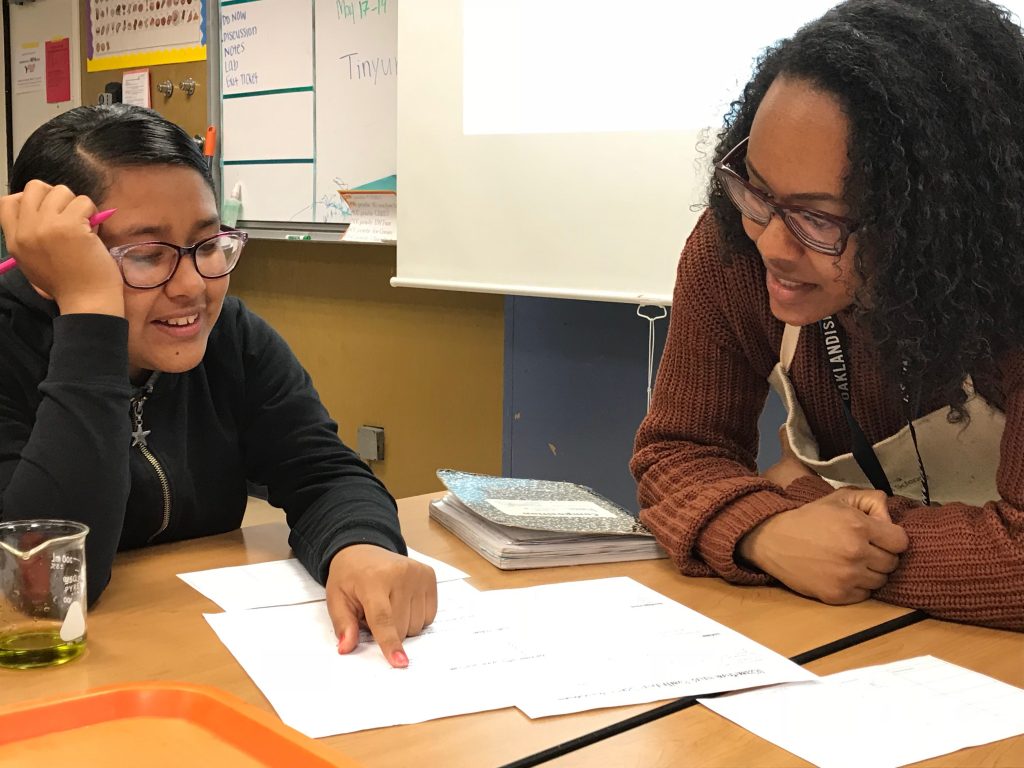

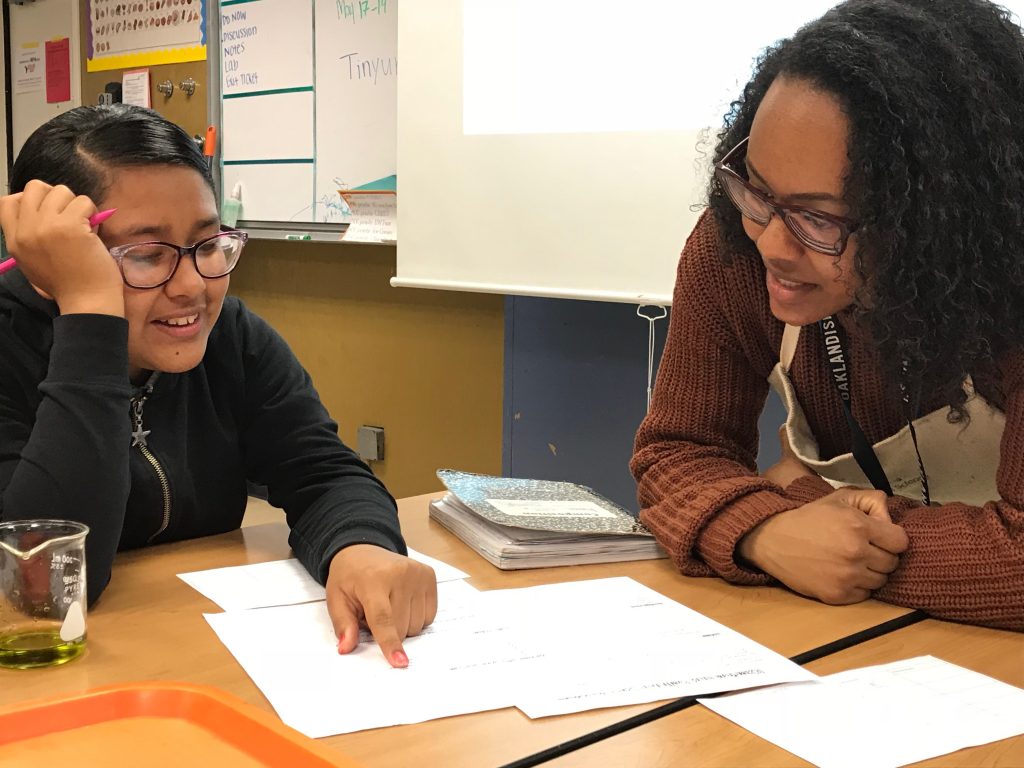

Lauren Brown teaches seventh grade science at Madison Park Business and Arts Academy in Oakland.

Credit: Carolyn Jones/EdSource

More often than not, people perform up to what’s expected of them. It’s why goal setting is such an effective way to self-motivate as well as motivate others. It’s widely called the Pygmalion effect, and it’s been proven in education repeatedly. A Center for American Progress study run from 2002-2012, following students throughout their learning journeys, found that 10th grade students faced with higher goals and expectations from their teachers were three times more likely to graduate from college than peers who had not been challenged with the same expectations.

In order to set students and classrooms up for success, teachers must empower students by not only showing them what’s possible, but even more important, showing them the steps needed to get there. This second part is essential when creating positive, inclusive learning environments and advancing educational equity.

GoGuardian’s 2022-2023 State of Engagement Report, which was conducted in collaboration with the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education Center EDGE, found that 94.2% of teachers reported using high expectation setting as an engagement strategy often or very often, laying out stretch goals and holding students to a high classroom standard. Setting high expectations can improve educational equity by showing students what is possible.

Unfortunately, in the same Center for American Progress study, researchers found that secondary school teachers often had lower expectations of students of disadvantaged backgrounds. In fact, teachers predicted high-poverty students to be 53% less likely to graduate from college, which, when combined with the data proving students’ success is closely tied to the expectations teachers set for them, likely contributes to a cyclical problem.

Education can be a great equalizer. But it’s common for students who have experienced poverty or who have faced other institutional academic (or non-academic) challenges to have never been told they can achieve great things. Setting clear and high expectations for students can change that. If students haven’t been introduced to the idea of a growth mindset, it can be challenging to suddenly place goals in front of them, But doing so is fundamental to helping students learn to set their own academic goals. If we zoom out, it’s also the first step in building an equitable and inclusive classroom environment.

Research has shown personalized goal setting — where students track their own goals and determine their own progress — is a huge step in “self-regulated learning.” Setting personalized goals results in students having significant investment in their own learning and personalized goals. A recent study of 5 million K-eight students across the country found students who entered a school year “behind” grade level were more likely to catch up when set up with “aggressive” or “stretch” goals.

The challenge lies in ensuring students see their goals as growth-oriented rather than unreachable or even punitive. Especially when working with students who come from lower socio-economic environments, it’s essential that educators proactively articulate (and remind) students that what they’re asking is possible. Students also need to understand the why and the how behind the goals. Setting a goal and walking away without providing a road map is not a strong strategy, and will prove especially confusing for students who aren’t used to facing high expectations.

Humanizing expectations is extremely impactful. Students won’t achieve a goal if they don’t understand why they’re doing something. We must push students to do things that they may not even know they’re capable of, even as we keep in mind the ultimate goal of equipping them to go into the world, enabling them to compete and make the world a better place. That comes by expanding your world, being curious, and being in an environment where intellectual curiosity is supported. That originates with teachers showing each of their students that they are capable, and building equitable environments where all students can thrive.

Ultimately, teachers, educators and other education professionals need to walk the walk when it comes to goal setting and improving equity. Implicit bias is real and cannot be ignored. Teachers and administrators need to be actively aware of their own biases and actively work to mitigate them on an ongoing basis.

Setting high expectations also requires that teachers really understand their students, have established and nurtured relationships with them, and have demonstrated they care about all students and the unique challenges they face. Knowing what is going on with students outside of school is a key ingredient to effective goal setting. What do they have going on that may impact their ability to be all-in academically? This is perhaps the most essential step in building an inclusive learning environment.

Education technology, especially tools built with participation or collaboration at the heart, can aid in this process by helping teachers not only personalize learning, but also help streamline data analysis that can assist in setting goals that make sense, that are achievable, but that also stretch students outside their comfort zones and move learning outcomes forward. Meeting every student’s needs is required for building educational equity. Educational technologies are often developed to do just that, supporting teachers as they work to individualize learning in a time when they are underpaid, overworked and still motivated to meet students where they are.

Telling students you believe in them is wonderful. But showing them you believe in them — through high expectations and accountability — means you are preparing them for greatness.

•••

Dionna Smith is the chief diversity and public affairs officer at GoGuardian, an educational technology company that aims to help all learners feel ready and inspired to solve the world’s greatest challenges by combining the best in learning and science technology across every part of the learning journey.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.