A Cease Fire Now sign hangs on a tent on the grass as tents are set up in The Quad during a Students for Gaza rally at San Francisco State University on April 29, 2024.

Credit: Lea Suzuki/San Francisco Chronicle via AP

San Francisco State has pulled investments from three companies it says don’t meet its human rights standards following pressure from pro-Palestinian student activists.

The moves resulted in changes to the university’s $163 million investment portfolio.

SF State Foundation confirmed Wednesday that it has sold its Lockheed Martin corporate bond position and stock positions in Leonardo, an Italian multinational defense company, and Palantir Technologies, a U.S.-based data analysis firm that has worked with the Israeli Defense Ministry.

The foundation also screened out a fourth company, the construction equipment manufacturer Caterpillar, based on a pre-existing policy that steers the foundation away from investments in fossil fuels. The company has become a target of groups advocating divestment from Israel. They claim Caterpillar’s heavy equipment has been turned into weapons by Israel in the Palestinian territory.

College students around the country have pushed universities to remove companies aligned with Israel from investment portfolios. Student activists have met resistance from California State University system officials, who have said they won’t tinker with investment policies in reaction to the Israel-Hamas conflict. Instead, students on some campuses have focused their energy on school-level foundation endowments, but say their goal remains to influence the entire system’s investment policies.

San Francisco State students made headway by training their attention on the university foundation’s investment screens, standards used to make sure investments are consistent with the school’s values, like racial justice, social justice and climate change. The SF State Foundation shed investments in the four companies as the result of implementing those screens and not because it agreed to sell specific companies.

The changes come following a summer of Zoom meetings held by a work group composed of representatives from Students for Gaza, SF State Foundation investment committee, faculty and administrators.

The work group proposed a revised investment policy that says the foundation will not invest in arms makers and will “strive not to invest in companies that consistently, knowingly and directly facilitate or enable severe violations of international law and human rights.” The draft does not name any specific country or conflict.

The proposed policy is slated for a final vote in December. The foundation’s investment committee decided to act on the suggested revisions in the meantime, identifying the investments in Lockheed Martin, Leonardo and Palantir under the human rights screens.

The foundation also will unveil a new website disclosing more information about its endowment by the end of September.

“Through the work of the many students involved in GUPS (General Union of Palestine Students) at SFSU and SFG (Students for Gaza), we have been able to successfully ensure our money is not funding GENOCIDE ‼️” an Aug. 27 announcement on Instagram by the group Students for Gaza at San Francisco State said.

Sheldon Gen, a faculty representative to the SF State Foundation, said the work group landed on draft policy language that aligns the university’s investment policies with its values, without singling out a specific conflict, country or geographic area.

“What we did at San Francisco State isn’t going to end the conflict in Gaza, but we did find some space where students can have agency and be heard ― and not only that, but really, honestly improve our university,” he said.

Jeff Jackanicz, the president of the SF State Foundation, thanked students who participated in the work group in an Aug. 22 email to the campus outlining proposed changes to the foundation’s environmental, social and governance, or ESG, strategies.

“We have been lauded for being a leader in ESG investment before, and with credit to Students for Gaza, our revised policy affirms our leading role in values-driven advising,” Jackanicz wrote.

Students for Gaza scheduled a rally and news conference Thursday at 12:15 p.m. in San Francisco State’s Malcolm X Plaza to announce the investment changes.

A ‘tangible’ bid for divestment

The decision to tighten investment screens at San Francisco State follows a wave of campus protests calling on Israel to end an assault on Gaza that has killed more than 40,000 people, according to the local health ministry. The current fighting started on Oct. 7 when Hamas and other militants attacked Israel, killing more than 1,000 people and abducting hundreds more.

Rama Ali Kased, an associate professor of race and resistance studies and an adviser to students in the work group, said some on her campus were surprised to learn the university had any investments in arms makers. Asking the university to cut ties with those firms was “tangible and understandable,” she said — which made the case to drop those investments easier.

The SF State Foundation is the auxiliary organization responsible for raising private funding for the university and managing the university’s endowment, money the university funnels into facilities, scholarships and other university programs.

The foundation’s endowment spent $8.9 million of its income across the university in the 2022-23 fiscal year, according to Cal State records, and ranked as the seventh-largest in the Cal State system by market value.

This is not the first time that SF State has revised its foundation investment criteria following feedback from student activists. In 2013, the foundation limited direct investments in coal and tar sands, a step Cal State says was a first among U.S. public universities.

Each of the 23 campuses in the California State University system, as well as the Chancellor’s Office, has a separate endowment managed by an auxiliary organization. Together, the CSU endowments had a market value of $2.5 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year, growing roughly 8.7% year-over-year.

The Chancellor’s Office on April 30 released a statement saying that Cal State “does not intend to alter existing investment policies related to Israel or the Israel-Hamas conflict” because such divestment “impinges on the academic freedom of our students and faculty and the unfettered exchange of ideas on our campuses.”

Campus leaders nonetheless have some flexibility to manage their own endowments.

Sacramento State on May 8 announced new investment policy language as a concession to pro-Palestinian student groups. That language does not mention Israel specifically but instead directs the school’s foundation “to investigate socially responsible investment strategies which include not having direct investments in corporations and funds that profit from genocide, ethnic cleansing, and activities that violate fundamental human rights.”

Less than a week after the Sacramento State announcement, SF State agreed to revise its investment policies in consultation with student encampment representatives, setting in motion this summer’s work group.

But an incident at another Cal State campus suggests there are limits to how much leeway campus leaders have to negotiate with student protesters.

Mike Lee, then-president of Sonoma State University, announced on May 14 that he had reached an accord with protesters to review the school foundation’s investments and form an advisory council that would include a local chapter of the group Students for Justice in Palestine.

Lee was forced to backpedal soon afterward. The CSU placed him on administrative leave the following day, saying he announced the agreement without proper approvals. Lee decided to go back into retirement soon afterward.

The path to a deal

To Lynn Mahoney, the president of San Francisco State University, the student encampment pitched on her campus for roughly two weeks this spring had roots in a range of student concerns, from dizzying Bay Area housing costs to the climate change crisis.

“If these young people aren’t angry, they’re not paying attention,” Mahoney said.

That perspective shaped the way Mahoney responded when students organized protests in April. Mahoney agreed to participate in an open bargaining session held in the school’s Malcolm X Plaza, fielding questions from students and sharing information about the university’s investment practices.

“I just strongly urge presidents: Approach the students with respect, even if they’re out there hollering horrible things about you,” she said. “Approach them with respect. They’re your students.”

Kased said that by meeting with students at the encampment this spring, Mahoney and student protest leaders set a tone that allowed for the work group to continue over the summer.

“That move provided a space for students to feel empowered, but to say, ‘Look, we may not agree with President Mahoney on everything, but we’re going to sit down,’” Kased said.

The summer’s work group also benefited from a governance structure students developed during the spring encampment, Kased said, when students elected leaders to represent them and similarly identified faculty to act as spokespeople and liaisons in negotiations with the administration.

People who attended the meetings said they tended to be collegial rather than confrontational, and that rare moments of tension between students and campus officials were quickly quelled.

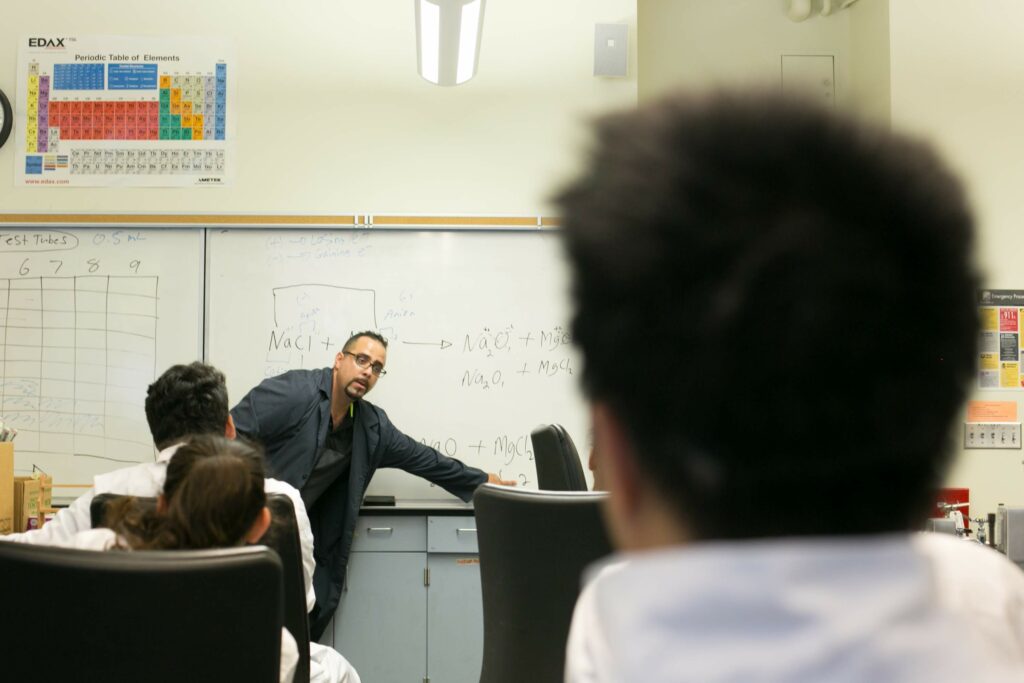

“These were tough discussions,” Gen said. “It’s the kind of discussion that professors aspire to have with their students in classes, quite honestly — challenging ones, where they raise tough questions, explore implications of perspectives and, most importantly, find some route for agency.”

Gen said the discussions with students this summer echoed previous debates within the foundation’s investment committee regarding whether to divest from specific countries due to their records on human rights. The committee has avoided naming specific countries in its policies, he said, instead articulating values its investments should reflect.

“We have a diversity of students who are on all sides of this specific issue here, too, and we weren’t going to alienate one student group for another,” he said. “They’re all our students.”

‘Not about money’

Some foundation investments are easier to screen than others.

Noam Perry, who works with activists leading divestment campaigns as part of his role at the American Friends Service Committee, acted as a de facto translator between San Francisco State students and university officials this summer.

He said one place where the work group made progress was by identifying specific investments held in separately managed accounts, an investment vehicle tailored to the university.

A foundation document dated Aug. 14 says the foundation will screen out “any company deriving more [than] 5% of revenue from weapons manufacturing, involved in the private prison industry, or engaging in detention at borders” from separately managed accounts.

But it can be harder to get a clear picture of other investment vehicles. Perry said that the foundation works with some asset managers that apply quantitative investment strategies. That means the manager buys and sells stocks dynamically — and the stock holdings change every day.

“That’s where conversations became really tense,” said Perry. “Because from the students’ perspective … this is unacceptable, because there’s no way that this vendor could ever be aligned with the responsible investment policy that the university is seeking. And from the university’s perspective, that’s where there’s revenue to be lost. They never said they had zero tolerance for having these companies. It’s always about minimizing exposure and reducing the risk that they’re invested in these (companies).”

Perry said how the foundation should handle such investments in the future remains an open question.

Jackanicz’s Aug. 22 email to the campus said the university’s “commingled investment strategies already align strongly with core environmental, social and governance (ESG) values.” He said the foundation believes “we can engage with fund managers over time to discuss changes that could have further positive impacts.”