“Decentering the book.” Thanks but no thanks.

This week I’ve been posting excerpts from the forthcoming book on reading I’ve been writing with Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway–it’s tentatively going to be called The Teach Like a Champion Guide to the Science of Reading. Today I’m sharing the first few pages of our chapter on Attention, which is of the most important factors teachers of reading and English have to consider, especially now...

If you want to find out more, sooner, please join us for our Nashville workshop Dec 5 and 6.

Chapter 2: Attending to Attention

The universal adoption of smartphones and other digital devices has changed the life of every young person we teach.

The changes wrought have been at times promising and at times foreboding; sometimes both things at once. Sometimes, given the pace and complexity of the changes, it’s hard to even say what they mean and what their consequences will be.

And, of course, we experience a version of those changes alongside our students. As we write this, for example, we note that we are shortening our sentences. We are told that readers will be far less likely to persist in reading this if the sentences are too long and complex.

The decline of attentional skills associated with time spent in a digital world of constant distraction means that both we and our students find tasks that require sustained concentration—like making sense of a long-ish sentence—a little harder. And when it comes to harder things, we are a little less likely to persist than we once were.

Spare a thought for poor Charles Dickens. The mark of his craft was the intertwining of multiple ideas and perspectives within a single, complex sentence. The resulting sentences could be 30 or 40 words in length. With writing like that, he’d struggle to find readers in the 21st century. In fact, in most classrooms he does struggle—and for exactly that reason.

The fact that his books are long used to be a positive attribute. He was the 19th century’s most popular English-language writer, not so much despite his lengthy writing but because of it. Picking up David Copperfield (1024 pages) was, to a 19th century audience armed with the stamina to read without interruption for hours at a time, more or less like binge-watching a Netflix series today[1]. You built your evenings around it.

Today long, like complex, is not a virtue. There is internet slang for this: tl;dr (too long; didn’t read), which the Cambridge dictionary glosses as: “used to comment on something that someone has written…: If a commenter responds to a post with ‘tl;dr,’ it expresses an expectation to be entertained without needing to pay attention or to think.”

Even in university settings, tl;dr is in the zeitgeist. “Students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages and seem to walk away from reading of as little as 20 pages with no real understanding,” one professorrecently wrote[2].

“Fewer and fewer are reading the materials I assign. On a good day, maybe 30 percent of any given class has done the reading,” wrote another.[3]

Yet another professor notes “I’ve come to the conclusion that assigning students to read more than one five-page academic-journal article for a particular class session is, in sum, too much.”[4]

In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari chats with a Harvard professor who struggles to get students “to read even quite short books” and so now offers them “podcasts and YouTube clips … instead.”

And in an Atlantic piece on “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” a first-year student at Columbia University told her required great-books course professor that his assignments of novels to be read over the course of a week or two were challenging because “at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.”[5]

Reading, increasingly, is too hard, too long, too tedious to minds attuned to the arrival of novel stimulus every few seconds—or at least it is if we make no effort to rebuild attention[6]. We’ll talk about some ways to do that in the classroom in this chapter, but consider for now one of the simplest ways to do this:,to give reading checks or quizzes at the start of each lesson: five to seven questions that are easy to answer if you’ve read carefully and hard to answer if you’ve read a summary or skimmed a bit here and there, and that will help train your students in what to pay attention to in a text[7].

Then again, we could ask: is this just moral panic? The judgment of every generation that the subsequent one is lacking? It’s an important question to ask, but the answer is: Probably not. There’s a lot of science to suggest measurable changes to attention.

Research tells us that your nearby cellphone, even turned off and face down on a table, distracts you. A 2023 study by Jeanette Skowronek and colleagues assessed how students performed on a test of “concentration and attention” under two conditions: when a phone was visible nearby but turned off, or when it had been left in another room. They found that “participants under the smartphone presence condition show significantly lower performance … compared to participants who complete the attention test in the absence of the smartphone.” In other words, “the mere presence of a smartphone results in lower cognitive performance.”[8]

Similarly, University of Texas professor Adrian Ward and colleagues found that even unused, “smartphones can adversely affect… available working memory capacity and functional fluid intelligence[9].” Part of the reason for this is that it takes cognitive resources to inhibit the impulse to look at it as soon as you are aware of its presence.

You see a device and it triggers a desire to find out what’s become new in the past fraction of a minute. While it doesn’t even need to be turned on to have this effect, it usually is, of course. And turned on—almost always on and constantly attended to—means an attractive distraction from a difficult task pushed into your consciousness every few seconds. For those of us exposed to screens—including many of the teens we see in our classrooms—this has rewired not only the ways they think when their phones are in-hand but the ways they think, period.

While this surely demands greater reflection among schools, most relevant to this book are the particular implications those changes have for reading and reading teachers.

The Book is Dying

Consider the fact that far fewer students read for pleasure compared with just a few years ago. For time immemorial, we teachers have cajoled, encouraged and prodded students to read on their own. But even multiplying our efforts tenfold now won’t get us back to baseline reading rates of, say, 2005. The numbers of students who read outside of school and the amount of reading they do have fallen through the floor.

Take data gathered by San Diego State professor Jean Twenge. She has studied responses by about 50,000 nationally representative teens to a survey that has been administered since 1975, enabling broadscale changes over time to be easily observed and tracked[10].

In 2016, Twenge found that 16 percent of 12th grade students read a book, magazine or newspaper on their own regularly[11].

That’s about only half of the 35% of students who reported doing so as recently as 2005.

The survey also found that the percentage of 12th graders who reported reading no books on their own at all in the last year nearly tripled since 1976, reaching one out of three by 2016.

This is dispiriting in its own right, but doubly so because 2016 was a long time ago, technology-wise—the salad days practically, before the precipitous rise in social media use post-2020[12] and the advent of the most recent wave of especially addictive social media platforms like TikTok.

And, of course, any type or amount of reading shows up just the same in the survey, whether it’s 100 pages of Dickens or a short article on Taylor Swift’s latest outfit. In other words, even a “yes” on the survey still belies changes.

“This is not just a decline in reading on paper—it’s a decline in reading long-form text,” Twenge noted.

Other studies of young people’s reading behavior are consistent with Twenge’s findings.

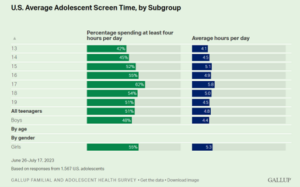

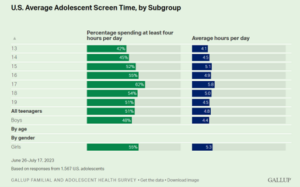

The 2023 American Time Use Survey found that teens aged 15 to 19 spent 8 minutes a day reading for personal interest. Compare that to the “up to 9 hours per day” the American teenager spends on screen time[13]. Teens in that age group reported spending, on average, roughly 5 hours per day on screens in the 2023 Gallup Familial and Adolescent Health Survey.

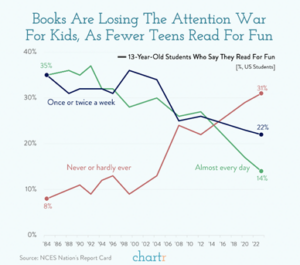

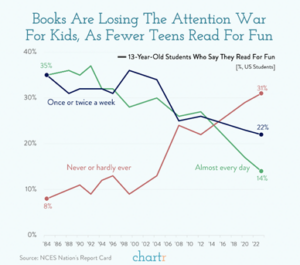

Data from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress show that the percentage of 13-year-old students who “never or hardly ever” read has increased four-fold since 1984, to 31 percent, while the percentage of students who read “almost every day” has dropped by 21 percent from that time, to 14 percent.[14]

As recently as 2000, classrooms were comprised of three to four times as many daily readers as non-readers. Now these numbers are reversed. There are now typically less than half as many students who read regularly outside of class as there are students who never do so.

Let’s hope, then, that they are reading books cover to cover inside our classrooms, because they almost certainly are not outside it.

What does it mean for our actions in the classroom if students are increasingly likely to be attentionally challenged, yet sustained reading is among the most attentionally demanding activities in which we can engage?

What are the implications for text selection in a world where the only books many students read will be the ones we assign?

What are the implications for fluency and vocabulary that they are less and less likely to read beyond the classroom walls?

What does it mean to assign nightly reading when we cannot assume that students will go home and read, when doing so requires them to resist the pull of a bright and shiny device far more compelling in the short run and always within reach?

What does it mean that even those students who go home and pull out the book as assigned read in a different cognitive state than we might hope or imagine, again with a phone likely competing for their attention?

Consider: One of us—we won’t say which—has a teenager whom we require to read regularly. We wish this teenager chose to read every day, but he doesn’t, and we love him and know that whether he reads is too important to leave to chance—or the version of “chance” in which the cards are stacked against him actually reading by behemoths of technology spending billions of dollars to fragment and commercialize attention. So, we’ve mandated he read three hours a week.

He read when he was 12, by the way—voraciously. Sometimes now he remembers the feeling it gave him and he sets out with the intention of reading again. He knows it’s good for him. He knows he loved it then and might love it again. But then, on the way to his room or the couch or the patio with a book in one hand, he glances at the phone in his other. The snapchats are rolling in. The Instagram notifications. There’s a feed of tailored videos—his favorite comedian; his favorite point guard.

Suddenly 20 minutes have passed. Then 40. The book has lost again.

But let us share this picture of him on one of his reading days: reclined on the couch with a copy of The Boys in the Boat held aloft—briefly!—but also with his cellphone resting on his chest.

Every few seconds the reverie he might have experienced, the cognitive state he might have been immersed in where the book transported him to the world of Olympic athletes, is interrupted.

Perhaps for a moment he imagines himself in a scull on a lake at dawn as he…

Bzzzz. Dude! Sup?

Is interrupted by every manner of trivial and alluring distraction…

Bzzzzz. U coming over? We at B’s.

… which results on net in a different type of engagement with the book. There is no getting lost in…

Bzzzz. That new point guard. Peep this vid. Filth, bro!

…a different world or context. The level of empathetic connection to the protagonist…

Bzzzz. When U gonna text Kiley from math class. Think she digs you!

…is just not the same.

The experience of reading a book with fractured concentration is qualitatively different.

Bzzzz.

So there is both a “less reading” problem and a “shallow reading” problem. And, as we will see, reduced application of focused attention over time can become reduced ability to pay attention.[15]

We have written about the broader effects of smartphones and the ubiquitous digital world elsewhere. So have others—often far more insightfully.[16] Here, we will skip over here profoundly important issues of welfare and mental health: anxiety, depression and the inexorable dismantling of community and institutions of connection and belonging.

Instead, we will deal with what research can tell us about two specific consequences of technology that are critical to understanding the path forward for those of us who teach the five-thousand-year-old craft of reading: less reading and shallow reading.

We remind you that these forces affect practically every student and adult, regardless of whether they have a phone, and often regardless of their individual behavior in terms of their phone. Reading is a social behavior, something we do as we do in part, at least, because we learn it from others around us and see it reinforced by them. In this way, even students below the (steadily lowering) age-of-first-device are impacted. Are their older siblings shaping their behaviors by curling up with a book like they once might have? Are their parents?

Plus, while the phone is the primary tool technology companies use to fracture attention, the digital world is always encroaching. Think, for example, of when a five-year-old is handed an iPad in response to a bit of restiveness in the ten slow minutes before food arrives at a café, when they might otherwise have been handed a beloved book or been engaged in conversation with their family.

In the classroom—especially the reading classroom—these changes present us with a choice. We can, on the one hand, accede to them, accept that they are inevitable, and try to reduce the attentional and cognitive demands in the classroom in response. We can present text in shorter, simpler formats, and we can use more video and graphic formats too, as the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) has proposed,[17] and as the Harvard professor Hari interviewed had done, replacing written texts as a source of learning and knowledge.

It’s certainly easier in many ways to choose this approach. We could tell ourselves to do the best we can with the students we get–it’s not our responsibility to try to change them. It would be reasonable simply to decide to adapt ourselves to a brave new world.

We are not yet ready to concede, however. There is too much at stake, we think, in accepting a reduction for our young people—and soon enough adults—in the ability to sustain focus and attention in text. We think the idea that only specialists might be able to read, say, Dickens, or the founding documents of our governments, or the journal articles that herald scientific discovery, to be problematic, to say the least. We don’t think that an impulsive body politic that requires instant gratification or is not adept at sustaining attention is a good thing.

We agree with the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat when he wrote that “the humanities need to be proudly reactionary in some way, to push consciously against the digital order in some fashion, to self-consciously separate and make a virtue of the separation.” English or literature classrooms are best positioned to build the conscious alternative to digital society precisely because of the great books that we think ought to form the bulk of our classroom reading material. We’ve spent several hundred years stocking the war chest, so to speak, with great things to read—books that, once engaged, give students the experience of saying “yes” to something other than the digital world. If we give up on books, we give up on the best antidote we may have to the allure of the digital.

Along those lines, we also don’t want to concede because books are a medium that hold a unique key to strengthening attentional skills—one of the gifts that schooling should give to young people. Reading—deeply and with focus—offers not only a privileged form of access to knowledge but a profound form of enjoyment that is unique and, in many ways, more nourishing than more instantly accessed forms of gratification.

What attracts us in the short run—the constant roll of new information and novel stimulation—is not actually what gives us pleasure in the long run. Far more people—yes, even teens—look back at an evening of scrolling or idle watching with more regret than pleasure. You are drawn to it in the moment but waylaid by your own attention: you later wish you’d gone to the gym, practiced the guitar, read a book. You wish you’d accomplished something, true, but also that you had been doing something that felt meaningful afterwards.

In fact, one of the most pleasurable states a human can experience is something called the “flow” state, extensively studied by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Flow state is the mindset you enter into when you lose yourself in a task that interests you. You become less self-conscious, less aware of almost everything else, even the passage of time. It is essentially a state of deep and unbroken attention.

Perhaps you have felt this playing a sport you love or, as Csikszentmihalyi first studied, while engaging in a form of creative expression like playing a musical instrument or drawing.

Flow is gratifying even if it requires effort—perhaps because it requires it. “The more flow you experience the better you feel”[18] notes Hari. And, he adds, “one of the simplest and most common forms of flow that people experience in their lives is reading a book.”

If phones have ruptured our students’ attention spans by rewarding them with brief flashes of shallow pleasure, books can provide an antidote: helping our students retrain their attention spans, with the reward of deeper, longer-lasting pleasure.

The trick, of course, is getting students to pick up and engage with a book for long enough to actually experience this.

This chapter, then, provides a road map for those of us who choose not to give in to reduced attention but to seek to create in our classrooms an environment where we enrich reading. We begin by presenting a key principle that can guide us in how to improve attention and other capacities that are critical to developing young people who regularly engage in sustained and meaningful thought; then we share three ways to enact that principle in the classroom.

We Wire How We Fire

Because our brains wire how we fire, how we read consistently affects our neurological capacity for future reading. This means we can shape students’ reading experiences in classrooms, taking advantage of the social nature of reading, to develop our students into more attentive and deeper readers—and ones who enjoy it more. .

We begin with the most important phrase in this chapter: We wire how we fire.[19]

The brain is plastic. As we noted in chapter 1, the act of reading is a rewiring of portions of the cortex originally intended for other functions. We are already re-wiring when we read, and how we read shapes how that wiring happens, how we can, and probably will, read.

If we read in a state of constant half-attention, indulging and anticipating distractions, and therefore always standing slightly outside the world a text offers us, our brains learn that is what reading is—they wire for a liminal, fractured state in which we only partially think about the protagonist and his dilemma or the meaning embedded in the Founding Fathers’ chosen syntax.

But thankfully that key phrase, we wire how we fire, cuts both ways. If we build a habit in which reading is done with focus and concentration and even, to go a step further, with empathy and connectedness, and if we do that regularly for a sustained period of time, our brains will get better at reading that way—more familiar with and attuned to such attentional states. We are likely to do less searching for distraction and novel stimulus as we read. We’re also less likely to drift on the surface of a text, but instead to read deeply and to comprehend more fully. And because we are understanding better and are less distracted, we are more likely to persist.

In other words, we can re-build attention and empathy in part by causing students to engage in stretches of sustained and fully engaged reading. One thing this implies is more actual reading in the classroom with more attention paid by teachers to HOW that reading unfolds. Attending to how we read—thinking of the reading we do in the classroom as “wiring”—gives us an opportunity to shape the reading experience intentionally for students. Those who read better, richer, more gratifyingly, more meaningfully, more socially, will read more and get more out of what they read.

A colleague of ours advised—a few years ago and with the best of intentions—that there should be very little actual reading in English classrooms. “The reading happens at home and the classroom is about discussion,” he opined. We love discussion and see plenty of room for it in the classroom, but we think text-centered reading classrooms are strong ones. Our argument then is more urgent now. We are for making the text itself and the act of reading central to the daily life of classroom. Even if we weren’t at a time when it’s clear that without classroom reading, very little reading is done at all, we would still advocate for this practice. We think the science supports us.

Reading with students in the classroom allows us to shape the experience cognitively and socially. We can ensure blocks of sustained focus and that students connect with each other through the shared experience of the story.

[1] In fact they were serialized- meaning that they were—like a Netflix series—released in installments that occasionally dragged out the plot and caused readers to yearn for the next part to arrive.

[2] Theologian Adam Kotsko. https://slate.com/human-interest/2024/02/literacy-crisis-reading-comprehension-college.html

[3] https://www.chronicle.com/article/are-you-assigning-too-much-reading-or-just-too-much-boring-reading/?emailConfirmed=true&supportSignUp=true&supportForgotPassword=true&email=tracey.a.marin%40gmail.com&success=true&code=success&bc_nonce=zy1muzvqybjwk008rf3wa

[5] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/

8] [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-36256-4.

[9] The presence of smartphones—even unused–may “impair cognitive performance by affecting the allocation of attentional resources, even when consumers successfully resist the urge to multitask, mind-wander, or otherwise (consciously) attend to their phones—that is, when their phones are merely present. Despite the frequency with which individuals use their smartphones, we note that these devices are quite often present but not in use—and that the attractiveness of these high-priority stimuli should predict not just their ability to capture the orientation of attention, but also the cognitive costs associated with inhibiting this automatic attention response.” https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/691462

[10] Another attribute of Twenge’s survey instrument is that she and colleagues ask students about behaviors and attitudes across a wide spectrum of topics so questions about reading are embedded among questions about a dozen other topics. Most studies of reading behaviors rely on self-report—necessarily—and so if students, who mostly know they ‘should read more’ know they are primarily being surveyed about their reading behaviors, specifically, they’re perhaps more likely to round up a bit—they know they really should be doing more of it.

[11] “almost everyday”… see iGen https://www.amazon.com/iGen-Super-Connected-Rebellious-Happy-Adulthood/dp/1501151983

[12] See Doug and his co-author’s discussion in Reconnect of the near doubling of screen time among teenagers during and post-pandemic.

[13] https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx If you’re wondering, the data on reading for adults over 15 was 15.6 minutes a day (in 2018). That number was down 28% in just 15 years. It was almost 22 minutes per day in 2003.

[14] https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ltt/reading/student-experiences/?age=13

[15] Someone somewhere is wondering about their child’s capacity to sustain a state of obsessive attention while playing video games. Isn’t this driving him (he is statistically highly likely to be male) to build his attentional capacity? It is not—at least not to low-stimulus events. He is learning to lose himself in a world that constantly offers maximum immediate stimulation and gratification. If you wish for him to sustain attention while reading a medical chart, a novel of historical importance or the Constitution of the United States, you will be disappointed.

[17] Shamefully, we think, they have come out in favor of “decentering the text”: “The time has come to decenter book reading and essay writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education,” they wrote in a recent position statement. “It behooves our profession, as stewards of the communication arts, to confront and challenge the tacit and implicit ways in which print media is valorized.” By contrast, we think it’s actually the job of teachers to valorize reading and writing.

[18] Stolen Focus 57

[19] Adaptation of the phrase “neurons that fire together wire together” coined by the Neuropsychologist Donald Hebb in 1949