sized facilities, especially easily accessible bathrooms. Also, I don’t buy the part about this helping all lower-income children because their parents need a full-day, full-year solution, not just three hours. For families who have a predictable schedule, a 9-to-5 job, TK with aftercare probably works pretty well, but some families need more flexibility.

Why are small ratios so important?

There has always been the rationale for safety. But more recent literature focuses on individual interactions between adults and children, and the fewer children per adult increases interactions, learning and attachment.

Why is play so key in TK?

Play is so important. I’ve heard from several TK program directors who said it took their administrators five years to recognize that play was learning. It’s not just the teachers that need to be trained on what’s developmentally appropriate; it’s important for principals, too. You know, a principal comes into a classroom and expects to see that teacher up in front of that class teaching. So if you go in and you see all these kids are playing, you may not realize they are being taught. It’s all about how you structure things in the classroom because you can get the same results in a play environment. You don’t have to drill kids.

Do you think we focus on setting a solid preschool foundation too much when financial stability may be more important for families?

It’s at least as important. We do a lot of work with families that are below the federal poverty line, the poorest of the poor. There are classrooms where there are kids who seem to be defiant. There was one kid who, it turns out, was deaf, and it took a long time to get him checked. He wasn’t being defiant; he just couldn’t read our lips. We have to work to give families what they need.

-

Transitional kindergarten comes of age in California

Students listen to their teacher during a transitional kindergarten class in Long Beach.

Credit: Lillian Mongeau/EdSource Today

Top Takeaways

- Transitional kindergarten, or TK, becomes available to all 4-year-olds in the fall.

- Smaller child-to-staff ratios, 10-to-1, are slated to start in the 2025-2026 school year.

- Early exposure to the basics of reading and math can kick-start academic achievement, experts say.

Paula Merrigan loves being a transitional kindergarten (TK) teacher so much she says she may never retire. She’d miss the wonder of a class filled with hugs, light bulb moments, and little ones who call her mom. She’d miss sitting cross-legged on the alphabet rug, hearing plans for a cat birthday party.

In teaching, a field often beset by burnout and high turnover, TK stands out as a joyous and messy world of puzzles, finger painting and puppet theater, a world unique from the rest of the K-12 system. This fall, California’s long-awaited vision of universal pre-kindergarten finally comes to fruition as transitional kindergarten, or TK, becomes accessible to all 4-year-olds across the state.

“I love working with this age,” said Merrigan, 57, a veteran teacher holding court in a classroom jam-packed with construction paper butterflies, hearts and Dr. Seuss characters. Merrigan has spent 17 years teaching kindergarten and transitional kindergarten in the Castro Valley Unified School District. “They’re so happy to come to school. They take genuine pleasure in learning. They enjoy it. They want to be here. They have a really good time, and so do I.”

Spearheaded by Gov. Gavin Newsom and Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, D-Sacramento, the roughly $3 billion program has been described by many experts as a game-changer for families in a state with about 2.6 million children under the age of 5. Many hope that increasing access to preschool may be one of the keys to closing the state’s ever-widening achievement gap. Given that about 90% of brain growth happens before kindergarten, perhaps it should come as little surprise that children who attend preschool are more likely to take honors classes and less likely to repeat a grade or drop out of school, research suggests.

“We know that early childhood experience strongly influences cognitive development and that many of the problems that become evident later in life, including high rates of failure, are set in motion before children enter kindergarten,” said W. Steven Barnett, the senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), which is based at Rutgers University. “We have strong causal evidence for links with educational attainment that has high payoffs over a lifetime.”

Four-year-old student, Alan, mimics the movements to a song about numbers during a kindergarten program at East Oakland Pride Elementary School. ASHLEY HOPKINSON/EDSOURCE TODAYOnce lagging behind the rest of the country in preschool access, some say California may now be poised to lead the way. The state now ranks 13th in the nation in preschool enrollment for 4-year-olds. That’s up from ranking 18th for 4-year-old access in 2023, according to a national NIEER report that ranks state-funded preschool programs.

“California’s TK is huge for the early childhood education field,” said Barnett. “The state is getting closer each year to achieving its goal of universal preschool for 4-year-olds.”

A stepping stone between preschool and kindergarten, TK began in 2012 as a program for “fall babies,” children who narrowly missed the cutoff date for kindergarten. Now it’s been expanded to function as a kind of universal pre-kindergarten initiative. Yet even as TK is set to become a real grade, just like any other K-12 grade, there are myriad challenges looming on the horizon, from finding qualified teachers amid a dire staffing shortage to how to ensure quality instruction and suitable facilities. Class size and specialized teacher training are among the major concerns.

California will need roughly 12,000 extra teachers and about 16,000 aides to keep the TK rollout on schedule, research suggests.

“More TK students means districts need more TK teachers,” said Gennie Gorback, an early childhood educator and president-elect of the California Kindergarten Association. “Because TK is a special grade that requires credentialed teachers to have additional early childhood education units, it’s more of a challenge to find qualified teachers.”

Candidates need a bachelor’s degree, must complete courses in child development or early childhood education, take the state’s teacher performance exam and log 600 hours in the classroom. Without pay. Those requirements may be holding back preschool teachers, who already teach 4-year-olds, from taking better-paying TK jobs, experts say.

“We feel from a position of equity and respect for the experience of preschool teachers that the current pathways are still inadequate,” said Anna Powell, senior research and policy associate at Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE). “If 4-year-olds are moving into TK, some of their highly skilled teachers should have a streamlined pathway to go with them.”

Quality also remains a key issue. The NIEER report scored California’s TK program a mere 3 out of 10 criteria, largely for having a crowded class size of 24 children in a classroom and an average 12-to-1 student-to-staff ratio. Teacher training is also a factor.

“Building quality is job one for the future,” said Barnett. “Providing guidance and continuous improvement so that TK develops as a program appropriate for 4-year-olds.”

Newsom’s latest 2025-26 budget sets aside $1.2 billion to add new students and also help reduce TK staff ratios to 10-to-1, slated to start in the 2025-2026 school year.

“Low spending results in low quality,” according to the report. “While that may seem to save money, it is wasteful and costly in the long run to fund programs that do not adequately support long-term gains and may even harm long-term outcomes for some children.”

Paula Merrigan Small class sizes are critical, experts say. For the record, the gold standard for the early education sphere is more like 8-to-1, like the state’s public preschool program, which met six out of 10 benchmarks.

“The real key is a small ratio,” said Gorback. “Having more adults in the room helps ensure that each child gets the attention and guidance they need.”

Play is the heart of learning at this age. Merrigan’s classroom encourages guided play that enhances learning, such as math games students beg to play and a kinetic sandbox that sparks creativity and motor skills.

“I love to watch the aha moments,” said Merrigan, who tested out many activities on her own son to see if they were fun as well as edifying. “I love seeing kids who come in knowing no letters and no numbers, and they leave knowing every letter and every sound. It’s amazing. And we do it all through play.”

Another roadblock is that some school districts don’t have enough space and facilities for TK classrooms or the resources to add everything from potties to playground equipment sized for 4-year-olds. Some Oakland schools, for instance, don’t have any TK classrooms, which is why some children end up on wait lists for their preferred school.

“Space is an incredible challenge for schools,” said Gorback. “Most elementary schools were not built with TK classrooms in mind, so administrators are having to get creative in making sure that all of their young learners have the space they need.”

After declining during the pandemic, TK growth has been accelerating. Enrollment jumped by more than 35,000 children from the previous school year, according to Bruce Fuller, professor of education and public policy at UC Berkeley, now standing at roughly 151,000, but the rub is that the bump in TK enrollment may have come at the expense of other programs. Some families simply switched from one program to another.

“Enrollments in center-based programs have stalled overall,” Fuller said.

Certainly, ushering in a new grade at a time of profound upheaval, from learning loss to chronic absenteeism in the school system, may be an unwieldy challenge, experts say, but it also should be noted that early education can have the greatest impact now, even as the youngest learners struggle to recover from the damage caused by pandemic-era school closures.

“TK absolutely can help with pandemic recovery and with changes that we see in children’s development that persist,” added Barnett, “but this will require focused attention to ensure good practice, ensure children with the greatest needs enroll, and ensure high attendance rates when they do enroll.”