Credit: Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages

A few weeks ago, my high school chemistry class sat through an “AI training.” We were told it would teach us how to use ChatGPT responsibly. We worked on worksheets with questions like, “When is it permissible to use ChatGPT on written homework?” and “How can AI support and not replace your thinking?” Another asked, “What are the risks of relying too heavily on ChatGPT?”

Most of us just used ChatGPT to finish the worksheet. Then we moved on to other things.

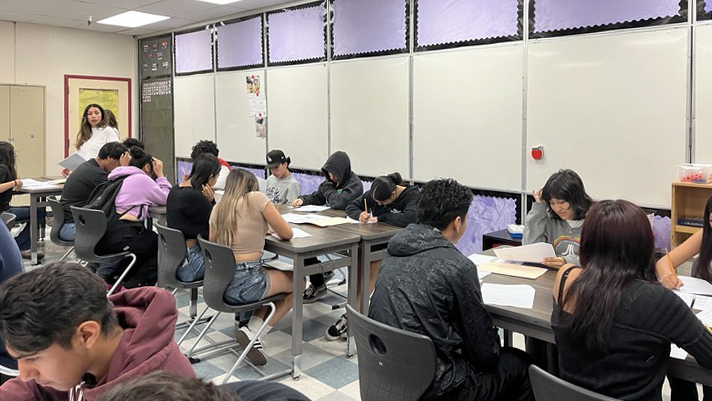

Schools have rushed to regulate AI based on a hopeful fiction: that students are curious, self-directed learners who’ll use technology responsibly if given the right guardrails. But most students don’t use AI to brainstorm or refine ideas — they use it to get assignments done faster. And school policies, built on optimism rather than observation, have done little to stop it.

Like many districts across the country, our school policy calls students to use ChatGPT to brainstorm, organize, and even generate ideas — but not to write. If we use generative AI to write the actual content of an assignment, we’re supposed to get a zero.

In practice, that line is meaningless. Later, I spoke to my chemistry teacher, who confided that she’d started checking Google Docs histories of papers she’d assigned and found that huge chunks of student writing were being pasted in. That is, AI-generated slop, dropped all at once with no edits, no revisions and no sign of actual real work. “It’s just disappointing,” she said. “There’s nothing I can do.”

In Bible class, students quoted ChatGPT outputs verbatim during presentations. One student projected a slide listing the Minor Prophets alongside the sentence: “Would you like me to format this into a table for you?” Another spoke confidently about the “post-exilic” period— having earlier that week mispronounced “patriarchy.” At one point, Mr. Knoxville paused during a slide and asked, “Why does it say BCE?” Then, chuckling, answered his own question: “Because it’s ChatGPT using secular language.” Everyone laughed and moved on.

It’s safe to say that in reality, most students aren’t using AI to deepen their learning. They’re using it to get around the learning process altogether. And the real frustration isn’t just that students are cutting corners, but that schools still pretend they aren’t.

That doesn’t mean AI should be banned. I’m not an AI alarmist. There’s enormous potential for smart, controlled integration of these tools into the classroom. But handing students unrestricted access with little oversight is undermining the core purpose of school.

This isn’t just a high school problem. At CSU, administrators have doubled down on AI integration with the same blind optimism: assuming students will use these tools responsibly. But widespread adoption doesn’t equal responsible use. A recent study from the National Education Association found that 72% of high school students use AI to complete assignments without really understanding the material.

“AI didn’t corrupt deep learning,” said Tiffany Noel, education researcher and professor at SUNY Buffalo. “It revealed that many assignments were never asking for critical thinking in the first place. Just performance. AI is just the faster actor; the problem is the script.”

Exactly. AI didn’t ruin education; it exposed what was already broken. Students are responding to the incentives the education system has given them. We’re taught that grades matter more than understanding. So if there’s an easy shortcut, why wouldn’t we take it?

This also penalizes students who don’t cheat. They spend an hour struggling through an assignment another student finishes in three minutes with a chatbot and a text humanizer. Both get the same grade. It’s discouraging and painfully absurd.

Of course, this is nothing new. Students have always found ways to lessen their workload, like copying homework, sharing answers and peeking during tests. But this is different because it’s a technology that should help schools — and under the current paradigm, it isn’t. This leaves schools vulnerable to misuse and students unrewarded for doing things the right way.

What to do, then?

Start by admitting the obvious: if an assignment is done at home, it will likely involve AI. If students have internet access in class, they’ll use it there, too. Teachers can’t stop this: they see phones under desks and tabs flipped the second their backs are turned. Teachers simply can’t police 30 screens at once, and most won’t try. Nor should they have to.

We need hard rules and clearer boundaries. AI should never be used to do a student’s actual academic work — just as calculators aren’t allowed on multiplication drills or Grammarly isn’t accepted on spelling tests. School is where you learn the skill, not where you offload it.

AI is built to answer prompts. So is homework. Of course students are cheating. The only solution is to make cheating structurally impossible. That means returning to basics: pen-and-paper essays, in-class writing, oral defenses, live problem-solving, source-based analysis where each citation is annotated, explained and verified. If an AI can do an assignment in five seconds, it was probably never a good assignment in the first place.

But that doesn’t mean AI has no place. It just means we put it where it belongs: behind the desk, not in it. Let it help teachers grade quizzes. Let it assist students with practice problems, or serve as a Socratic tutor that asks questions instead of answering them. Generative AI should be treated as a useful aid after mastery, not a replacement for learning.

Students are not idealized learners. They are strategic, social, overstretched, and deeply attuned to what the system rewards. Such is the reality of our education system, and the only way forward is to build policies around how students actually behave, not how educators wish they would.

Until that happens, AI will keep writing our essays. And our teachers will keep grading them.

•••

William Liang is a high school student and education journalist living in San Jose, California.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.