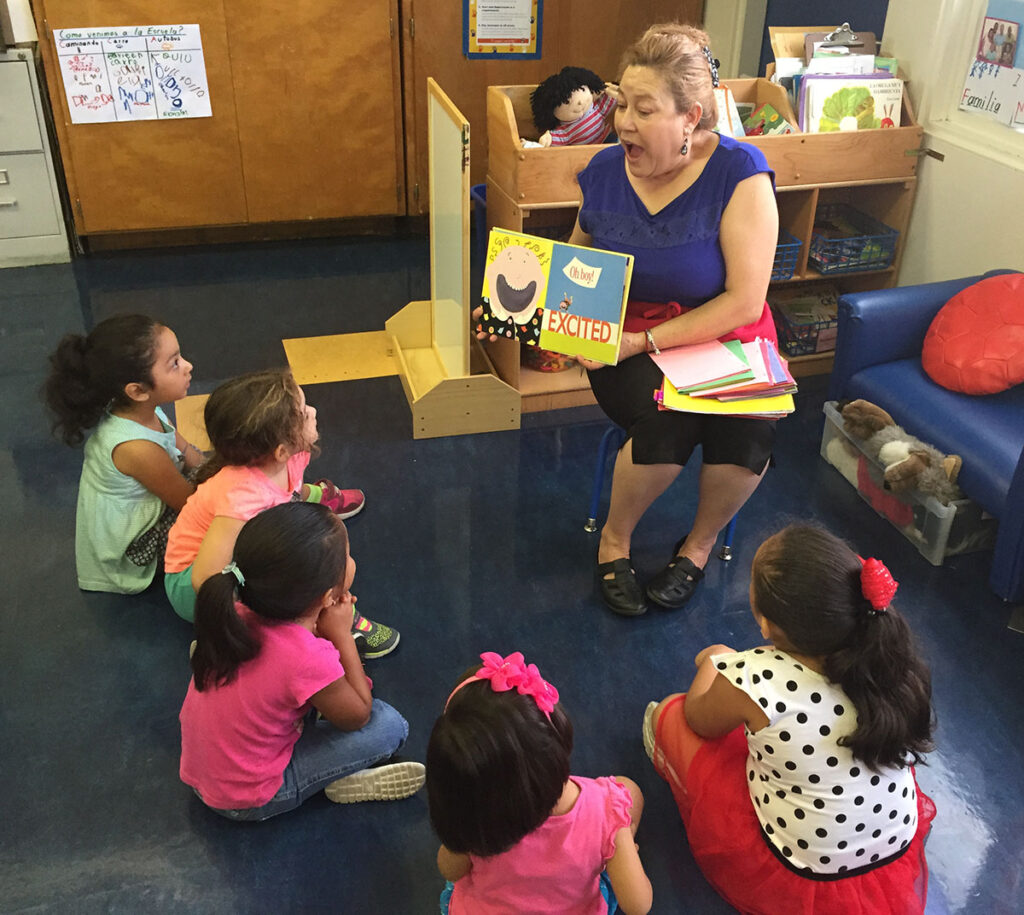

Credit: Alison Yin / EdSource

Students in precarious living situations — especially foster and homeless youth —are much more likely to be suspended and lose instructional time vital to their academic success, according to a report released by the UCLA Civil Rights Project and the National Center for Youth Law.

In the 2021-2022 academic year alone, California students lost more than 500,000 days to out-of-school suspensions, where students are sent home as a form of discipline, the study said.

Across the state, foster youth were disproportionately at the receiving end of the punishment, and they lost more time than “all students” across the board to suspensions — about 77 days of instruction for every 100 students.

Specifically, for every 100 African American foster youth enrolled, 121 days were lost while, African American homeless youth lost 69 days of instruction, according to the report which was released Oct. 30. Meanwhile, homeless students overall missed 26 days per 100 students.

Regardless of whether they are in foster care, students with disabilities lost 23.8 school days per 100, a rate higher than the general population. Dan Losen, senior director for the National Center for Youth Law and co-author of the report, said that missing a day of instruction could result in loss of these students’ access to disability-specific supports, such as counseling.

“A regular day might be one of the most important days of the week for the students with disabilities,” Losen said. “So, in some sense, they’re getting a harsher punishment and being denied more.”

Challenges for foster youth and homeless students

K-12 students across the state have already lost a lot of ground academically since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; Losen said that missing even more days to suspensions is detrimental.

Losing instructional time “is harming their educational outcomes, not just in the immediate, but it makes it less likely they’re ever going to graduate,” Losen said. “It puts their academic and personal futures at greater risk.”

According to the report, suspending a student — even once — is associated with diminished chances of graduating from high school and attending college, as well as an increased probability of being arrested later in life.

Losen added that suspensions are more likely to cause delinquent behavior than curb it.

“Suspending a student out of school is really a non-intervention. It’s no guarantee that anything will happen. They’re just going to come back to school three days or two days later,” Losen said.

“Not that you should put up with misconduct, but there’s got to be a way to support these kids, especially those from these unstable home environments.”

To make matters worse, these students who are being disproportionately suspended are already likely to have experienced trauma outside of school, Losen said.

“The more (adverse experiences) you have, the more likely it is you’ll have a form of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and that definitely affects behavior. … Some of them might withdraw into a shell, but others might act out in ways that they might normally not act out,” Losen said.

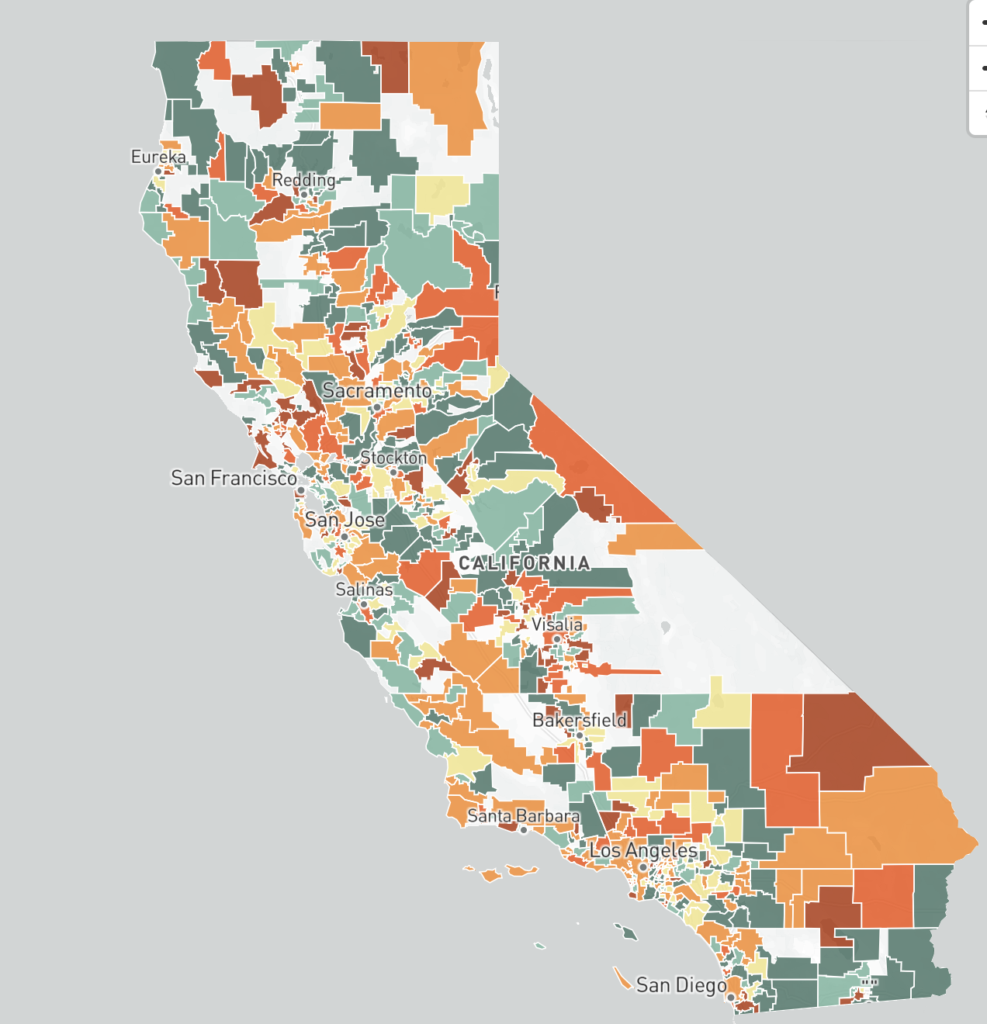

Discrepancies across districts

The report shows records varied from district to district — from Kern High School District where 23.3 days of instruction have been lost per 100 students to Los Angeles Unified School District, where only 0.7 days of instruction per 100 students were lost.

“Racial biases (in student discipline) are prevalent, and they don’t have to be intentional,” said Losen, noting that homeless and foster youth are disproportionately Black and brown.

That implicit bias “means you’re not aware of how you may be biased in not just how you punish, but who you’re looking at, who you’re expecting to exhibit problem behavior, whether shouting in the hallway is interpreted as a bullying event, or just kids roughhousing,” he said.

Kern High School District — based in Bakersfield with more than 42,000 students — had the highest rate of instructional time lost among African American students, totaling 80 days per 100 students.

EdSource reached out to the Kern High School District regarding the study’s findings, but district spokespeople did not respond by EdSource’s deadline.

Kern’s number is disappointing, said Ashley De La Rosa, the education policy director for the Central Valley-based Dolores Huerta Foundation, which previously sued the Kern High School District over its disciplinary methods. But she said she’s “not surprised either.”

“The current board of education seems more focused on monitoring and policing students than actually seeing what the teachers or the administrators are doing,” De La Rosa said. “… When students are not in class, they’re not learning, and our educational attainment in Kern County is one of the lowest.”

She noted that the Kern High School District made some progress after a 2014 lawsuit alleged its higher rates of suspension for students of color were discriminatory.

According to an announcement released by the Dolores Huerta Foundation, a 2017 settlement had required Kern High School district to “implement positive discipline practices to address disparate discipline outcomes and provide discipline-related training to all staff and personnel operating within the school environment.”

But after the terms of the settlement expired and the Covid-19 pandemic struck in 2020, the district took a major step back and out-of-school suspensions began to increase once again, De La Rosa said.

But following the 2017 settlement, the district said in that “certainly, KHSD has not engaged in intentional systemic racist student discipline practices against African-American and Latino students.”

“Rather (Kern High School District), like most public school districts nationwide, has been reviewing its student discipline data as it impacts minority students, and reframing its student discipline practices in order to address the statistically disproportionate suspension and expulsion of students of color,” the district’s statement noted.

By comparison, LAUSD’s rate of lost instructional days for African American students was 40 times lower than Kern’s, and no single demographic group lost more than three days per 100 students, according to the report.

A district spokesperson and community activists have attributed LAUSD’s reduction in out-of-school suspensions to the elimination of “willful defiance” suspensions 10 years ago, which was achieved through a School Climate Bill of Rights.

Willful defiance suspensions, advocates argued, were used as punitive disciplinary practices for small, subjective infractions such as talking back to a teacher or refusing to spit out gum.

Since the bill of rights passed, the district’s suspension rate has dropped from 2.3% in the 2011-12 academic year to 0.3% in 2021-2022, according to a district spokesperson. Meanwhile, LAUSD has worked to incorporate alternative disciplinary methods rooted in restorative justice.

“I’m proud of the progress LAUSD has made and the recognition in this report, and I also know that our progress resulted from years of community pressure and advocacy to treat students like the learners they are. As they learn literacy and mathematics, they also learn behavior expectations, conflict resolution skills and restorative practices,” LAUSD board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin said.

“If we can shift the hearts, minds and skills of nearly 70,000 employees in LAUSD, then surely other districts can too,” she said.

Still, LAUSD remains “far from perfect” and has reported students to the police at higher rates than average, according to the report.

“We’re often punishing those that need the most support. So this is a (really) important opportunity … to do more radical listening, making sure that we have the right wraparound support necessary for students to thrive, particularly those students who are often in the shadows, often neglected and nothing more,” said Ryan J. Smith, the chief strategy officer at Community Coalition.

He also stressed that the district should prioritize support services, including psychiatric social workers and counselors, to uplift more vulnerable students who often make transitions from one home and community to another.

Looking ahead

According to the California Compilation of School Discipline Laws And Regulations, suspensions, regardless of whether they are out-of-school suspensions, should only be used as a last resort — and can only be used if a student exhibits certain behaviors, including causing physical injury to others or possessing illegal drugs.

Earlier this month, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 27, which aims to halt all suspensions for one of those categories, willful defiance, for middle and high school students across the state.

Losen said that despite statewide attempts to end willful defiance suspensions, he is still concerned that “violence with no injury” suspensions could take its place as another subjective, umbrella category that could disproportionately harm marginalized students.

“California has made some progress, but there’s a great amount of work to be done, and much more that could be done. I don’t want to lose sight,” Losen said. “Modest progress shouldn’t kill the initiative to really make more lasting, substantial changes.”