Polk County Public Schools expressed relief July 25 after learning that the Trump Administration would release about $20 million in funding that it had withheld for weeks.

The district issued a news release, noting that the previously frozen grants in four categories directly fund staff positions and services supporting migrant students, English-language learners, teacher recruitment and professional development, academic enrichment programs and adult education.

The relief, though, was only partial. When the district eight days earlier took the unusual action of issuing a public statement warning of “significant financial shortfalls,” it cited not only the suspended federal grants but also state policies.

Legislative allocations for vouchers — scholarships to attend private schools or support home schooling — combined with increased funding for charter schools “are diverting another $45.7 million away from Polk County’s traditional public schools,” the district’s news release said.

The statement reflected warnings made for years by advocates for public education that vouchers are eroding the financial stability of school districts.

“The state seemingly underestimated the fiscal impact that vouchers would have,” Polk County Schools Superintendent Fred Heid said in the July 17 news release. “As a result, the budget shortfall has now been passed on to school districts resulting in a loss of $2.5 million for Polk County alone. We now face having to subsidize state priorities using local resources.”

Florida began offering vouchers in the 1990s, initially limiting them to students with disabilities and those in schools deemed as failing. Under former Gov. Jeb Bush, the state expanded the program in 2001 to include students from low-income families.

The number of students receiving vouchers rose as state leaders adjusted the eligibility formula. In 2023, the Legislature adopted a measure introducing universal vouchers, available to students regardless of their financial status.

Get the Daily Briefing newsletter in your inbox.

Start your day with the morning’s top news

Delivery: DailyYour Email

All of Polk County’s legislators voted for the measure: Sen. Ben Albritton, R-Wauchula; Sen. Colleen Burton, R-Lakeland; Rep. Melony Bell, R-Fort Meade; Rep. Jennifer Canady, R-Lakeland; Rep. Sam Killebrew, R-Winter Haven; and Rep. Josie Tomkow, R-Polk City.

Allotment for vouchers swells

The vouchers to attend private schools are known as Florida Empowerment Scholarships. The state also provides money to families through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and the Personalized Education Program, which financially supports home-schooled students.

The money for vouchers comes directly from Florida’s public school funding formula, the Florida Education Finance Program.

Families of students receiving such scholarships have reportedly used the money to purchase large-screen TVs and tickets to theme parks, spending allowed by Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that administers most scholarships.

The state allotment for vouchers has swelled from $1.6 billion in the 2021-2022 school year to about $4 billion in fiscal year 2024-2025, according to an analysis from the Florida Policy Institute, a nonprofit with a progressive bent.

0:19

/

0:19

In Polk County, 5,023 students claimed vouchers in the 2021-2022 school year, according to the FPI report. Those scholarships amounted to just over $41 million.

The figures rose in 2022-2023 to 6,124 students and nearly $58 million. The following year, the total was 7,854 students and nearly $72 million.

In the 2024-2025 school year, 11,297 students in Polk County received vouchers totaling more than $97 million, FPI reported.

A calculation from the Florida Education Finance Program projects that nearly $143 million of Polk County’s state allotment for education will go to Family Empowerment Scholarships in the 2025-2026 school year, a potential increase of about 47%. The total reflects 16.3% of Polk County’s state funding.

Statewide, the cost of vouchers has risen steadily and is projected to reach nearly $4 billion in the 2025-26 school year.

Florida’s State Education Estimating Conference report from April predicts that public school enrollment will decline by 66,000 students over the next five years, or about 2.5%. Over the same period, voucher use is projected to increase by 240,000.

The state projected that only about 27% of the new Family Empowerment Scholarship recipients would be former public school students.

Subsidizing wealthy families?

Since the state removed financial eligibility rules for the scholarships in 2023, voucher use has soared by 67%, the Orlando Sentinel reported in February. And the majority of scholarships have been claimed by students who were already attending private schools.

By the 2024-25 school year, more than 70% of private school students were receiving state scholarships, the Sentinel reported. The total had been less than a third a decade earlier.

The Sentinel published a list of private schools, with the number of students on state scholarships from the years before and after the law took effect.

Among Polk County schools, Lakeland Christian School saw a jump from 40 to 89, a rise of 122.5%. The increases were 102.7% for All Saints Academy in Winter Haven and 60.3% for St. Paul Lutheran School in Lakeland.

The scholarships available to Polk County students for the 2025-2026 school year are $8,209 for students in kindergarten through third grade; $7,629 for those in grades four through eight; and $7,478 for students in ninth through 12th grades. Those figures come from Step Up for Students.

There have been news reports of private schools boosting their tuition rates in response to the universal voucher program. Lakeland Christian School’s advertised tuition for high school students has risen from $14,175 in 2022-2023 to $17,975 for the current school year, a jump of 26.8%.

Polk school district prepares to enforce state law banning most student cell phone use

Stephanie Yocum, president of the Polk Education Association, decried the trend of more state educational funding going to private schools.

“In the 2023-24 school year, 70% of Florida’s universal vouchers went to students who already were in private schools,” Yocum said. “Seventy percent of those billions and billions and billions of dollars are going to subsidize already wealthy families, and our state continues to push welfare for the wealthy, while they are siphoning off precious dollars from our students that actually attend a public school, which is still the supermajority of children in this state.”

Critics of vouchers point to Arizona, which instituted universal school vouchers in 2022. That program cost the state $738 million in fiscal year 2024, far more than Arizona had budgeted, according to a report from EdTrust, a left-leaning advocacy group.

Arizona is facing a combined $1.4 billion deficit over fiscal years 2024 and 2025, EdTrust reported. The net cost of the voucher program equals half of the 2024 deficit and two-thirds of the projected 2025 deficit, it said.

Meanwhile, there is a move toward a federal school voucher program. The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” that Congress adopted in early July uses the federal tax code to offer vouchers that students could use for private school tuition or other qualifying education expenses.

The Senate revised the initial House plan, making it not automatic but an opt-in program for each state. The Ledger emailed the Florida Department of Education on Aug. 4 asking whether the state plans to participate. A response had not come by Aug. 6.

The federal program could cost as much as $56 billion, EdTrust reported. Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, called the program “a moral disgrace,” as NPR reported.

Canady: Let parents choose

Proponents of vouchers say that it is essential to let students and parents choose the form of education they want, either through traditional public schools, charter schools, private schools or homeschooling.

Canady, who is in line to become state House Speaker in 2028, defended the increase in scholarship funding.

“In Florida, we fund students — not systems,” Canady said by text message. “Parents have the freedom they deserve to make the decisions that are best for their own children. There are a lot of great school options — public district, public charter, private, and homeschool.”

She added: “In Florida, decisions about which school a child will attend are not made by the government — parents are in control.”

Canady has taught at Lakeland Christian for nearly 20 years and is director of the school’s RISE Institute, which encompasses research, innovation, STEM learning and entrepreneurship. She began her career teaching at a public school.

None of Polk County’s other legislators responded to requests for comment. They are Rep. Jon Albert, R-Frostproof; Rep. Jennifer Kincart Jonsson, R-Lakeland; and Albritton, Burton and Tomkow.

Canady noted that 475 fewer students were counted in Polk County Public Schools for funding purposes in the 2024-2025 than in the previous year.

“That reflects the choices that families have made,” Canady wrote. “During the same time, the Florida Legislature increased teacher pay by more than $100 million dollars and continues to spend more taxpayer money on education than ever before.”

She added: “Education today looks different than it did decades ago, and districts around the state are all adapting to the new choice model. Funding decisions should always be about what is good for students and honor the choices that families make.”

The 475 net loss of students in Polk’s public schools last year is far below the increase of 3,443 in Polk students receiving state scholarships.

Questions of accountability

Yocum said that public school districts face certain recurring costs that continue to rise, no matter the fluctuations in enrollment resulting from the use of vouchers.

“You’ll still have the same — I call them static costs, even though those are going up — for maintenance, for buildings, for air conditioning, for transportation,” Yocum said. “All of those costs still exist. But when you start to siphon off dollars that public schools should be getting to run a large-scale operation of educating children, then we are doing more and more with less and less.”

Yocum also raised the question of accountability. The Florida Department of Education carefully controls public schools, largely dictating the curricula they teach, overseeing the certification of teachers and measuring schools against a litany of requirements codified in state law.

Public schools must accept all students, including those with disabilities that make educating them more difficult and costly.

By contrast, Yocum said, private schools can choose which students to accept or reject. The schools are free from much of the scrutiny that public schools face from the Department of Education.

The alert that Polk County Public Schools issued on July 17 mentioned another factor in its financial challenges.

“PCPS is facing an immediate $2.5 million state funding shortfall due to what state officials have described as dual-enrollment errors that misallocated funding for nearly 25,000 Florida students,” the statement said.

That seemed to refer to a “cross check” that the Florida Department of Education performs twice a year, said Scott Kent of Step Up for Students. The agency compares a list of students on scholarships with those reported as attending public schools.

If a student appears on both lists, the DOE freezes the funding. Step Up for Students then contacts the students’ families and asks for documentation that they were not enrolled in a district school, Kent said.

“This is a manual process that can be time-consuming, as the state and scholarship funding organizations want to ensure accuracy and maintain the integrity of the scholarship programs,” Kent said by email. “The DOE currently is checking the lists before releasing funds to Step Up to pay eligible students.”

In the 2025 legislative session, the Florida Senate passed a bill that would have clarified which funds are dedicated to Family Empowerment Scholarships, a way of addressing problems in tracking students as they move between public and private schools. But the bill died, as the state House failed to advance it.

Yocum said the House rejected transparency.

“They want it to look like they’re funding public schools at the level that they should be funding it, where, in reality, more and more of our dollars are running through our budgets but being diverted to corporate charter, private schools and home schools that have no accountability to our tax dollars,” she said.

Effect of charter schools

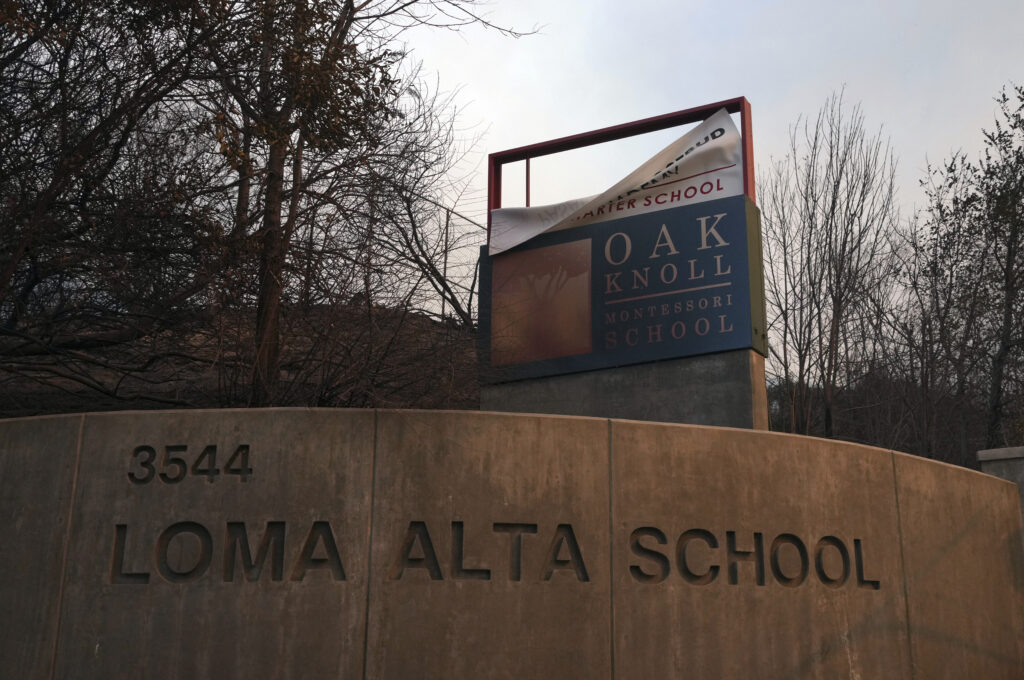

The warning from the Polk County school district mentioned funding for charter schools as part of a “diversion” of $45.7 million traditional public schools.

Charter schools are publicly funded schools that operate independently. Polk County has 36 charter schools covering all grades. Those include two charter systems: Lake Wales Charter Schools with seven schools, and the Schools of McKeel Academy with three.

Some other charter schools are affiliated with national organizations, including for-profit companies.

Yocum lamented the passing of public funds through the school district to charter schools, though specified that she had no criticism of the McKeel or Lake Wales systems.

“We’re talking about the corporate-run charters that are in it to make money,” she said. “We keep seeing billions and billions of our state dollars diverted to those money-making entities that do not make decisions in the best interest of children. They make decisions in the best interest of their bottom line.”

Canady sponsored a bill in 2023 establishing the transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars from traditional public schools to charter schools’ capital budgets by 2028. It passed with the support of all Polk County lawmakers, and Gov. Ron DeSantis signed it into law.

The Florida Legislature passed a bill in the 2025 session (HB 1105), co-sponsored by Kincart Jonsson, that requires public school districts to share local surtax revenues with charter schools, based on enrollment share.

The bill, which DeSantis signed into law, also makes it easier to convert a public school into a charter school, allowing parents to initiate the change without requiring cooperation from teachers. It also authorizes cities or counties to transform public schools with consecutive D or F grades into “job engine” charter schools.

Gary White can be reached at gary.white@theledger.com or 863-802-7518. Follow on X @garywhite13.