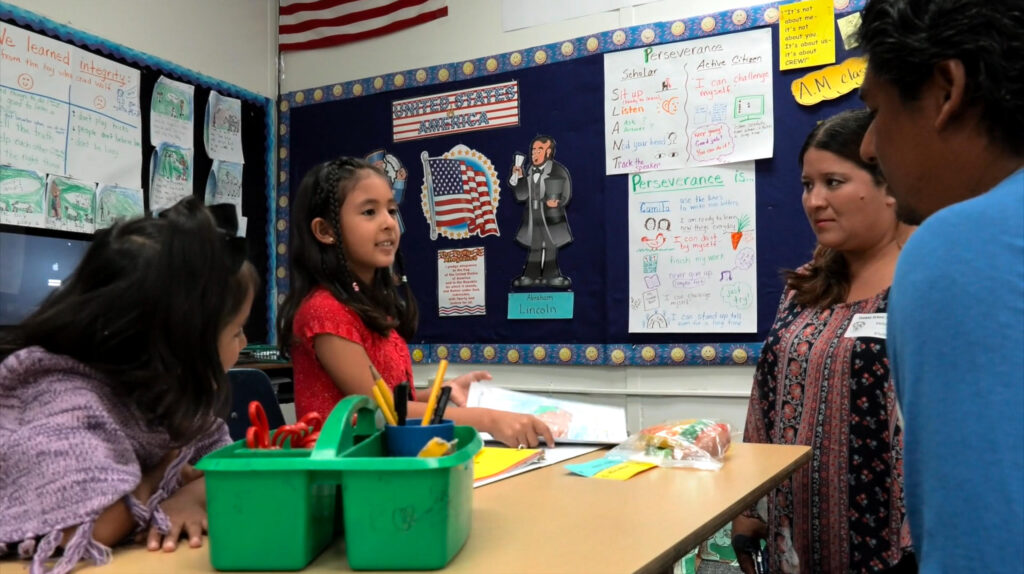

Kindergarten students at

in Robin Bryant’s class at West Contra Costa Unified’s Stege Elementary School are learning how to add and subtract.

Photo: Andrew Reed/EdSource

This story was updated on Nov. 15 to correct information received from a source.

Most exams to prove teachers are prepared to teach reading are ineffective, according to an analysis released Tuesday by the National Council on Teacher Quality. Only six of the 25 licensure tests currently used in the U.S. are considered to be strong assessments, including the Reading Instruction Competence Assessment, which California will do away with in 2025.

Fifteen of the 25 reading licensure tests being used in the U.S. were “weak” and four were “acceptable,” according to the analysis. One state does not require a reading licensure test.

Council researchers based their rankings on whether the licensure exam adequately addresses the five core components of the science of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. They also took into consideration whether the tests combined reading with other subjects and tested teachers on methods of reading instruction already debunked by researchers.

“The science of reading or scientifically-based reading instruction is reading instruction that’s been informed by decades of research on the brain and research on how people and how children learn to read,” said Heather Peske, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, a nonpartisan research and policy organization.

California will replace the Reading Instruction Competence Assessment, or RICA, with a literacy performance assessment that allows teachers to demonstrate their competence by submitting evidence of their instructional practice through video clips and written reflections on their practice.

“The state really needs to ensure that this new assessment is aligned to the science of reading and can provide an accurate and reliable signal that teachers have the necessary knowledge and skills to teach reading effectively,” Peske told EdSource.

The RICA addresses more than 75% of the topics in each of the five components of the science of reading. The state also gained points for not combining reading and other subjects in the examination, according to the analysis.

In California, the reading instruction assessment is required of teacher candidates seeking a multiple-subject, a prekindergarten to third grade early childhood education or an education specialist credential.

The RICA has not been popular in California in recent years. Critics have said it does not align with current state English language arts standards, is racially biased and has added to the state’s teacher shortage.

Between 2017 and 2021, more than 40% of teachers failed the test the first time they took it, according to state data. Black and Latino teacher candidates overall have lower passing rates on the test than their white and Asian peers.

“I think that when you have a test that is aligned to the research like the RICA and … a third of candidates are failing, it signals that they’re not getting the preparation aligned to the assessment, aligned to what’s on the test,” Peske said.

Low student test scores nationwide have most states reconsidering how they teach literacy. Fewer than half of students who took the California Smarter Balanced Tests met or exceeded state standards in English language arts in 2023.

California Senate Bill 488, passed in 2021, called for new literacy standards and a teacher performance assessment that emphasized teaching foundational reading skills that include phonological awareness, phonics and word recognition, and fluency. The new standards also included support for struggling readers, English learners and pupils with exceptional needs. The California Dyslexia Guidelines have been incorporated for the first time.

The California literacy performance assessment that will replace the RICA on July 1, 2025, is based on new literacy standards and teaching performance expectations approved by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing last year. The standards and teaching expectations are derived from state literacy policies and guidance, including the state’s English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework and the California Comprehensive State Literacy Plan.

The performance assessment was designed by a team of teachers, professors, researchers, nonprofit education advocacy organizations and school district administrators. It will be piloted in next spring, said Nancy Brynelson, statewide literacy co-director at the California Department of Education, who serves as a liaison to the assessment design team.

“There was a view that a performance assessment would do a better job of showing what a teacher can really do, how a teacher can apply their knowledge about literacy to a classroom situation and to particular students who need support,” Brynelson said. “And there had been a call for changing that test for quite a while.”

The assessment will be revised in the summer and field-tested with a larger number of teacher preparation programs in the 2024-25 school year, said Mary Vixie Sandy, executive director of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing.

“High-stakes standardized tests evaluate whether prospective teachers know enough about a subject, while performance assessments measure whether students can apply the knowledge appropriately in various contexts,” Sandy said. “As such, performance assessments serve to strengthen and deepen a prospective teacher’s knowledge and skill based on authentic practice in real classrooms.”