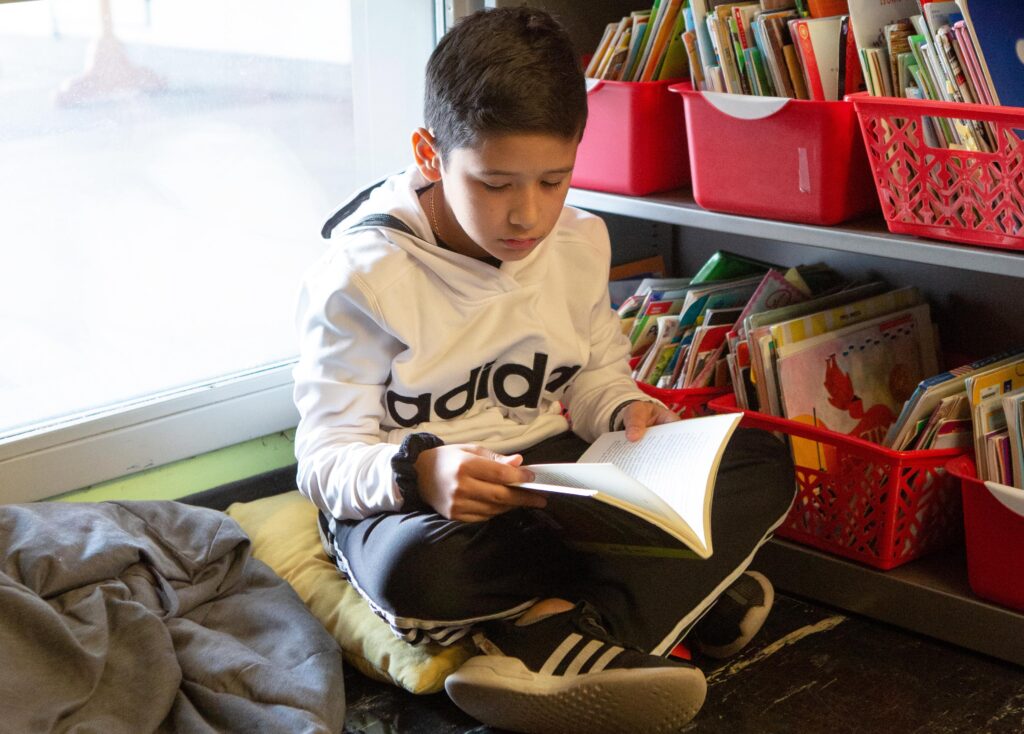

Is this a picture of something bad, or something good?

Cognitive scientists call this the global-local processing dilemma: Do we perceive the overall image, or focus on the details? Education policy often faces the same question: Can a policy be considered “good” if the overall data look promising, but the day-to-day experiences feel “bad?”

This tension is at the heart of California’s college math reforms.

Like the image, the story of these policies may look “good” from a distance, but “bad” up close.

Before recent reforms, community college students who needed extra math support were typically placed in remedial courses like elementary algebra. These classes didn’t count toward transfer requirements, and most students stuck in them never made it to a math course needed to transfer to a four-year university, such as college algebra or introductory statistics. This created an academic dead end for many.

A 2017 law, Assembly Bill 705, changed that. It used high school grades for placement and gave more students direct access to transfer-level courses, with corequisite support (a support course taken concurrently with a transfer-level course) when needed. Instead of multi-semester remediation, students could move into transfer-level math courses faster.

While challenges remain, the approach led to significant improvements. In 2016-17, before AB 705 was announced, only 27% of students passed a transfer-level math course within one year. But in 2019-20, the first full year of AB 705’s implementation, that number had nearly doubled to 51%. And by 2023-24, it reached 62%. About 30,000 more students were fulfilling their math requirements each year. The story is similar in English courses, and so it’s undeniable that AB 705 has helped California’s community college students get one step closer to transfer.

Despite these gains, many faculty don’t see AB 705 as a success. As one instructor put it, “There are a lot more people failing than before … largely students of color. … By making this change (i.e., AB 705) around equity, we’ve created an inequitable system.” And the data do show that pass rates have declined.

But here’s the catch: Far more students are now taking those courses. The graph below helps illustrate this shift using data from one community college district. Before AB 705, only a small fraction of students reached transfer-level math, but with high pass rates, as shown by the darker blue shading within the dashed box. After AB 705, access expanded, but pass rates declined from 80% to 70%. Critically, that’s 70% of a much larger group.

With such an improvement, why do some faculty feel like the policy is a failure?

Because of this paradox: AB 705 absolutely led to more students passing. But it also led to more students failing.

People respond more strongly to stories than to statistics, and losses loom larger than gains. The students we see struggling — their faces, their frustration, their stories — linger longer than a bar graph showing statewide gains. As faculty members, we know this all too well. We remember the students who didn’t make it. We think about what we could’ve done differently. We agonize over them.

And often, faculty haven’t been given the full picture. Our research has found that many instructors hadn’t even seen outcome data on AB 705’s impact. So, without that context, and given the classroom experience, it’s reasonable to assume the policy failed.

This disconnect is a classic challenge in public policy: a policy can be effective overall but still feel painful on the ground. And this tension is always a part of the hard work of building systemic justice. AB 705 succeeded in dismantling long-standing barriers and expanding access to transfer-level math. But that progress has introduced new classroom dynamics that feel personal, urgent and overwhelming to faculty. Good policy must account for both the big-picture gains and the human cost of change. Reforms don’t succeed on data alone. They require understanding, empathy and support for those doing the work.

And just as faculty were beginning to adjust to AB 705, we face Assembly Bill 1705, a sharper and even more controversial new policy. It asks colleges to stretch even more, limiting their ability to offer even prerequisite math courses. Understandably, many educators are still reeling. They’re trying to adapt to new expectations while managing unintended consequences in their classrooms. Recent guidance has softened the rollout, but confusion remains. The stakes are high, and many faculty feel mistrustful and angry.

If AB 705 taught us anything, it’s that mistrust grows when there’s a gap between what the data show and what people experience. This is why the next phase of work cannot be just about compliance or policy enforcement. It must be about storytelling, listening and solutions. Faculty need to see the big picture. Policymakers need to understand life on the ground. The policy “worked” in aggregate, but not without professional and emotional cost. If we ignore that, we risk undermining the very equity goals these reforms were meant to achieve.

Like the image above, the truth lies in seeing both levels clearly. We must acknowledge the trade-offs, the tension, and the very real pain of transition. Let’s take concerns seriously without retreating from hard-won progress. Let’s keep asking the harder, more honest questions: How do we support both students and faculty through ambitious change? How do we ensure that every student, not just the most prepared, has a real shot at success?

If we can do that, maybe we’ll find a way forward that is both honest and hopeful, one that sees the whole picture.

•••

Ji Y. Son, Ph.D., is a cognitive scientist and professor at California State University, Los Angeles and co-founder of CourseKata.org, a statistics and data science curriculum used by colleges and high schools.

Federick Ngo, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His research examines higher education policy, with a focus on college access and community college students.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the authors. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.