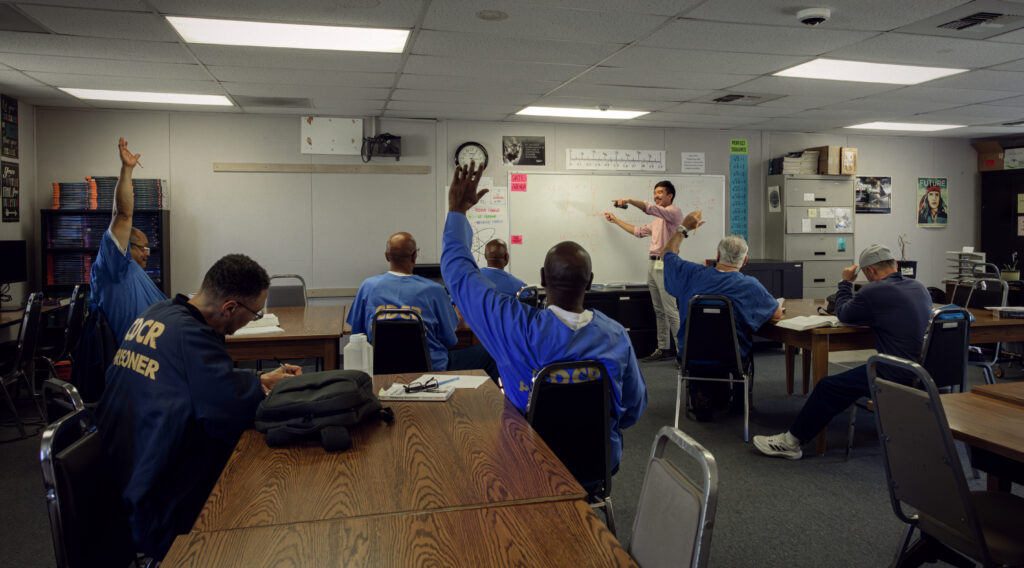

Oakland International High math teacher David Hansen teaches newcomer immigrant students fractions using the game of checkers.

Theresa Harrington/EdSource

As soon as Jenna Hewitt King asked students in her senior English class for newcomers to introduce themselves, she knew she was in over her head.

“I saw this look of fear in their faces, like, ‘What? I have to talk out loud?’ There was a lot of whispering in their home language,” said King, who also wrote a commentary about the experience for EdSource. “We were both looking at each other like deer in headlights and you could sense this was not something that any of us were prepared for.”

A bill signed over the weekend by Gov. Gavin Newsom, Assembly Bill 714, will begin to provide much-needed guidance and data for teachers like King, who often don’t have training or experience in how to teach newcomer students — defined as students between 3 and 21 years old who were born in other countries and have attended school in the U.S. for fewer than three years.

King had expected to be able to teach the class in a way similar to how she teaches other senior English classes at San Leandro High School in Alameda County. Those students read three novels over the course of the year and write multiple essays.

But the students in her newcomer class had recently arrived from other countries and did not know much English. Most of them spoke Spanish, and a few spoke Mandarin or Cantonese.

King speaks only English and had no experience or training in teaching English language development to students learning English as a second language, let alone students new to the country.

“I was just ridiculously ill-prepared. Teaching English in high school, we don’t teach phonics, we don’t teach language in the immense detail that elementary or English learner teachers do,” King said. “Most of last school year was me running around like a crazy person asking ELD teachers on campus, ‘What am I doing? What can you share with me?’”

King’s experience is not an isolated one. Researchers and educators who work with teachers throughout California say it is common for teachers of newcomer students to feel unprepared.

“What happens is that they’re basically thrown into the classroom and it’s either sink or swim,” said Efraín Tovar, who teaches seventh and eighth grade newcomer students at Abraham Lincoln Middle School in Selma Unified School District in the Central Valley and is also founder and director of the California Newcomer Network.

Tovar said most school districts, charter schools and county offices of education do not have experts in teaching newcomers.

Assembly Bill 714 will require the California Department of Education to put together a list of resources on best practices and requirements for teaching newcomer students. In addition, the law requires the state to consider including content on newcomers in the next revision of the English Language Arts and English Language Development curriculum framework and to include resources on newcomer students in any new instructional materials for grades one to eight.

“As a teacher, I’m excited. It’s historic. It’s a light. It’s hope,” Tovar said. “Finally, newcomers are being brought to the forefront.”

The bill also requires the state’s Department of Education to report the number of newcomer students enrolled and their countries of origin. There were about 152,000 newcomer students enrolled in California schools in 2020-21, according to data obtained from the state by Californians Together, but this data is not readily available to the public.

Separating data on newcomers from other English learners is important, said Jeannie Myung, director of policy research at Policy Analysis for California Education, or PACE, an independent research center at Stanford University that focuses on education.

“We know that what we don’t measure, we don’t really understand, and what we don’t understand, we can’t really improve,” Myung said.

The bill originally would have also required the department to report newcomers’ scores on standardized tests, to be able to compare them to other groups of English learners. But that requirement was removed from the final version of the legislation.

In 2021 and 2022, PACE brought together leaders from California’s departments of Education and Social Services, the Legislature, school districts and universities to discuss how to improve newcomer education, resulting in six reports on newcomers in the state.

Myung said there is expertise and knowledge about how to best teach newcomers, and how it is different from teaching other English learners, but that information is not reaching most teachers.

“California’s a local control state, and local control is often good in decision-making. But local control shouldn’t mean that every teacher in every classroom is repeating the wheel when it comes to how to educate newcomer students,” Myung said.

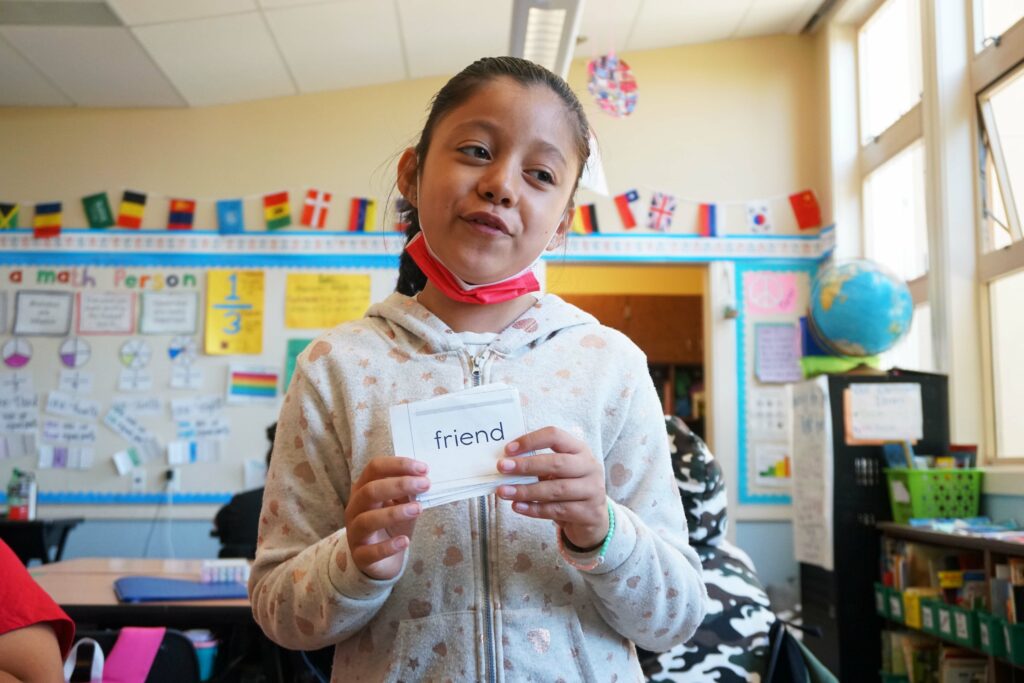

Myung said an example of best practices is materials created for older newcomer students. Most texts available for English learners are created for younger students, but many newcomers are often teenagers, who would find a picture book about playing with a toy too juvenile. They need access to materials that are at their level of English but also deal with content at their age level, she said.

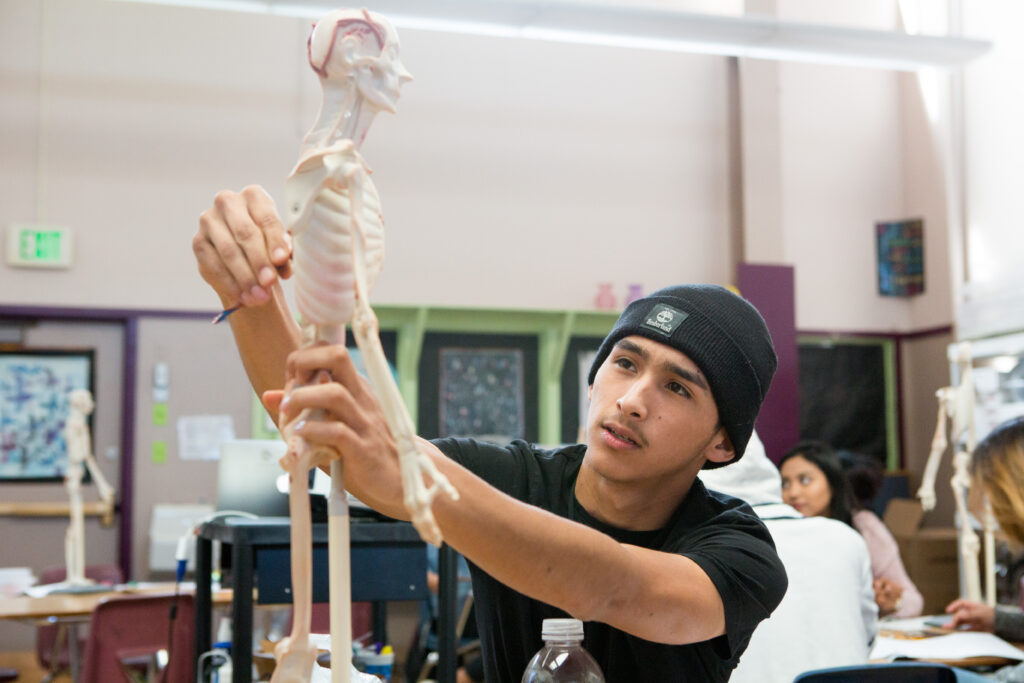

In addition, teachers need to know how to help students who speak different home languages talk to each other in English.

In King’s class at San Leandro High, she relied on Google Translate to communicate with her students. After realizing her students would not be able to read the novels she had planned for other seniors, she scrambled to find other materials. She found one novel written in short poetry with pictures, and she had her students watch a movie version of another novel and then read short excerpts of it rather than the whole text. This year, she is using some books in students’ home languages, but she is still struggling to figure out how to facilitate discussion between them.

“If you can imagine having a group of newcomers where you have three, four, five, maybe up to eight languages represented in your classroom, that requires a special skill set,” Tovar said.

Newcomer students also need support understanding their new communities in the U.S. and how they fit into them, said Magaly Lavadenz, executive director of the Center for Equity for English Learners at Loyola Marymount University.

“It’s not just about teaching them to learn English better, but how to better integrate into society and be a fully participatory citizen,” Lavadenz said.

Lavadenz said it is crucial for schools to help newcomer students and families access social services they may need, like food, housing and mental health therapy.

As a teacher in Glendale Unified in the early 1990s, Lavadenz said she saw many students who had fled war in Central America draw pictures of the violence they had witnessed. She saw that again while conducting a case study of San Juan Unified’s newcomer program, published by PACE. She said children were asked to draw the flags of their countries and one boy from Afghanistan described his drawing by saying, “Red is the color of blood spilling on the streets.”

“These are things that children should not see, that we should not see as adults. They’re seeing this and they’re experiencing this, and those images stay with them,” Lavadenz said. “That experience opened my eyes about what the effects of trauma are on young children and how schools could be more ready.”

King said AB 714 is a small but good step forward.

“I still haven’t received any additional training,” she said. “Each time I ask, I’m told, ‘Yeah, find a training.’ I don’t know where to go or what to do.”