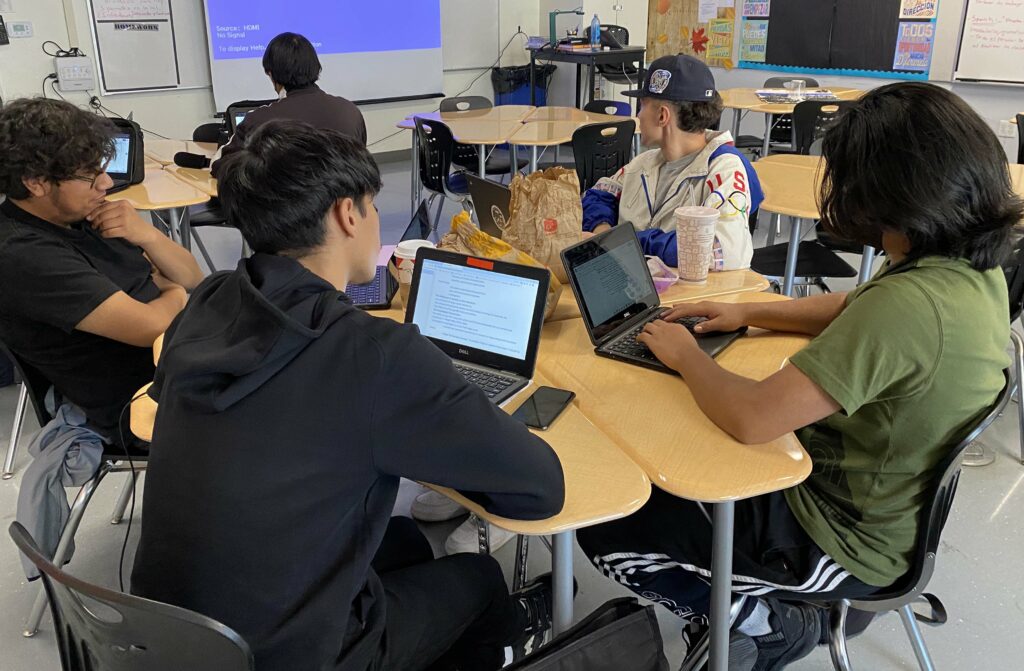

Fresno City College campus.

Credit: Ashleigh Panoo/EdSource

Creating a more streamlined transfer pathway and expanding initiatives such as dual enrollment and dual admissions could help increase the number of California students who successfully transfer from community college to a university, officials from the state’s public higher education segments said Tuesday.

“The key is that across all three of our systems, that we have a more unified process for designing pathways and programs together … so that these pathways naturally flow from the community college system into the CSU, into the UC,” Aisha Lowe, an executive vice chancellor for California’s community college system, said during a panel discussion hosted by the Public Policy Institute of California.

The panel, which also included representatives from the University of California and California State University systems, came on the heels of a PPIC report that found that few students who wish to transfer from a community college to a UC or Cal State campus are successful in doing so.

The report also found that there are big racial and regional disparities in transfer students. For example, Black and Latino students as well as students from the San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire are less likely than their peers to transfer successfully.

But the state is taking steps that officials expect will improve the transfer process, which critics say is overly complex. Students considering transferring to a UC or Cal State often have to contend with different course requirements, depending on the campus, even in the same major.

Currently, top lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom are in agreement on the framework of a new pilot transfer program between the community colleges and UC, Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, D-Sacramento, told EdSource on Monday. Under Assembly Bill 1291, transfer students earning an associate degree for transfer would get priority admission, first to UCLA in select majors and later to additional campuses. Proponents say that solution will help streamline the transfer process because students earning an associate degree for transfer can already get a guaranteed spot in the Cal State system.

UC has not yet formally endorsed the new bill, but McCarty said UC was involved in the negotiations that resulted in the legislation.

Yvette Gullatt, UC’s vice president for graduate and undergraduate affairs, said during Tuesday’s panel that UC sees the associate degree for transfer “as an opportunity to enhance transfer, particularly” at community colleges where few students successfully transfer.

“There’s always opportunity to explore more ways that ADTs can benefit students at UC, and you’ll hear more from us soon about some ways we plan to do that,” she added.

California is also in the process of expanding both dual enrollment, in which high school students take college courses, and dual admission programs, which guarantee high school graduates a future spot at a UC or Cal State after they first attend a community college.

The new statewide chancellor for the community college system, Sonya Christian, has said she wants every ninth grader to enroll in a college course through dual enrollment.

Lowe said Christian’s plan could help improve the likelihood that students eventually attend a community college and transfer to a UC or Cal State campus by “getting them on that pathway” earlier in their academic career.

“Helping them to get some of their transfer requirements done while they’re still in high school, exposing them to financial aid and the FAFSA and that process while they’re still in high school,” she added. “So we’re working on rolling out a comprehensive program around dual enrollment because we think that that’s going to continue to be an important lever.”

At the same time, new pilot programs in dual admission at both UC and Cal State are going into effect this fall. The programs are open to students who weren’t admitted to the system where they are applying for dual admission. Both segments will guarantee eligible students a spot in their chosen major and at their chosen campus, so long as they meet all their requirements. Not all majors are available and, in the case of UC, not all campuses are participating. More information about the programs can be found here for UC and here for Cal State.

Laura Massa, interim associate vice chancellor at Cal State, said during Tuesday’s panel that about 2,500 prospective students already have created an account on the portal for that system’s dual admissions program.

Dual admission has the potential to be a “very promising practice,” said Marisol Cuellar Mejia, one of the authors of the PPIC report and moderator of Tuesday’s panel, in an interview.

“It makes things more streamlined because from the beginning you know exactly where you are going, and then you avoid any duplication of courses or anything like that,” she said. “We are curious to see what it’s going to look like with these pilots.”