Credit: Thomas Galvez/Flickr

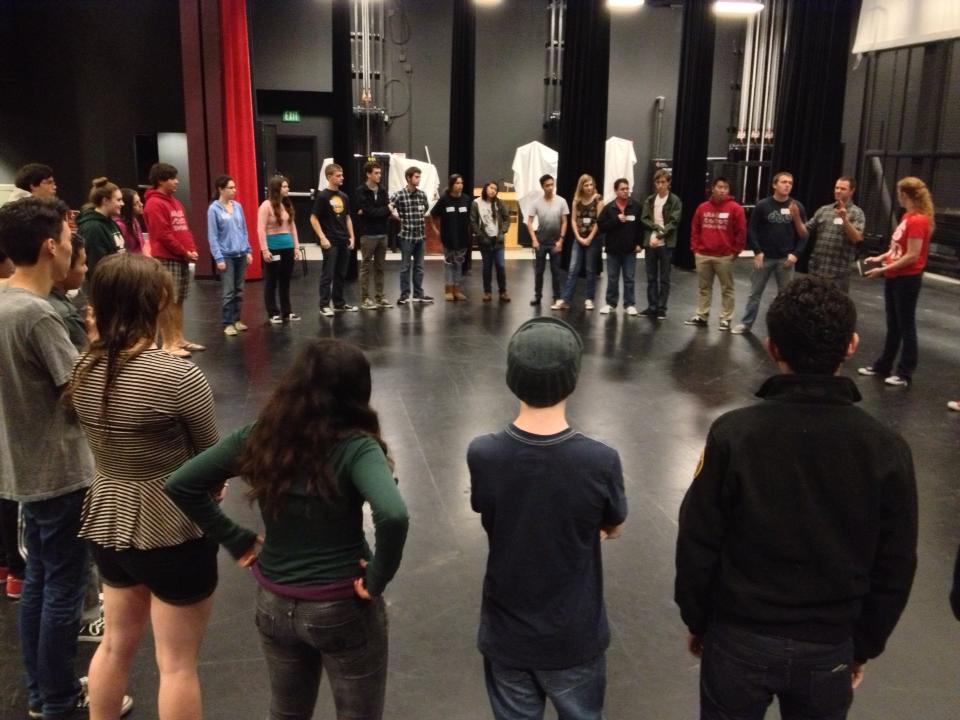

Nearly 45 years ago, in the fall of 1978, teachers across Fresno Unified stood at the gates of their schools, rather than in front of dozens of students in the classroom. They’d made a decision to participate in what is still the district’s only strike in history.

Students were no longer with the teachers they’d grown to know. They had to contend with substitute teachers or administrators who gave them packets of work in combined classrooms or in the cafeteria.

As the two-week-long strike continued, some teachers returned to their classrooms, while others, with signs in hand, remained on strike to demand better working conditions.

“At many schools, it was very traumatic, especially for the younger ones,” retired teacher Barbara Mendes said. Mendes, 84, was the teachers union representative at Lane Elementary and had been teaching for about three years when she and others went on strike in 1978.

Each day, Mendes and other Lane Elementary teachers, standing at the school’s perimeter, greeted students in the mornings as they entered school and again in the afternoon as they left.

“Just to smile,” Mendes said. “Just a smile at the students, so they’d know we were OK and that they’d be OK.”

That smile, a “hey” or a handshake were subtle ways to mitigate the effects of the strike, which was meant to put pressure on the district but affected students as well.

Fast forward 40 plus years: Thousands of teachers in the over 70,000-student school district must, once again, choose whether to walk away from their students in a standoff with the district, which must decide if not compromising with teachers on contested issues is what is best for Fresno Unified students.

Both sides must take steps to bridge a widening communication gap before a heated strike makes matters worse, as it did in 1978.

While the 1978 strike eventually led to better communication between the district and union — a victory, it also damaged relationships among teachers and shattered whatever trust existed between teachers and administrators.

40 years later, teachers are fighting for the same issue

Collective bargaining for teachers in California started in the mid-to-late 1970s, and the 1978 contract that resulted from the strike was the first-ever negotiated agreement between Fresno Unified and its teachers union, according to Nancy Richardson, 78, who was first elected to the school board in 1975. Other employee unions, Richardson said, closely monitored contract negotiations and strike actions with plans to come to the district for “me too” clauses on pay and benefits.

Back then, the school district had also just desegregated staff and schools, Richardson said, so tensions were already high.

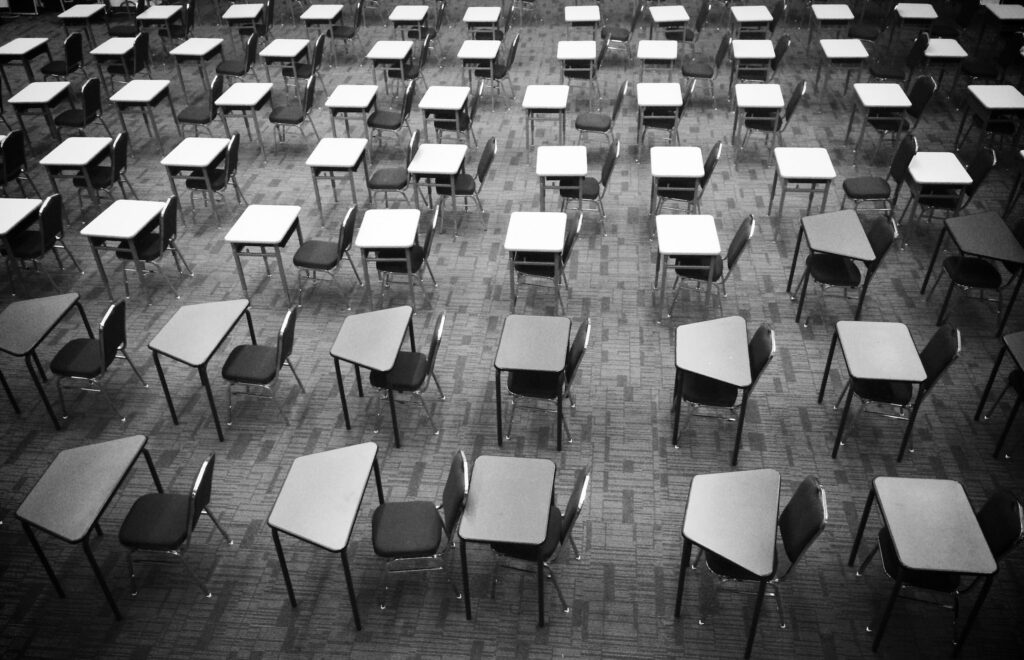

However, class size was the driving force for the 1978 strike, something current teachers know too well.

“We just wanted our class size lowered,” Mendes said, whose husband was also a teacher. She can’t recall the exact language of the union’s proposal for reducing class size but said that “anything would’ve been better” than what many teachers had to endure each day.

“My husband had so many children in his high school classroom, he had some of them sitting on the vents that ran along the window,” she said. “He didn’t have enough desks.”

Now, in 2023, the teachers union wants class sizes capped, in addition to a change in contract language offering parents the choice of moving their children to smaller classes before the cap is exceeded or giving teachers an increased stipend.

Strike was ‘devastating’ for staff

The 1978 strike lasted between eight and 10 days. To this day, people’s recollection of the strike differs because some educators crossed the picket line.

Some teachers can’t afford to go without the pay, Superintendent Bob Nelson said.

“They have to make very hard decisions about what they intend to do,” he said. “That puts teachers at odds with one another.”

It was difficult for Mendes and her husband, who started working in the district office later in his career and who joined the strike, to go 10 days without a salary, and just as hard to watch their colleagues return to work because they had no choice.

“It was hard on them,” Mendes said. “They had bills to pay. They went back for monetary reasons, not because they changed their minds about the reasons for the strike.”

Those who returned to their class before the strike ended were often chastised by others for that decision, Mendes and Richardson recall. So during and after the 1978 strike, Mendes worked to mend relationships. While she views her reconciliation efforts at her elementary school as somewhat successful, she admitted that many relationships elsewhere never recovered.

“There are teachers, to this day, who won’t speak to each other because one struck and the other one didn’t,” Mendes said.

Richardson summed up the lifelong impact of the strike experience in one word: devastating.

“Nobody gets out without damage,” she said. “There wasn’t anybody who wasn’t scarred.”

And that went for administrators too.

Principals, responsible for keeping schools running, were left with angry teachers divided by the strike, she said.

As school board president, Richardson was the face of the board, and she was bombarded with angry calls about class size, pay and benefits, and even threatening messages.

The teachers union at the time posted the school board members’ phone numbers. Messages, such as, “You’re going to pay for this,” made Richardson fear for her children’s safety.

She graphically detailed how members of the union held a candlelight vigil outside her home and walked up and down her street, frightening her fifth-grade daughter. Richardson’s daughter has distinct memories of that moment, but not any of the reasons behind the strike.

“Things happened that people never forget,” she said.

This year’s collapsed negotiations may lead to district’s second strike

Even though the last teachers strike was 45 years ago, the school district and teachers union have been on the brink a few times. In 2017, teachers voted to strike, but a third party stepped in and negotiated a compromise.

This time is very different from 2017, both Fresno Unified and the Fresno Teachers Association say.

Manuel Bonilla, union president since July 2018 and a member of its bargaining team before that, said a strike seems more “urgent and real” to address what has become teachers’ daily work: meeting students’ social-emotional needs.

“I think people are more upset now by the ignoring of the issues — of the disconnect of the reality of what people are going through,” Bonilla said.

In a way, teachers shouldered the school system’s burden by going above and beyond their duties during and following the pandemic, he said, but now, teachers feel “undervalued.”

Superintendent Nelson attributes the differences between now and 2017 to Sacramento City, Los Angeles and Oakland school districts pursuing strikes in line with what he considers a California Teachers Association playbook that unions are following.

“It feels like what has happened in other school districts up and down the state,” he said.

In 2017, when teachers voted to strike, teachers hadn’t worked under a contract in 18 months, according to Nelson, who’s been superintendent since 2017. This year, teachers are just over three months out of the previous contract, and teachers are even closer to a strike, he said.

“We’re just in a different place now (from 2017),” Nelson said.

The school district and teachers union have declared an impasse in negotiations and failed to reach an agreement despite multiple mediation attempts. In late May, upon giving its last offer, the Fresno Teachers Association imposed a Sept. 29 deadline for the school district to agree on a contract or face an Oct. 18 strike vote.

The district and union did not meet that deadline.

Mending relationships, rebuilding trust becomes more challenging if strike happens

At this point, weeks ahead of a possible strike, scant trust exists between FUSD administration and teachers. This has likely worsened over time, Richardson said.

“I’m sure they (board members and district leaders) know how extremely problematic it is to get to this point — or go further — because of the erosion of trust,” she said. “And I’m sure they know that whenever there is a strike, anywhere, building back trust takes so long and is so difficult.”

Mendes, the retired teacher, believes the only way for the district and union to avoid a strike is for the district to “really listen” to teachers and for there to be better communication between them.

“Listen to what their problems are,” she said over and over. “Don’t tell them what they should be thinking. Just listen to what the teachers are complaining about and promise to do something about it.”

If it takes a strike for that communication to happen, rebuilding trust becomes an even greater challenge.

The 1978 strike might’ve lasted longer than it had, if not for communication.

Richardson, according to Mendes, visited various schools to talk to striking educators.

“Seeing us on the picket line broke her (Richardson’s) heart,” Mendes said.

Eventually, Richardson, union leaders and the superintendent met to discuss ways to end the strike.

“We did that sitting down together,” Richardson said.

She urges teachers and administrators to consider what could be lost if teachers strike.

“Think about how it’s going to go afterwards,” she said, “and focus on the kindness and respect it will take for people to work together successfully afterwards.”

But is a strike worth it?

The teachers’ strike in 1978 didn’t quite lead to lower class size, Mendes said, but teachers had an impact.

“I think that it was important to let the teachers know that they could do something that would make an impact, as hard as it was on everybody,” she said.

Still, four decades later, Mendes isn’t sure if that impact outweighed the trauma and broken relationships.

“Every strike is questionable,” she said. It was rewarding for those who took part, she said, and it opened lines of communication.

Even so, was the strike worth it?

“I don’t know; I really am not sure,” Mendes said. “But it does get the attention (of the school district).”