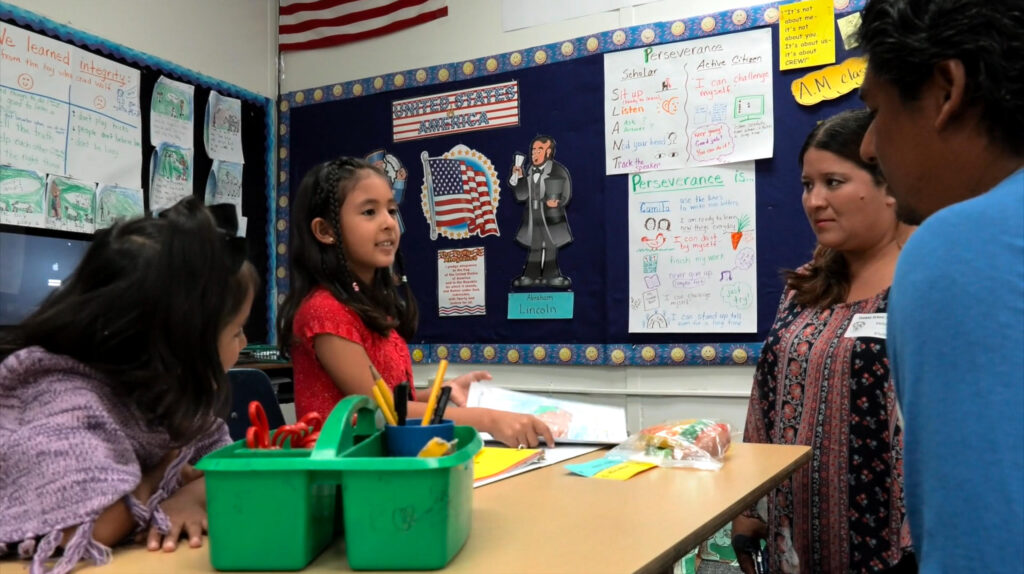

Credit: Katie Schneider Gumiran and Rosa Gaia for Conway Elementary

An instructional leader in a Bay Area school district told me last week that while they are a bright spot in improving reading for the last three years, they still haven’t recovered to pre-pandemic levels. “Our biggest pain point is writing. Our gaps start in ELA, but we see them in science and social studies too.”

This district isn’t alone; schools throughout California are struggling to improve writing across the curriculum. What might we do differently?

In their new book, Learning Together, Elham Kazemi and colleagues suggest school leaders work with teachers to analyze student writing more regularly. Reviewing a set of informational essays, or an extended project in biology, could be the center of more grade-level planning meetings or districtwide professional learning days.

The pioneer in this approach has been Ron Berger, one of the co-founders of EL Education, a national non-profit that partners with K-12 educators to transform their schools. Berger has been a mainstay of High Tech High’s Deeper Learning conferences in San Diego and has taught more than 300 workshops around the country, all of them closely examining examples of student work.

In Leaders of Their Own Learning, the instructional guide he co-authored, Berger tells the story of coaching a high school physics teacher who says, “The students’ lab reports are terribly written and it’s driving me crazy.”

Ron asks if she’s ever shown her students a model of a good lab report and she replies that she has not.

When given the chance to closely study an exemplary lab report, her students are surprised at the vocabulary and level of precision in it. A number laughed at how low their own standards had been.

“For all the correcting we do, directions we give, and rubrics we create about what good work looks like,” writes Berger, “students are often unclear about what they are aiming for until they actually see and analyze strong models.”

Ron Berger used to lug around a giant black bag of student essays, labs, and video presentations to discuss at workshops. Eventually, with support from the Hewlett Foundation, and collaborating with Steve Seidel at Harvard University, Berger built an online museum for displaying student work.

Models of Excellence showcases 500 examples of great student writing and other projects from around the U.S. and the world. California students have contributed sixty pieces, including a Kids Guide to California National Parks created by 2nd graders from Big Pine, and an analysis by 6th graders on the water quality of Lake Merritt in Oakland.

Here are three ways districts and schools across California can improve writing by studying their own student work:

First, form a study group. In grade-level meetings or working across the district, teachers and a coach can assemble their own models of excellent student writing. The group can link the models to criteria which guide students’ efforts; the more concrete, the better. The study group can use the rubrics and student checklists developed by the Vermont Writing Collaborative for all genres of writing at all grade levels.

After teaching a lesson where third graders critiqued a fantasy story, Berger reflects, “It’s much more powerful to bring in models of great work. Then have the kids be detectives and have the excitement of discovering and naming the qualities of great writing — humor, powerful words, well-drawn character — in their own words.”

Second, get the feedback right. Dylan William writes in Embedded Formative Assessment that most feedback in schools is accurate, but falls short of showing the learner how to move forward. He tells of a science student who reads he needs to be more systematic. “If I knew how,” the student tells his teacher, “I would have done it the first time.”

Students can resist revising their work, so Berger suggests teachers and peers follow this mantra about feedback: “Be Kind, Be Specific, Be Helpful.” Keeping this in mind, writing three or four drafts of an essay becomes a part of the school culture.

Finally, make the writing visible. Tina Meglich, principal of Conway Elementary in Escondido, transformed her school by displaying curated student work throughout the library and hallways. “Kids will ask, ‘Who wrote that essay on Esperanza Rising?’ They’re fascinated by each other’s work, and they inspire one another to do better because of it.”

Analyzing student writing in this way not only raises the quality of the work, but it also instills in students a vision of what’s possible. “I believe that work of excellence is transformational,” Berger writes. “After students have had a taste of excellence, they’re never satisfied with less; they’re always hungry.”

•••

David Scarlett Wakelyn is a consultant at Upswing Labs, a nonprofit that works with school districts and charter schools to improve instruction. He previously was on the team at the National Governors Association that developed Common Core State Standards.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.