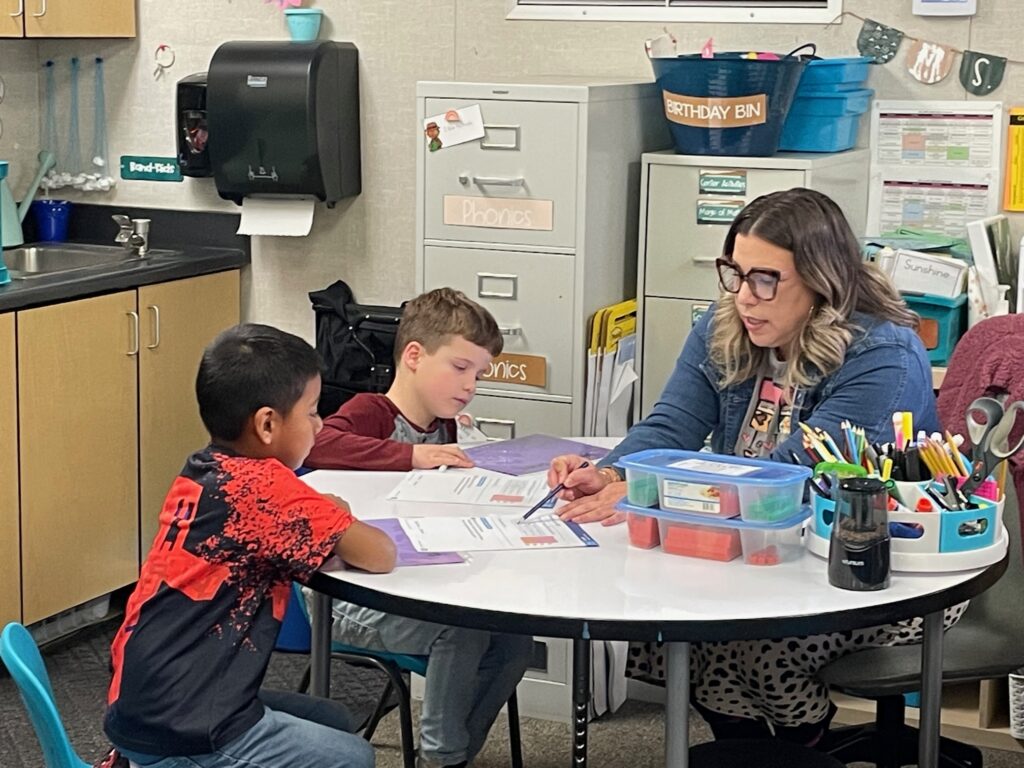

Teacher apprentice Ja’net Williams helps with a math lesson in a first grade class at Delta Elementary Charter School in Clarksburg, near Sacramento.

Credit: Diana Lambert / EdSource

Top Takeaways

- California leaders dismiss the criticism and methodology of the rankings.

- And yet, graduate credentialing programs cram a lot in a year.

- Many teachers may struggle with the demands of California’s new math framework.

In its “State of the States” report on math instruction published last week, the National Council on Teacher Quality sharply criticized California and many of its teacher certification programs for ineffectively preparing new elementary teachers to teach math and for failing to support and guide them once they reach the classroom.

“Far too many elementary teacher prep programs fail to dedicate enough instructional time to building aspiring teachers’ math knowledge — leaving teachers unprepared and students underserved,” the council said in its evaluation of California’s 87 programs that prepare elementary school teachers. “The analysis shows California programs perform among the lowest in the country.”

The report’s call for more teacher math training and ongoing support coincides with the state’s adoption this summer of materials and textbooks for a new math framework that math professionals universally agree will be a heavy lift for incoming and veteran teachers to master. It will challenge elementary teachers with a poor grasp of the underpinnings behind the math they’ll be teaching.

Kyndall Brown, executive director of the California Mathematics Project based at UCLA, agrees. “It’s not just about knowing the content, it’s about helping students learn the content, which are two completely different things,” he said.

And that raises a question: Does a one-year-plus-summer graduate program, which most prospective teachers take, cram too much in a short time to realistically meet the needs to teach elementary school math?

Failing grades

The council graded every teacher prep program nationwide from A to F, based on how many instructional hours they required prospective teachers to take in major content areas of math and in instructional methods and strategies.

Three out of four California programs got an F, with some programs — California State University, Sacramento, and California State University, Monterey Bay — requiring no instructional hours for algebraic thinking, geometry, and probability, and many offering one-quarter of the 135 instructional hours needed for an A.

But there was a dichotomy: All the Fs were given to one-year graduate school programs offering a multi-subject credential to teach elementary school, historically the way most new teachers in California get their teaching credential.

On the other hand, many of the colleges and universities offering a teaching credential and a bachelor’s degree through an Integrated Undergraduate Teacher Credentialing Program got an A, because they included enough time to go into math instruction and content in more depth. For example, California State University, Long Beach’s 226 instructional hours, apportioned through all of the content areas and methods courses, earned an A-plus.

The California State University rejects the recent grading from the National Council on Teacher Quality about our high-quality teacher training programs

California State University

Most of the universities that offer both undergraduate and graduate programs — California State University, Bakersfield; San Jose State University; California State University, Chico; California State University, Northridge, to name a few — had the same split: A for their undergraduate programs, F for their graduate credentialing programs.

Most California teacher preparation programs have received bad grades in the dozen years that the council has issued evaluations. The state’s higher education institutions, in turn, have defended their programs and denounced the council for basing the quality of a program on analyses of program websites and syllabi.

California State University, whose campuses train the majority of teachers, and the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, which accredits and oversees teacher prep programs, issued similar denunciations last week.

“The California State University rejects the recent grading from the National Council on Teacher Quality about our high-quality teacher training programs,” the CSU wrote in a statement. The council “relies on a narrow and flawed methodology, heavily dependent on document reviews, rather than on dialogue with program faculty, students and employers or a systematic review of meaningful program outcomes.”

The credentialing commission, in a more diplomatic response, agreed. The report “reflects a methodology that differs from California’s approach to educator preparation,” it said. “While informative, it does not fully capture the structure of California’s clinically rich, performance-based system.”

Heather Peske, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality for the past three years, dismissed the criticism as “a really weak critique.”

“You can look at a syllabus and see what’s being taught in that class much in the same way that if you go to a restaurant and look at the menu to see what’s being served,” she said. “Our reviews are certainly a very solid starting place to know to what extent teacher preparation programs are well preparing future teachers to be effective in teaching.”

It’s not just a problem in California.

“When we compare the mathematics instructional hours between the undergrad and the graduate programs, often on the same campus, we saw on average that undergrads get 133 hours compared to just 52 hours at the graduate level. In both cases, it is not meeting the recommended and research-based 150 hours,” Peske said.

Part of the problem is that graduate programs usually don’t have enough time to instill future teachers with the content knowledge that they need.

Heather Peske

Whether or not examining website data is a good methodology, the disparities in hours devoted to math preparation between undergraduate and graduate programs raise an important issue.

True jacks of all trades, elementary teachers must become proficient in many content areas — social studies, English language arts, English language development for English learners, and science, as well as math. Add to that proficiency in emerging technologies, classroom management, skills for teaching students with disabilities, and student mental health: How can they adequately cover math, especially?

“Part of the problem is that graduate programs usually don’t have enough time to instill future teachers with the content knowledge that they need,” Peske said. “California programs have to reckon with this idea that they’re sending a bunch of teachers into classrooms who have not demonstrated that they are ready to teach kids math.”

Brown said, “There’s no way that in a one-year credential program that they’re going to get the math that they need to be able to teach the content that they’re responsible for teaching.”

That was Anthony Caston’s experience. Before starting his career as a sixth-grade teacher at Foulks Ranch Elementary School in Elk Grove three years ago, Caston took courses for his credential in graduate programs at Sacramento State and the University of the Pacific. There wasn’t enough time to learn all he needed to teach the subject, he said. A few classes were useful, but didn’t get much beyond the third- or fourth-grade curriculum, he said.

“I had to take myself back to school, reteach myself everything, and then come up with some teaching strategies,” Caston said.

Fortunately for him, veteran teachers at his school helped him learn more about Common Core math and how to teach it.

The math content Brown refers to goes beyond knowing how to invert fractions or calculate the area of a triangle; it involves a conceptual understanding of essential math topics, Peske said. Only a deeper conceptual grasp will enable teachers to diagnose and explain students’ errors and misunderstandings, Peske said, and to overcome the math phobia that surveys show many teachers have.

Ma Bernadette Salgarino, the president of the California Mathematics Council and a math trainer in the Santa Clara County Office of Education, acknowledges that many math teachers have not been taught the concepts behind the progression of the state’s math standards. “It is not clear to them,” she said. “They’re still teaching to a regurgitation of procedures, copy and paste. These are the steps, and this is what you will do.”

Although a longtime critic of the council, Linda Darling-Hammond, who chaired California’s credentialing commission before becoming the current president of the State Board of Education, acknowledges that the report raises a legitimate issue.

“Time is an important question,” she said. “It is true that having more time well spent — the ‘well spent’ matters — could make a difference for lots of people in learning lots of subjects, including math.”

Darling-Hammond faults the study, however, for not factoring in California’s broader approach to teacher preparation, including requiring that teaching candidates pass a performance assessment in math and underwriting teacher residency programs, in which teachers work side by side with an effective teacher for a full year while taking courses in a graduate program.

“You could end up becoming a pretty spectacular math teacher in a shorter amount of time than if you’re just studying things in an undergraduate program disconnected from student teaching,” she said.

Weak state policies

The report also grades every state’s policies on math instruction, from preparing teachers to coaching them after they’re in the classroom. California and two dozen states are rated “weak,” ahead of seven “unacceptable” states (Montana, Arizona, Nebraska, Missouri, Alaska, Vermont and Maine) while behind 17 “moderate” states, including Texas and Florida, and a sole “strong” state, Alabama.

The council bases the rating on the implementation of five policy “levers” to ensure “rigorous standards-aligned math instruction.” However, California’s actions are more nuanced than perhaps its “unacceptable” ratings on three and “strong” ratings on two would indicate.

For example, the council dinged the state for not requiring that all teachers in a prep program pass a math licensure test. California does require elementary credential candidates to pass the California Subject Examinations for Teachers, or CSET, a basic skills test, before they can teach students. But the math portion is combined with science, and students can avoid the test by supplying proof they have taken undergraduate math courses.

At the same time, many superintendents and math teachers may be doing a double-take for a “strong” rating for providing professional learning and ongoing support for teachers to sustain effective math instruction.

Going back to the adoption of the Common Core, the state has not funded statewide teacher training in math standards. In the past five years, the state has spent $500 million to train literacy coaches in the state’s poorest schools, but nothing of that magnitude for math coaches.

The Legislature approved $20 million for the California Mathematics Project for training in the new math framework, which was passed in 2023, and $50 million in 2022-23 for instruction in grades fourth to 12th in science, math and computer science training to train coaches and teacher leaders — amounts that would be impressive for smaller states, but not to fund training most math teachers in California. (You can find a listing of organizations offering training and resources on the math framework here.)

In keeping with local control, Gov. Gavin Newsom has appropriated more than $10 billion in education block grants, including the Student Support and Professional Development Discretionary Block Grant, and the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant, but those are discretionary; districts have wide latitude to spend money however they want on any subject.

Tucked into a section on Literacy Instruction in Newsom’s May budget revision (see Page 19) is the mention that a $545 million grant for materials instruction will include a new opportunity to support math coaches, too. The release of the final state budget for 2025-26 later this month will reveal whether that money survives.

Brown calls for hiring more math specialists for schools and for three-week summer intensive math leadership institutes like the one he attended in 1994. It hasn’t been held since the money ran dry in the early 2000s.

EdSource reporter Diana Lambert contributed to this article.