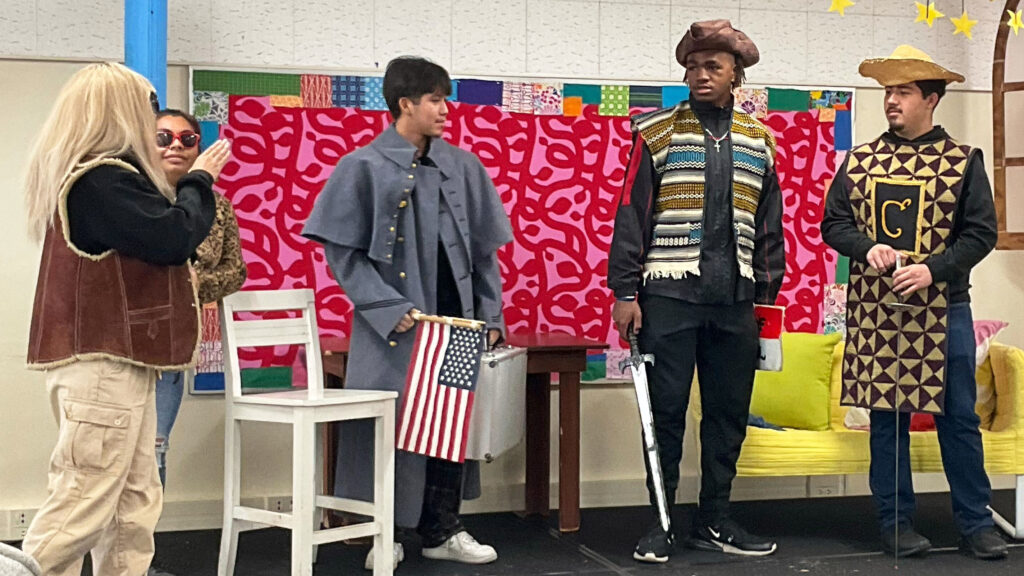

Catherine Borek’s drama class working on a scene.

Credit: Courtesy of Catherine Borek

Catherine Borek first came to Compton’s Dominguez High School intending to spend a few years with Teach for America before becoming a professor. That was 29 years ago. Hired to teach AP English literature, the newbie teacher quickly jumped into the fray as a drama teacher as well.

A theater kid back in high school, she knew instinctively she needed to bring classical texts to life for her students by lifting the words off the page and into the spotlight. The experience has changed her life and the lives of many of her students.

“You find yourself when you’re up on that stage,” said Borek, a tireless educator who was named a California Teacher of the Year in 2023.

Alas, there was no stage, no rehearsal space and no fundraising. All she had going for her was chutzpah. The cash-strapped school had not put on a play in 20 years. That’s when Borek discovered her “MacGyver mode.”

“You take what you have, and you make something out of that,” said the 50-year-old mother of two. “We put on plays; we put on operas; we put on poetry slams.”

The unstoppable teacher can make theater magic happen in a computer lab. She can put on a show without a cent from the school budget. She can get teenagers to put their phones away and enjoy being social. She helps them ignite the ingenuity in each other.

“There’s something about creativity that’s almost religious to me,” as she puts it. “It’s the space to almost be divine, you know? And we use theater to get us there.”

Borek joined Teach for America — a nonprofit that recruits graduates from top universities to serve at least two years teaching in low-income schools — right out of Reed College. She had intended to be a teacher only temporarily, but quickly fell in love with her vocation.

She believes that students from the hardscrabble Compton district, a place where gunshots are as much a part of the environment as graduation, deserve every bit as much cultural enrichment as children of privilege. She often refers to her students as “scholars,” preferring to discuss their merits instead of her own.

“It lifts you up,” she said with customary modesty. “The students have a different energy here. They’re so gung-ho and excited and enthusiastic that it helps dispel some of the melancholy that we see around the world right now.”

That’s why, over the years, she has empowered her students to be cultural ambassadors, combating long-held stereotypes of Compton. They have completed the LA Marathon, collaborated with the LA Opera, made it to the regional level of the Poetry Out Loud competition, starred in a Keurig commercial and started a rugby club. A 2003 documentary about Borek’s first class play, “OT: Our Town,” a staging of the Thorton Wilder famous paean to small-town life, captures the raucous creativity of a student ensemble tackling a masterpiece on a makeshift stage in the cafeteria.

In that documentary, Ebony Star Norwood-Brown, the 16-year-old playing the narrator, wryly noted that the arts is one way to battle tired “Boyz n the Hood” tropes.

“Compton is home of gangster rap and gangsters,” said Norwood-Brown. “That’s all people know about Compton. That’s all people think about Compton. … We’re way different from what you think we are.”

Drama has also become an antidote to a world dominated by screens where teens sometimes miss out on the magic of human connection, the bond between students and teachers that can make a lesson spark. Fist bumps and check-ins are part of her curriculum.

“One of the most heartbreaking parts of the pandemic is that we became an online learning community instead of a human, face-to-face learning community,” she said wistfully. “Pre-pandemic, it wasn’t quite as sedentary, and I don’t remember computers being the No. 1 source of knowledge and information.”

Borek prefers to frame learning as a cathartic experience, so that lessons resonate more deeply amid our short-attention span culture. She once had her class, a generation scarred by the pandemic, make scary movies to help them confront their fears.

“Borek’s approach to instruction and lesson building is a reminder of what the last few years have demonstrated to be most important in education: people and the bodies we occupy,” said Caleb Oliver, principal of Dominguez. “When technology fails and funds are low, these endure as the conduit to learning that has stood the test of time. We learn best through action and others.”

The veteran teacher soon realized that many of her students needed drama, not just to become more creative, but also to help them cope with the pressing mental health issues that mark their generation. This is theater as exposure therapy.

“While so many of our students are struggling with anxiety and depression, theater is one of the best forms of therapy,” she said. “It offers exposure bit by bit. We expose them to good stress, and we help them strengthen their wings so that they can fly.”

She recalls one student so paralyzed by anxiety that he couldn’t even get up onstage when he started. He wanted to drop the class. But she convinced him to stick with it until he could stand his ground in the spotlight.

“Communication, teamwork and a positive attitude are among the skills that we strive to leave our students with to be ready for college and the workplace,” Oliver said. “Borek’s students always return years later crediting her with igniting these skills within them in her class.”

Two other students, new immigrants, were shy because they didn’t speak much English and felt awkward with their peers. During the semester, they became emboldened enough to perform a poem onstage.

“They worked together not just to say the poem, but to become the poem,” Borek said. “These words became movements, these young women worked through language barriers to communicate beyond words. That is the power of the arts.”

Drama can also provide an escape valve for students feeling crushed by the stress of trying to get into their dream college amid a sea of valedictorians.

“There’s a lot of pressure on kids in high school right now,” she said. “It’s sort of an unforgiving, relentless punch in the face. And even if parents aren’t telling them they need to be perfect, they’re hearing it from everywhere else. You’ve got to get straight As.”

Feeling overwhelmed by the world can make some young people wall themselves off. Drama can help break down those barriers.

“I honestly do feel like it changed my life,” said Nathalie Reyes, 17. “I used to be super shy, and speaking up in class felt nearly impossible, but drama gave me a space where I could experiment with my voice. It taught me how to take up space, be confident in my ideas, and not overthink every little thing.”

Steeping in the wisdom of the past is one way to shield yourself against the worries of the present. That’s why unlocking the universality of literature is the heart of Borek’s mission.

As the narrator in “Our Town,” puts it: “There’s something way down deep that’s eternal about every human being.”

To her great chagrin, when her English students first read Arthur Miller’s iconic tragedy “Death of a Salesman,” it just didn’t click with them. The trouble was they loathed Willy Loman, the has-been traveling salesman.

Never one to give up easily, Borek took them to see a revival of the play in Burbank. It was a light bulb moment. The production opened their eyes to Miller’s piercing insights into the dark side of the American dream. One of her students even realized that Loman reminded him of his own father. Tears were shed.

“It was gobsmacking for them,” she recalls happily. “I can’t tell you how many students came up to me and they’re like, ‘Man, I related to that, the frustration between that father and son.’ It was their first time at the theater, and they were crying.”