This story was updated on Oct. 18 to include comments from districts and on Oct. 25 to describe kindergarten absentee data as including students enrolled in transitional kindergarten.

In the second year fully back in school after remote learning, California school districts made negligible progress overall in reversing the steep declines in test scores that have lingered since Covid struck in 2020.

There was a slight improvement in math while English language arts declined a smidgeon, and the wide proficiency gap between Black and Latino students and whites and Asians showed little change.

Only 34.6% of students met or exceeded standards on the Smarter Balanced math test in 2023, which is 1.2 percentage points higher than a year ago. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, 39.8% of all students were at grade level. Only 16.9% of Black students, 22.7% of Latino students, and 9.9% of English learners were at grade level in 2023.

Year-over-year scores in English language arts dropped less than 1 percentage point to 46.7% for students meeting or exceeding standards in 2023; in 2019, it was 51.7%. The large proficiency gaps between Black and Hispanic students compared with Asian and white students showed little change. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, about 4 in 10 students in the state and 3 out of 4 Asian students, the highest-scoring student group, were at grade level in English language arts.

Among the state’s nearly 1,000 districts, small districts tended to show more gains, results show.

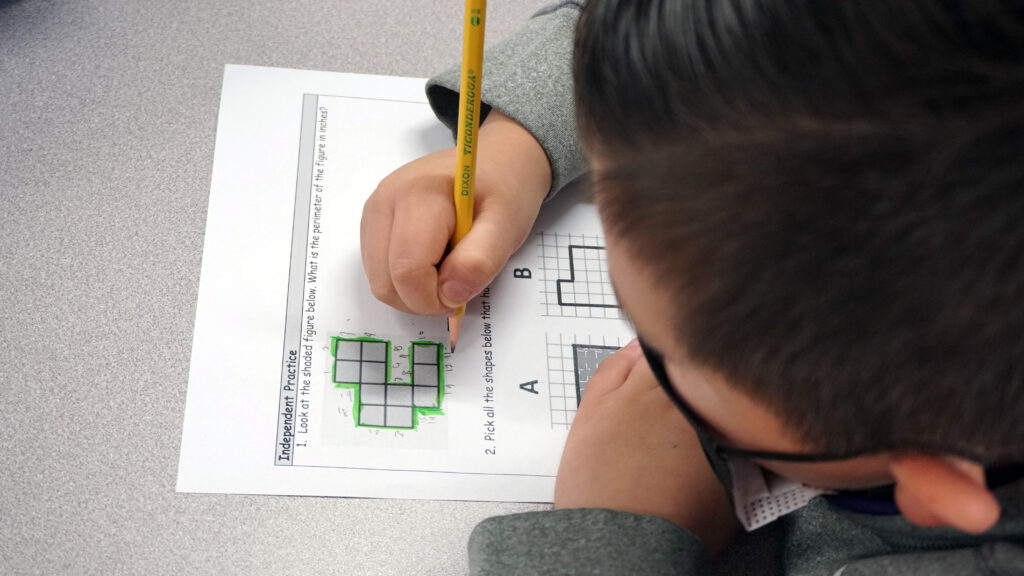

Smarter Balanced tests are given to students in grades three to eight and grade 11.

English language arts scores dropped slightly in every grade except 11th and third grades, which showed slight growth. The 0.8% percentage point increase in third grade may reflect that students had two years of face-to-face instruction, which is critical for learning how to read. It could also reflect concerted efforts to focus on and change reading instruction to phonics-focused curriculums in districts like Long Beach, up 4.1 points over 2022 for all third graders, and Palo Alto, where reading scores for low-income Latino students increased 47 percentage points above pre-pandemic levels.

Fewer English learners met or exceeded standards in English language arts this year. In 2023, 10.9% of English learners met or exceeded the standard for English language arts, down from 12.5% in 2022. Among students who were ever English learners, including those who are now proficient, 35.7% met or exceeded the standard in English language arts, down from 36.5% in 2022.

In math, English learners were about the same as last year, with 9.9% meeting or exceeding the standard. Among those who were ever English learners, including those who are now proficient, 24.2% met or exceeded the standard, up from 23.4% in 2021-22.

A slightly larger share of English learners achieved a proficient score this year on the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC): 16.5%. Students who speak a language other than English at home are required to take the ELPAC every year until they are proficient in English.

Shelly Spiegel-Coleman, strategic adviser to Californians Together, an organization that advocates for English learners, said the fact that a higher percentage of English learners are not achieving proficiency each year shows that California needs to invest more in training teachers in how to help students improve their English language skills, especially within other classes.

“That’s when we see a big bump in students’ language proficiency — when they’re using language to learn about something, when their language development is taught while they’re learning science, while they’re learning social studies, while they’re doing art,” Spiegel-Coleman said. “There’s been no major funding and no major effort to do this kind of work. It’s time now.”

Shifting demographics

In its news release, the California Department of Education stressed that over the past year, the proportion of low-income students statewide rose from 60% to 63% of all students and the increase in homeless students who took the test by 2,000 to 94,000, the equivalent of the third-largest district in California.

Given “the relationship between student advantage and achievement, California’s statewide scores are particularly promising as the proportion of high-need students has also increased in California schools,” the department said.

Christopher Nellum, executive director of The Education Trust–West, an advocacy organization, viewed the results differently.“Seeing only slight improvements in already alarmingly low levels of student achievement is cause for concern, not celebration. In recent years, as in this year’s results, the state’s progress on student outcomes in English and math has been marginal at best. In fact, at no point in the past 9 years have we seen more than 1 out of 5 Black students at grade level in math.

“This trend is an indictment not of the efforts of California’s K-12 students but of the efforts and choices of the state’s adult decision-makers,” he said in a statement.

Mark Rosenbaum, lead attorney for the public interest law firm Public Counsel, cited the lack of improvement as further evidence of why it sued the State Board of Education, the California Department of Education and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, charging the state mishandled remote learning and failed to remedy the harm caused to low-income and minority students.

The latest test results, he said, “are as unsurprising as they are disappointing. What they mean is that California’s most disadvantaged students are falling further and further behind their more affluent counterparts, in large part because the state failed to assure the delivery of remote instruction to their communities during the pandemic and compounded that failure by failing to assure meaningful remediation once schools reopened.”

Cayla J. v. the State of California, is set for trial in December in Alameda County Superior Court.

The latest test statewide results will disappoint others who had hoped to appreciably reclaim some of the lost academic ground. That has not happened in California or in neighboring states that also give the Smarter Balanced assessment. In Oregon, English language arts scores also fell less than 1 percentage point to 43% proficient, and math scores increased less than point to 31.6%. In Washington, it was the same story: English language arts scores were flat at 48.8% while math scores rose 1.8 percentage points to 40.8%.

A handful of states reached pre-pandemic levels on their state tests. They include Iowa and Mississippi in both reading and math, and Tennessee, which created a statewide tutoring program in reading, according to the COVID-19 School Data Hub, an effort led by Brown University economics professor Emily Oster.

Before Covid struck, changes in California’s test scores occurred slowly, a percentage point or two annually, said Heather Hough, executive director of PACE, a Stanford-based education research organization. “It took years of dedicated effort, with investments in education and the workforce, with steady increases in achievement over time, and then we had this huge drop. We can’t afford another 10- to 20-year period of slow incremental change, especially when what we know we’re facing is huge inequities in student achievement,” she said. “We have to keep that intensity that we have not fixed this problem, despite investments and despite good intentions.”

Los Angeles Unified, the state’s largest district with 429,000 students, is representative of where most districts are. It has seen widespread improvement in math scores across most grade levels, with 30.5% of students meeting or exceeding state standards. Its English language arts scores have been a “mixed bag,” said district Superintendent Alberto Carvalho at Tuesday’s board meeting. Forty-one percent of students in the district met or exceeded standards in English language arts – a drop of less than point from the past year.

Carvalho said he was pleased to see third- and fourth-grade English language arts scores moving in the “right direction” — but stressed the need for improvement among upper elementary grades and middle schools. The district has found small-group instruction and “high dosage tutoring” to be critical, and hopes changes to the district’s Primary Promise program will help, he said.

Infusion of funding

California school districts received record levels of one-time and ongoing funding since the start of Covid and had wide discretion on how to use it. This includes the last $12.5 billion in federal pandemic relief, which districts must spend by next September. At least 20% must be spent on learning recovery.

Some districts, mainly small ones, saw double-digit gains in 2023. Escondido Union High School District in San Diego County, with 7,000 students, saw its English language arts proficiency rise from 43.5% to 53.7%. The 800-student Wheatland Union High School District in Yuba County raised its proficiency level in English language arts by 21.5 percentage points, to 60%; its math scores rose 13.3 percentage points to nearly the state average for meeting state standards. Math scores in Healdsburg Unified in Sonoma County, with 1,200 students, rose 11.9 percentage points to 39.3% at grade level.

But in most districts, record student absences and staff shortages — not only among STEM and special education teachers but also vacant positions for aides and counselors and unfilled jobs for substitute teachers — undermine strategies for recovery. And the problems linger.

Stubbornly high chronic absences

Along with test scores, the state released chronic absenteeism data on Wednesday showing nearly a quarter of all students chronically absent in 2023, double the 12.1% rate in 2019.

While the 2023 chronic absenteeism rate is high, it’s a drop from 2022, which saw an unprecedented high rate of nearly a third. Students are counted as chronically absent for missing 10% or more of school days. The rates of the state’s minority groups and most vulnerable students remain disproportionately high: 34.6% for students with disabilities, 40.6% for homeless youths and 28.1% for English learners.

“The staffing has been a huge struggle for us, but so has absenteeism,” said Rick Miller, chief executive officer of the CORE districts, a school improvement organization that works with eight urban districts, including Los Angeles, Long Beach, Fresno and Sacramento City. “There was the notion that kids go to school every day. The pandemic changed that. And there’s a mindset we’re working through that you don’t need to be in school every day. You be there when you can.”

That appears to be the case in kindergarten, where the chronic absenteeism rate was 40.4% in 2021-22 and 36.3% in 2022-23, compared with 15.6% in 2018-19. Unlike many states, California includes excused absences in its chronic absentee rate calculations. The kindergarten data includes students enrolled in transitional kindergarten, a program for 4-year-olds whose 5th birthday will fall between Sept. 2 and April 2.

Other factors are working against student learning, PACE’s Hough said. At the same time, teachers need to accelerate learning, they are backfilling the needs of absent students. Some students come to school with mental health issues or lack socialization. Political disputes at school board meetings are diverting attention from districts’ learning priorities.

“The basic work of educating kids and running school districts has gotten a lot more complicated,” she said.

Amy Slavensky, interim deputy superintendent of San Juan Unified, agreed. “When you’re in schools every day, or nearly every day like we are, we can see the direct impact of that on our students,” she said. “It’s just not the same as it was before. So it’s going to take time.”

San Juan Unified, in Sacramento County, has sharply increased training for teachers, added intervention teachers and improved attendance at its schools, but its students’ test scores still have not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

Nearly 42% of the 49,000 students met or exceeded state standards in English language arts in 2023, down about 1 percentage point from 2022. Math scores were stagnant with 29.6% meeting or exceeding state standards, down 7.5 percentage points from 2019.

The district has used multiple tactics to increase achievement, including hiring intervention teachers and expanding training for teachers in reading and math. The district is training grade-level cohorts of teachers using some of the latest research to strengthen their strategies around reading instruction, Slavensky said. The district is seeing gains in kindergarten and first grade at Dyer-Kelly Elementary School, which has been focusing intensely on early literacy, she said.

“Anytime you implement a new change initiative, it takes four or five years to really see the impact of that, and especially on a summative assessment like CAASPP,” Slavensky said.

To increase math scores, the district is also adding math sections in middle and high school master schedules to reduce class sizes so teachers can offer deeper instruction and differentiated instruction, Slavensky said.

But pulling dozens of teachers out of their classrooms for training isn’t always possible during a teacher shortage, said Superintendent Melissa Bassanelli. Training schedules often fall apart when there aren’t enough teachers to fill the classrooms.

Garden Grove Unified in Orange County, with 79% low-income students and 94% students of color, has scored well above state averages on Smarter Balanced tests and ranks highest among the CORE districts, but saw its math scores fall 7.5 percentage points from pre-pandemic 2019. In 2023, it clawed back half of the difference, though it wasn’t easy, Superintendent Gabriela Mafi said. Many families still struggled financially; resurgent Covid kept students at home; and a lack of subs strained schools.

But Garden Grove, a highly centralized district, stayed true to its system of deploying teacher coaches to schools and encouraging conversations around math concepts in elementary grades. It is using extended learning time at Boys and Girls Clubs and summer programs for academic interventions and supports, Mafi said. “We haven’t quite rebounded to our pre-Covid, but we’re getting close,” she said.

Perhaps no district high-achieving in math took a bigger hit to its Smarter Balanced scores than Rocketship Public Schools, a network with 13 K-5 Title I charter schools in the Bay Area. In 2018-19, 60% of students were at or above standard. By 2021-22, the proficiency rate, while still above the state average, had fallen to 40%. In 2023, overall scores increased by 2 percentage points with variations among schools.

Recovery will entail a multipronged, multiyear strategy, said Danny Echeverry, Rocketship’s Bay Area director of schools. It started with using its community schools funding to hire a Care Corps worker, akin to a social worker, at each site to help families who experienced housing and food insecurity during Covid. “We’ve seen ourselves as a hub of connecting at-risk families with social services in the community,” he said. Chronic absenteeism fell 10 percentage points, and attendance increased 7 percentage points in 2022-23.

Students in kindergarten, first grade or second grade during the pandemic had foundational skill gaps that had to be filled before students could handle grade-level content and move to proficiency on state tests, Etcheverry said. The Rocketship model builds in flex time so that teachers can provide one-on-one interventions.

Scores increased 2 percentage points overall on the 2023 math test, with variations among schools from a decline of 7.4 percentage points to a gain of 15.8 percentage points. Rocketship Los Sueños in San Jose, which piloted the Eureka Math curriculum, gained 5.4 percentage points in 2023, leading to a decision to adopt it in all Bay Area schools.

“We’re building traction, and we have no reason to believe that we’re not going to continue that momentum and see greater gains this year,” Etcheverry said.

Twin Rivers Unified, in Sacramento, made incremental gains this year but still has a long way to go before catching up to 2019 scores. More than 80% of the students are from low-income families.

“Our scores might be below the state average, but our growth is ahead in both English and math,” said Lori Grace, associate superintendent of school leadership.

In 2023, 31.9% of its students met or exceeded state standards in English language arts, up 0.5 points from 2022. In math, 22.7% of the district’s students met or exceeded state standards, an increase of 2.7 points. In 2019, 37% of students were proficient in English language arts and 29% in math.

To combat pandemic-related learning loss, the district added a multitiered system of support at schools, a framework that gives targeted support to struggling students, Grace said. To improve literacy skills, the district began a reading intervention program focusing on the science of reading for kindergarten through third grade. The district also tapped its best teachers to offer coaching on the subject to fourth through sixth grade teachers.

Central Valley strategies

Most students in Fresno Unified, the state’s third-largest school district with over 70,000 students, are not meeting standards. Last year, 33.2% of Fresno Unified students met or exceeded English language arts standards, a 1 percentage point gain from a year ago. In math, 23.3% met or exceeded state standards, a 2.5 point increase.

“We are definitely not satisfied with our results,” said Zerina Hargrove, the Fresno Unified assistant superintendent of research, evaluation and assessment. “While we had many students grow in their achievement, we had just as many who slid backward, contributing to very little change overall.”

Fresno Unified plans to focus on ensuring that every child shows growth, specifically targeting the needs of historically underserved student groups, Hargrove said.

One way to do that is by evaluating the “shining stars,” the schools that made significant progress. For example, at Jefferson Elementary, 6.9% more students met or exceeded standards in English, and 15.6% more students met or exceeded math standards. At Bullard High School, 17.6% more students met or exceeded English standards; at Patiño School of Entrepreneurship, 27.5% more students met or exceeded math standards.

“We desire to learn from the schools that have made significant gains and dig deeper into the why of those who didn’t,” she said.

Fresno Unified’s neighbor, Clovis Unified, has some of the highest student achievement scores in the area.

With more than 40,000 students, 72.7% were at or above state standards for English language arts in 2019. By 2022, that percentage dropped to 66.2% and remained flat in 2023. In 2019, 58.7% of Clovis Unified’s students met or exceeded math standards, and in 2022, 49.3% did so. The nearly 2 percentage-point growth in math in 2023 puts the proficiency level at more than 51%.

Still, the numbers haven’t returned to their pre-pandemic proficiency levels.

“Some of our schools saw student achievement grow by anywhere from 15 to 22% at certain grade levels. We must now work together to replicate that level of achievement across every grade level and school in our district,” said Superintendent Corrine Folmer.

The pandemic’s impact persists, district spokesperson Kelly Avants said, citing continuing challenges to learning. They include, she said, “restoring classroom behavior expectations; re-developing the interpersonal relationships between students and between students and their teachers that equates to success in the classroom and facing the impact of decreases in attendance rates has on learning.”

EdSource reporters also contributed to this report: Diana Lambert, Lasherica Thornton, Mallika Seshadri and Zaidee Stavely.