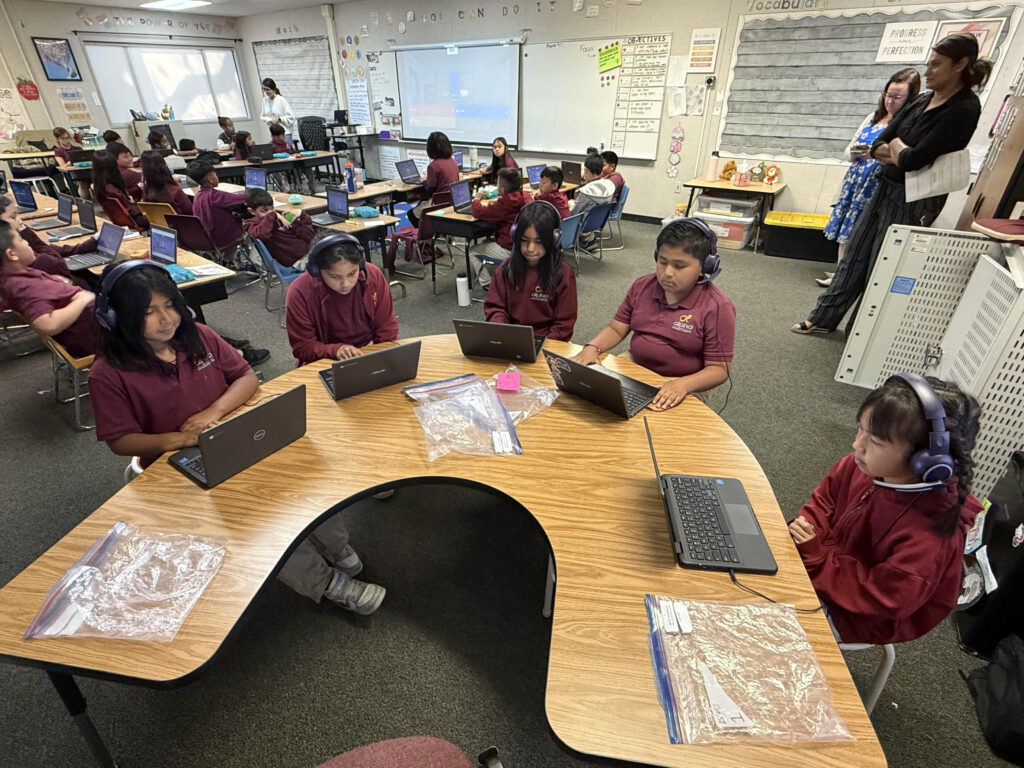

Photo courtesy of Garden Grove Unified

This is the third in a series of stories on the challenges impacting California’s efforts to offer high-quality instruction to all 4-year-olds by 2025.

This past school year, 4-year-old Yoshua would’ve been home, watching TV or playing on his tablet if he hadn’t been enrolled in Garden Grove Unified’s transitional kindergarten (TK) program, according to his mom, Briseida, who asked that her last name not be used.

“Learning the English language, learning how to start writing his name, learning colors and numbers, knowing that he goes to school with his classmates and can talk and play with them, knowing that his teacher will teach him new things,” Briseida said in Spanish in a district video about the importance of TK, an additional year of public education prior to kindergarten. “All of that has been very positive for us because if he had stayed at home, he would not have learned any of those things.”

The large, urban, nearly 40,000-student Garden Grove school community includes immigrants with many families who do not speak English at home. So, those TK students are exposed not only to academic content but also a full year of the English language, said Gabriela Mafi, superintendent of Garden Grove Unified School District, in which English is not the primary language of 63.6% of students.

Sending 4-year-olds to TK benefits students as well as their families. For example, enrollment for Noel allowed his mom, Celeste Monroy, time to seek employment and enroll in classes to learn English, she said in the school district video.

Many parents in the northern Orange County community cannot afford private preschool, which can cost thousands of dollars annually, nor can they accommodate a half-day program, such as many offered by the state’s public preschool programs.

TK has been gradually expanding to reach all the state’s 4-year-olds by the 2025-26 school year, and each school year, more 4-year-olds become eligible.

In 2023-24, children who turned 5 between Sept. 2 and April 2 were eligible. Districts had a choice to even enroll younger 4-year-olds ahead of the phased timeline, such as Noel — who has a birthday after April 2 and would turn 5 by June 30, the end of the school year.

Planning ahead, Garden Grove Unified staffed its classes to comply with the state requirement of 24 students per class size average and a 1:12 adult-child staffing ratio, getting that average to just under 21 students with one teacher and an aide.

Then, the state established new rules just months ahead of the 2023-24 school year.

Such “last-minute changes” at the state level complicate school district operations and impact students locally, superintendents say.

During the budget process in summer 2023, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation creating a new category for kids participating in TK ahead of the state’s timeline, changing the birthday cutoff dates, lowering TK requirements for classes with those students and applying fiscal penalties for noncompliance.

The legislation added an “early enrollment” distinction for 4-year-olds with birthdays after June 2. Students with June 3-30 birthdays were to be considered early enrollment children, requiring stricter guidelines.

Prior to the legislative change, there were no special provisions for the enrollment of students who turned 5 before the school year ended on June 30.

For the 2023-24 and 2024-25 school years, any class with an early enrollment child must meet a 20-student class size maximum and a 1:10 adult-to-student ratio, or face penalties.

Districts were left with a difficult decision for a school year starting in less than two months: Retain the students they’d enrolled and try to comply with the stricter requirements; face penalties if and when they can’t adhere to the more restrictive regulations; or turn away families.

According to superintendents, the state’s last-minute changes illustrate the disconnect between state-level decisions and local implementation and exemplify the state’s lack of understanding of the needs of families, disproportionately impacting districts trying to meet those needs.

“We make commitments to our families and then now have to either undo them or incur something punitive because we tried to serve our communities the best we possibly can,” said John Garcia, superintendent of the 22,000-student Downey Unified, an urban/suburban school district in southeast Los Angeles County.

Why enroll younger students?

The need to offer early childhood education, generally believed to benefit disadvantaged children, was at the heart of Garden Grove and Downey Unified decisions to accept younger cohorts of children for TK sooner than the state’s timeline.

Families in both districts were unable to afford fee-based preschool or work due to a need for child care.

“If he wasn’t given this opportunity to go to TK, he would have either been in day care/preschool, or I would’ve had to quit work and not be able to financially provide for my family,” a Garden Grove Unified parent shared regarding their child for a district document about the impact of TK.

TK not only saves on child care costs that burdened families but, according to educators and experts, also builds a strong educational foundation and bridges the opportunity gap between low-income families and affluent ones — gaps more prevalent in high-poverty districts.

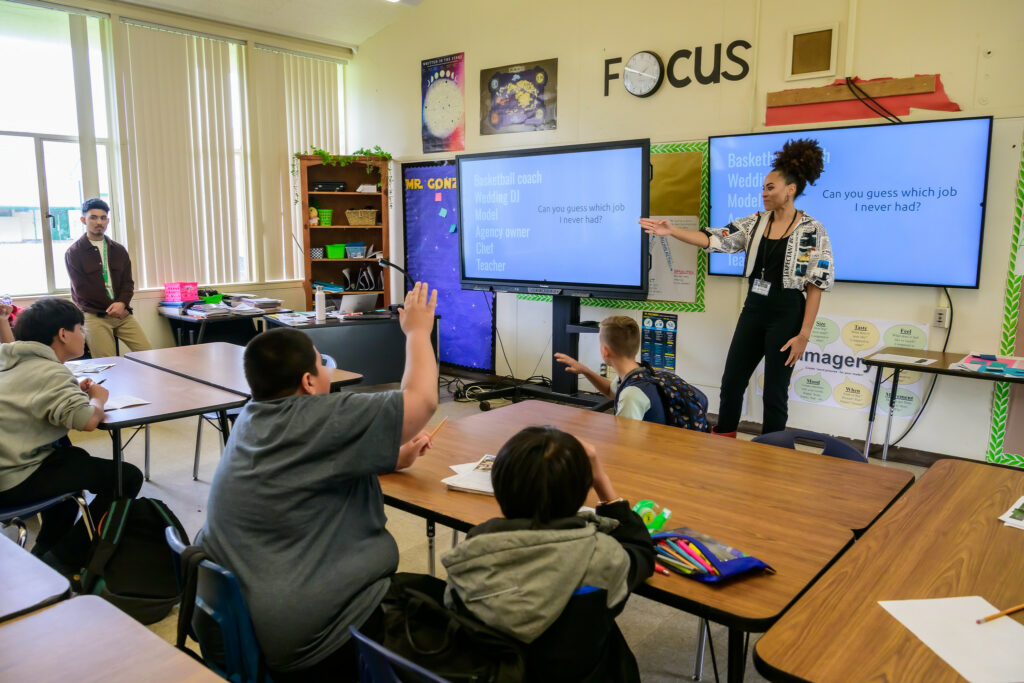

Enrolling younger students sooner meant a full year of instruction before kindergarten, Garcia said, adding that Downey Unified kindergarten teachers notice a difference in those who gain an extra year of schooling.

In high-poverty districts specifically, that additional year gives the kids “an opportunity to have a head start on kindergarten,” Mafi said. “And those are the kids who need it the most, which is why many high-poverty districts chose to accelerate TK faster.”

About 81% of students in Garden Grove and nearly 70% in Downey Unified are classified as low income, based on January data of unduplicated student counts. In contrast, high-wealth districts may not have had the need to offer TK sooner because their families can afford to pay for private preschool, Mafi said.

“This is the message I feel they’re telling us: ‘Poor kids — they don’t need to be helped, to have the same quality of a pre-kindergarten experience like their more affluent peers.’ And I don’t think that’s the message they should be sending.”

Even though low-income students could benefit more from early childhood education, such children have lower preschool enrollment, the Public Policy Institute of California found.

Research shows that high-quality preschool leads to students being prepared for school with improved behavior and learning skills and higher academic performance in math and reading once enrolled, all of which can help bridge the gap between students from high-poverty and high-wealth families.

“All we’re trying to do is address the opportunity gap,” Mafi said.

Trailer bill changed birthday cutoffs, requirements

In July 2021, legislation to expand TK passed, phasing in 4-year-old students until all are eligible by 2025-26.

Based on the 2021 legislation and continued guidance in 2023, districts could enroll TK students ahead of the state’s timeline as long as they turned 5 by the end of the school year, defined as June 30.

January-February 2023: For the 2023-24 school year, many school districts started TK registration, including for students who would turn 5 by June 30, 2024 — a choice aligned with legislation and state guidance available to districts at the time.

There were even younger 4-year-olds with July or August birthdays, who would not turn 5 during the school year and would not be eligible for TK until 2025-26, based on the 2021 legislation.

January 2023: Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget proposed a way to fix that by allowing districts to use local dollars to enroll children with July and August birthdays, “a welcomed proposal” that remained in the May revisions, a Los Angeles Unified spokesperson told EdSource.

June-July 2023: Lawmakers reached a compromise to allow the younger 4-year-old students as long as classrooms adhere to stricter requirements.

July 2023: The governor signed SB 114, an education budget trailer bill, which created lower statutory requirements for the 2023-24 and 2024-25 school years for school districts serving newly-defined “early enrollment” children, 4-year-olds with summer birthdays during and after the school year (from June 3 to Sept. 1).

“We believe that this compromise was vastly preferable to the alternative of disenrolling families, who would have had to scramble for alternative education and care options for their 4-year-old children,” Newsom administration officials said.

San Diego Unified, which had been supportive of efforts to include all 4-year-olds, and Los Angeles Unified were not privy to the compromise between legislative leaders and the Newsom administration, but they were pleased that the result allowed schools to serve students they had already enrolled, spokespersons from the districts said. About 14% of LAUSD TK students have summer birthdays between June 3 and Sept. 1.

Other districts that were enrolling students ahead of the state’s timeline, but within the previous legislation language, had registered students with June 3-30 birthdays.

“It’s that June 3rd to June 30th — that is the date change … making them early enrollment kids,” Mafi said. “No one ever said that before in the last four years.”

The differences are significant

The state’s authorization for the youngest group of TK students came with stricter requirements. Specifically, the 2021 guidelines required a regular TK class to have an average of 24 or less, measured across the school, with an adult-to-student ratio of 1:12. The 2023 rules require a TK class with early enrollment kids to be measured individually and held to a 20-student maximum with a 1:10 ratio.

The stricter ratio for classes with early enrollment kids is more closely aligned with 1:8 staffing practices in early education at licensed child care centers, private preschools and state preschool programs and the 1:10 ratio at Head Start.

But combined with the 20-student max, the requirements exceed guidelines of other programs serving 3- and 4-year-olds, statewide organizations, county education offices and superintendents from LAUSD, Fresno, Oakland, Garden Grove, Downey, Westminster and La Habra City unified school districts said in a March letter.

The California state preschool programs allow class sizes of 24 with a 1:8 ratio, according to the letter, which urged legislators to eliminate penalties and give districts time to reduce ratios for the early enrollment students.

Prior to the 2023 change, students born between April 3 and June 30 were considered regular TK students without different requirements. The trailer bill made those born June 3 to June 30 early enrollment kids.

Garden Grove didn’t disenroll the students, who’d already been promised a spot.

Serving 1,736 TK students, the district had classes with an average of 21 students, well below the 24-student average enrollment requirement for regular TK but above the stricter 20-student requirement for any class with an early enrollment student.

Garden Grove estimated their penalties at around $58,000 per class with an early enrollment child. The fines could total $3.1 million.

A penalty on kids that districts aren’t paid for: ‘double penalty’

Districts are also reeling from what they say will be a double penalty: The state pays them nothing for early enrollment kids, yet will fine them for not meeting the stricter guidelines.

School districts receive average daily attendance (ADA) funding for TK-12 students through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The state determined at what point the 4-year-olds would generate the funds based on its timeline of students eligible to enroll.

Three categories of TK students — age-eligible, early admittance and the new early enrollment — exist. Age-eligible students in 2023-24 had birthdays prior to April 2, falling within the state’s timeline, and generated funds from the first day of school.

Those enrolled ahead of the timeline with birthdays until June 2, considered early admittance kids, generated funding when they turned 5.

The newest category of students — early enrollment kids with birthdays after June 2 — did not generate funding at all. Before the change, districts enrolling students with June 3-30 birthdays could generate state funding once they turned 5.

“We’re going to take a penalty for students that we’re not getting revenue for in the first place,” Garcia said about districts educating students without the funding. “It’s unjust.”

But what can be done now?

The summer 2023 legislative changes for the 2023-24 school year didn’t leave enough time for many districts to comply with the stricter requirements.

Still, some refused to turn away families, knowing they’d incur penalties. And unless further legislative action is taken this summer, those districts could be penalized millions of dollars for not meeting the tougher requirements.

Existing legislation does not allow districts that are caught out of compliance to avoid penalties; however, the penalty can be waived through the legislative process, relief that Garden Grove and Downey Unified have been seeking for the 2023-24 school year.

Assembly Bill 2548, proposed by Assemblymember Tri Ta of northwestern Orange County, would waive the 2023-24 penalties on districts offering early TK.

In a letter to legislators, the Association of California School Administrators, the California Association of Suburban School Districts, Small School Districts’ Association, county education offices and school districts supported the legislation because the 2023-24 school year was weeks away from starting when the July 2023 trailer bill implemented the early enrollment regulations. In all, nearly 50 school districts, not including multiple districts represented by county education offices, supported the proposed waiver.

The Early Care and Education Consortium, according to a bill analysis completed by the Legislature, argued against the bill because it “disregards the legislative intent” in enacting the 1:10 ratio and 20-student max for classes with early enrollment students, which ensure student safety.

The bill to waive the 2023-24 penalties failed to make it out of committee.

Another option to address penalties for the 2023-24 year is through budget trailer bill language, which can make the penalties effective after a certain date or exempt districts from penalties imposed.

The existing draft of this year’s education trailer bill does not include changes for TK penalties.

Impacting students, now and in the future

Downey Unified had 70 early enrollment students spread across about 15 classes.

“We could have pulled these kids out of this classroom, moved them to other schools in our district, but we just didn’t feel that was right,” deputy superintendent Roger Brossmer said. “That was just not something we were willing to put our kids and our families through.”

The impact of maintaining enrollment: about $1 million in possible penalties.

Going Deeper

An audit of this school year can be conducted now that the school year has ended but any fiscal penalties won’t be accessed until after the state education department reviews the audit findings, something that may not occur until the spring semester of the 2024-25 school year.

The district would lose funding from the Local Control Funding Formula in the amount of its penalties —reducing services for students, Brossmer said.

Because the penalty is accessed up to a year later, Downey Unified officials questioned the intent of the penalty, which takes money away from students.

“What is the value of a penalty after the year has already commenced and been funded?” said Robert McEntire, assistant superintendent of business services. “We have served these children, so who benefits from this penalty? This doesn’t help anybody.”

Fiscal penalties for noncompliance are a common practice in education. Violations for LCFF unduplicated pupil counts, K–3 grade span adjustments, instructional time, the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program and TK can result in penalties following audit findings, according to the state education department.

The penalties ensure “effective accountability,” California Department of Education Communications Director Elizabeth Sanders said.

“Penalizing districts is never our goal,” she said. “The related penalties (for TK requirements) … are to ensure that there’s appropriate and effective support of students. The goal is never to collect a penalty; it’s to support and ensure compliance with what kids need.”

To Downey Unified leaders, the resulting penalties from the 2023 trailer bill legislation punish districts for trying to meet the needs of their families.

As a result, for the 2024-25 school year, Downey Unified will not enroll students with birthdays after June 2.

“There are another potential 70 students out there with birthdays between June 3 and June 30 that we are not going to have in our schools because we are reticent as a result of what’s happened,” Garcia said. “We don’t feel like we’re able to fully serve our community to the best we can because of the experience that we’ve gone through this year. And that’s disappointing.”

)