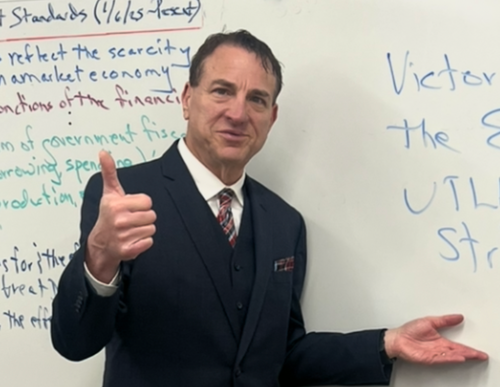

Glenn Sacks is a veteran social studies teacher in a Los Angeles public high school. Many of the students he teaches are immigrants. He describes here what he has learned about them.

Teacher Glenn Sacks

“If they spit, we will hit, and I promise you, they will be hit harder than they ever have been hit before. Such disrespect will not be tolerated!” — Donald Trump

President Trump says he is defending Los Angeles from a “foreign invasion,” but the only invasion we see is the one being led by Trump.

Roughly a quarter of all students in the Los Angeles Unified School District are undocumented. The student body at the high school where I teach consists almost entirely of immigrants, many of them undocumented, and the children of immigrants, many of whose parents and family members are undocumented. This week we held our graduation ceremony under the specter of Trump’s campaign against our city.

Outside, school police patrolled to guard against potential Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids. Amidst rumors of various actions, LAUSD decided that some schools’ graduations would be broadcast on Zoom.

For many immigrant parents, graduation day is the culmination of decades of hard work and sacrifice, and many braved the threat of an ICE raid and came to our campus anyway. Others, perhaps wisely, decided to watch from home.

They deserve better.

Trump’s Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem calls us a “city of criminals,” and many Americans are cheering on the Trump administration and vilifying immigrants. What we see in LAUSD is an often heroic generation of immigrant parents working hard to provide for their children here while also sending remittance money to their families in their native countries. We see students who (usually) are a pleasure to teach, and parents who are grateful for teachers’ efforts.

Watching the students at the graduation ceremony, I saw so many who have had to overcome so much. Like the student in my AP U.S. government class who from age 12 worked weekends for his family’s business but made it into UCLA and earned a scholarship. There’s the girl who had faced homelessness this year. The boy with learning issues who powered through my AP class via an obsessive effort that his friends would kid him about, but which he committed to anyway. He got an “A,” which some of the students ribbing him did not.

Many students have harrowing, horrific stories of how they got to the U.S. — stories you can usually learn only by coaxing it out of them.

There’s the student who grew up in an apartment complex in San Salvador, where once girls reached a certain age they were obligated to become the “girlfriend” of a member of whatever gang controlled that area. When she was 14 they came for her, but she was ready, and shot a gang member before slipping out of the country, going all the way up through Guatemala and Mexico, desperate to find her father in Los Angeles.

As she told me this story at parent conference night, tears welled up in her father’s eyes. It’s also touching to watch their loving, long-running argument — he wants her to manage and eventually take over the small business he built, and she wants to become an artist instead. To this day she does not know whether the gang member she shot lived or died.

At the graduation ceremony, our principal asks all those who will be joining the armed forces to stand up to be recognized. These students are a windfall for the U.S. military. I teach seniors, and in an average class, three or four of my students join the military, most often the Marines, either right out of high school or within a couple years.

Were these bright, hard-working young people born into different circumstances, they would have gone to college. Instead, they often feel compelled to join the military for the economic opportunity — the so-called “economic draft.”

Some also enlist because it helps them gain citizenship and/or helps family members adjust their immigration status. A couple years ago, an accomplished student told me he was joining the Marines instead of going to college. I was a little surprised and asked him why, and he replied, “Because it’s the best way to fix my parents’ papers.”

Immigrants are the backbone of many of our industries, including construction and homebuilding, restaurants, hospitality and agriculture. They are an indispensable part of the senior care industry, particularly in assisted living and in-home care. Of the couple dozen people who cared for my ailing parents during a decade of navigating them through various facilities, I can’t remember one who was not an immigrant. There is something especially disturbing about disparaging the people who care for us when we’re old, sick, and at our most vulnerable.

Immigrants are woven into the fabric of our economy and our society. They are our neighbors, our co-workers, our friends, and an integral part of our community. The average person in Los Angeles interacts with them continually in myriad ways — and without a thought to their immigration status.

Immigrants are also maligned for allegedly leeching off public benefits without paying taxes to finance them. This week conservative commentator Matt Walsh called to ”ban all third world immigration″ whether it’s “legal or illegal,” explaining, “We cannot be the world’s soup kitchen anymore.”

One can’t teach a U.S. government and politics class in Los Angeles without detailing the phenomenon of taxpayers blaming immigrants for the cost of Medicaid, food stamps and other social programs. My students are hurt when they come to understand that many Americans look at their parents, who they’ve watched sacrifice so much for them, as “takers.”

Nor is it true.

Californians pay America’s highest state sales tax. It is particularly egregious in Los Angeles, where between this and the local surcharge, we pay 9.75%. As I teach my economics students, this is a regressive tax where LAUSD students and their parents must pay the same tax rate on everything they buy as billionaires do.

Moreover, most immigrants are renters, and they informally pay property taxes through their rent. California ranks 7th highest in the nation in average property taxes paid.

Our state government estimates that immigrants pay over $50 billion in state and local taxes and over $80 billion more in federal taxes. Add this to the enormous value of their labor, and America is getting a bargain.

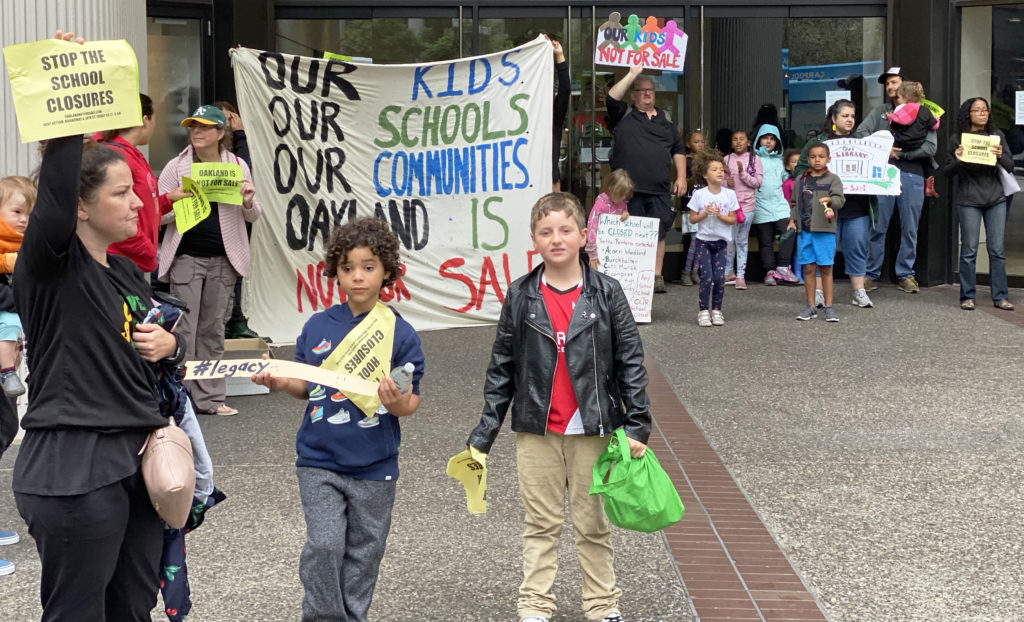

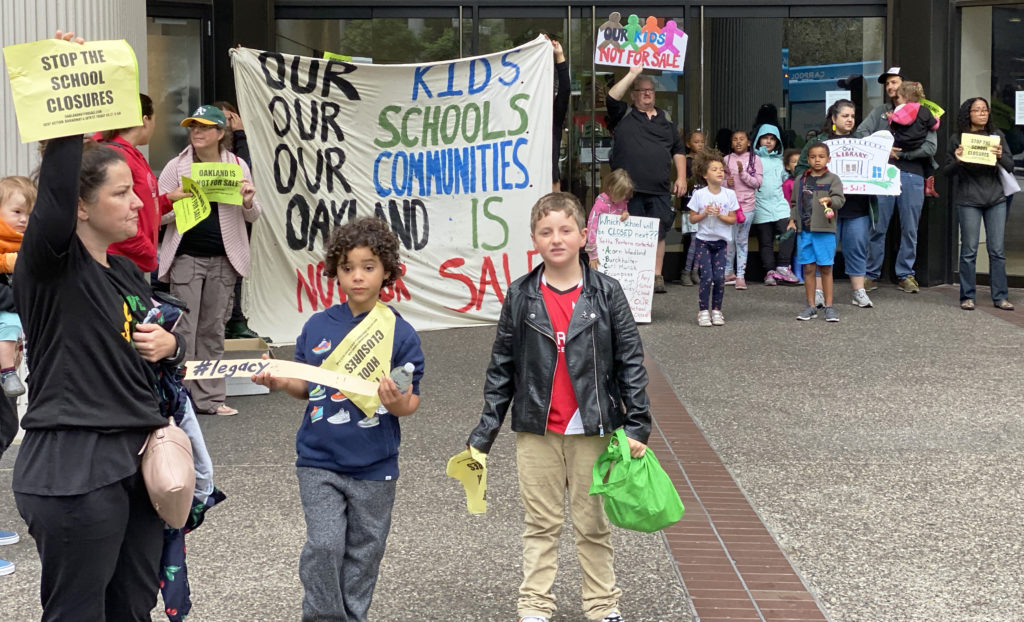

Part of what is driving the current protests is the sense that once somebody is taken by ICE, their families won’t know their fate. Where will they be sent? Will they get due process? Will they end up in a Salvadoran megaprisonwhere, even if it’s ordered that they be returned home, the president may pretend he can’t get them back? It is fitting that the flashpoint for much of the protests has been the federal Metropolitan Detention Center downtown.

We also question the point of all this, particularly since the Trump administration can’t seem to get its story straight as to why ICE is even here.

Trump’s border czar Tom Homan says the raids are about enforcing the laws against hiring undocumented workers and threatens “more worksite enforcement than you’ve ever seen in the history of this nation.” By contrast, Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin, citing “murderers, pedophiles, and drug traffickers,” says the purpose of the raids is to “arrest criminal illegal aliens.”

And now, having provoked protests, the Trump administration uses them as a justification for escalating his measures against Los Angeles.

Amid this, our graduating students struggle to focus on their goals. One Salvadoran student who came to this country less than four years ago knowing little English managed the impressive feat of getting an “A” in my AP class. He’d sometimes come before school to ask questions or seek help parsing through the latest immigration document he’d received. Usually, whatever document I read over did not provide him much encouragement.

He earned admission to a University of California school, where he’ll be studying biomedical engineering. Perhaps one day he’ll help develop a medicine that will benefit some of the people who don’t want him here.

When we said goodbye after the graduation ceremony, I didn’t know what to say beyond what I’ve often told him in the past — “Just keep your head down and keep marching forward.”

“I will,” he replied.

Glenn Sacks teaches government, economics, and history in the Los Angeles Unified School District. His columns on education, history, and politics have been published in dozens of America’s largest publications.