Carol Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education, points out that the once promising charter school industry is now in decline. Fifteen years ago, promoters of charter schools boasted of charter school miracles, of closing achievement gaps and saving poor kids who were “stuck in failing public schools.”

The charter industry lobby won federal funding for charter school expansion. Bill Gates put millions into charters and subsidized a propaganda film to sell the public on the remarkable success of privately run charter schools.

But the miracle dissolved. Some of the “best” charters were selecting their students carefully and/or dropping students who fell behind. Many charters failed. Others folded. Some closed because of low enrollment. Some closed because their owners were corrupt. it’s not a lack of money. The federal government is now pouring $500 million every year into charter growth.

The movement is in decline because the magic is gone.

Carol Burris wrote about the decline of the charter industry in The Progressive:

Thirty years ago, charter schools stood for possibility. At their inception in the 1990s, they were supposed to be nimble, innovative, community-driven alternatives to traditional public schools—labs of experimentation led by teachers and grounded in equity. But in 2025, the movement finds itself at a turning point, not because it succeeded, but because it strayed too far from its original vision.

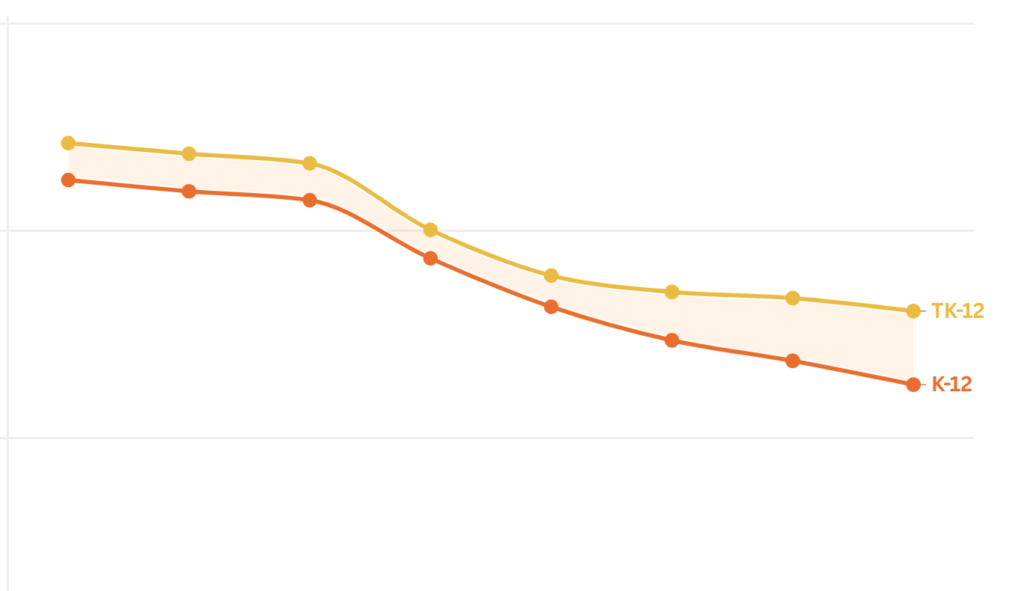

The first installment of a new report, titled “Charter School Reckoning: Decline, Disillusionment, and Cost,” by the National Center for Charter School Accountability (NCCSA) lays bare a system in decline. Closures are accelerating. Enrollment is stagnating. And beneath the rhetoric of “choice” and “opportunity,” a harsh reality has emerged: a sector in retreat, propped up by unchecked federal funding and powerful lobbying interests.

In the first six months of 2025 alone, fifty charter schools announced their closures. Some disappeared with less than a week’s warning. These schools join more than 160 others that vanished during the previous year. Between school years 2022-23 and 2023-24, the number of charter schools in the United States increased by only eleven. Last September, North Carolina’s Apprentice Academy closed days after opening for the school year. Ohio’s Victory Charter gave families two weeks’ notice. In Minnesota and Texas, charter schools folded before winter break. And last month, just weeks before the new school year was set to begin, yet another charter school in Colorado closed its doors.

And yet, federal investment in the charter school industry hasn’t skipped a beat. The U.S. Department of Education’s Charter Schools Program (CSP), created in 1994 to provide seed money to start charter schools, began with a modest $4.5 million. It now burns through half a billion taxpayer dollars a year. Much of that money is awarded by private contractors who are paid to review applications who provide minimal vetting. Their decisions are based solely on what’s written in grant applications—inviting exaggerated claims and even fiction. One 2022 federal audit found that nearly half the schools promised by Charter Management Organization grant recipients never materialized.

Even more troubling, many of the charter schools that have opened with the help of CSP funding have collapsed. The NCCSA report notes that of the fifty closures so far in 2025, nearly half had received a combined $102 million in federal start-up and expansion grants, according to a search of U.S. Department of Education and state databases.

So why does the funding from the federal government continue to flow? One reason is a myth that refuses to die: the million-student waitlist to get into charter schools. This talking point, originally peddled in 2013 by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, resurfaced in June 2025 by U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon during a Senate hearing. But the figurewas debunked more than a decade ago.

The stark truth is that demand for charter schools is often overestimated. Low enrollment is the number one reason charters shut down. A 2024 study by NCCSA and the Network for Public Education found that nearly half of all charter school closures between 2022 and 2024 were due to insufficient enrollment. Of the fifty closures in the first half of 2025, twenty-seven cited low enrollment as the primary cause.

Consider Florida’s Village of Excellence Academy, which closed with just one day’s notice in January 2025. Its enrollment had fallen from 230 in 2020 to just seventy-eight students. The school is not an anomaly. In 2023-24, 12 percent of all charter schools enrolled fewer than 100 students.

Meanwhile, at the other extreme, mega-charters such as Commonwealth Charter Academy (CCA) in Pennsylvania have student populations that are ballooning beyond reason. CCA, a virtual charter school with students across Pennsylvania, now enrolls more than 23,000 students—making it the largest K-12 school in the country. It spent nearly $9 million on advertising in the 2022-23 school year alone and $196 million on real estate since 2020—for a cyber school that delivers its instruction without the need for brick-and-mortar buildings. But student outcomes are dismal: just 11 percent proficiency in English, 4.7 percent proficiency in math, and a graduation rate far below the state average.

Then there’s Highlands Community Charter in California, a school that billed itself as a second chance for adults but instead became a case study in fraud. According to a state audit, Highlands took more than $180 million in funding to which it was not eligible and spent the money inappropriately. The school paid $80,000 for staff to attend a conference at a luxury hotel in Hawaii. Teachers were also employed without proper credentials, often because there was only one teacher for every fifty-one students. Graduation rates were between 2 and 3 percent. Following the audit, the entire board has resigned in disgrace and the state has requested a $180 million reimbursement.

This is not innovation. It’s exploitation of taxpayers and at-risk students.

And yet, federal dollars continue to pour into this shrinking, scandal-prone industry. Policymakers invoke waitlists that don’t exist. Authorizers, who are supposed to oversee charter schools, look the other way, incentivized by per-pupil funding kickbacks. Taxpayers are footing the bill for schools that fail to open, fail to serve, or fail to survive.

The question is no longer what charter schools were once meant to be. It’s whether the sector can be reformed at all. As Congress considers the next education budget, we urge lawmakers to ask: Why are we funding growth that isn’t happening? Why are we subsidizing failure? It’s time to stop chasing the ghost of what charter schools might have been—and start holding the system accountable for what it has become.

)

)