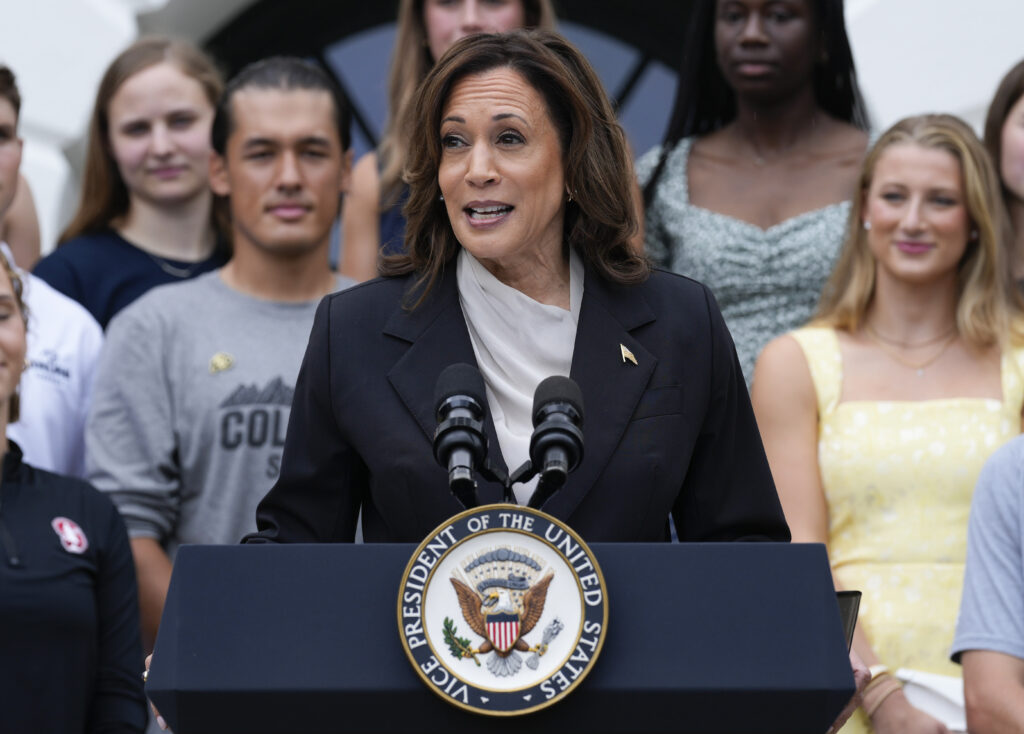

Participants in a Climb Together networking event that provides an opportunity for students to build connections and make contacts.

Credit: Courtesy of Climb Together

A recent study found a whopping 85% of jobs are filled through relationships. Imagine a network of successful professionals eager to hear about your career goals and guide you through the professional maze. As new grads begin looking for jobs, it’s important they understand the power of social capital — the connections you make that become your golden ticket past the crowded applicant pool.

Unfortunately, access to networks isn’t evenly distributed. Elite universities often help students cultivate social capital simply by having students engage in so many activities — a cappella clubs, dance, secret societies, dorm life, parties, group projects; these are all ways peers build meaningful relationships that open doors for life.

Those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are at a severe disadvantage because these kinds of activities are not always available or accessible. Time is our most precious commodity, and students who need to work to make ends meet have far fewer opportunities to build relationships.

Here’s the encouraging news: Research shows that “weak ties,” or casual acquaintances, can be just as valuable as close friends in securing job referrals. This means students don’t need years of deep connections — they can build a powerful network by honing their relationship-building skills.

Community colleges, vocational programs and even high schools can become social capital incubators, leading the way to unlocking social capital by teaching their students to build professional relationships and then broker access to alumni from their institutions. Imagine students learning the art of conversation: asking insightful questions, actively listening and crafting compelling requests. They can then practice these skills by connecting with industry professionals and/or alumni. This targeted approach, less time-intensive than building deep friendships, equips students to navigate the professional landscape with confidence.

Educational institutions can help students build social capital and improve their job prospects through several strategies:

- Assemble a dedicated team: Engage stakeholders across leadership, faculty, staff and career services to develop and implement a social capital building strategy. This team can reach out to alumni and associated professionals, inviting them to participate in a program that helps graduating students with their job search. As the program grows, it can expand to multiple educational and professional tracks.

- Offer targeted classes: Institutions should provide courses that teach students how to build and leverage social capital effectively. The curriculum can cover topics such as developing personal narratives, self-advocacy, discovering connections, LinkedIn engagement, crafting effective emails, follow-up techniques, and the art of conversation. Hands-on practice is crucial for students to gain confidence in engaging professionals and making asks for introductions or referrals.

- Facilitate connections: After assessing learner readiness, institutions can match job seekers with alumni and other connectors. This facilitates the formation of new relationships and broadens job referral opportunities. Recognizing that relationship-building and job-searching are skills that need to be learned, institutions should provide guidance and support throughout the process.

By helping students broker access to professionals, higher education will also be able to address a growing concern: student disillusionment about attending college. Students invest in education expecting career opportunities, but recent graduates (especially those of color or from low-income backgrounds) face higher unemployment rates than before the pandemic. New grads have consistently fared worse than other job seekers since January 2021, and that gap has only widened. The latest unemployment rate for recent graduates, at 4.4%, is higher than the overall joblessness rate and nearly double the rate for all workers with a college degree.

These numbers are even lower for students of color and students from low income backgrounds. This disconnect highlights a need to bridge the gap between academic preparation and real-world employment.

This paradigm shift in how institutions prepare students for the workforce creates a win-win: Students gain valuable connections, alumni stay engaged with their alma mater, and institutions see higher graduation rates and lower loan defaults.

Our education system needs a refresh. It’s time to recognize that preparing students for the future workforce goes beyond just technical skills. By prioritizing social capital development, schools and workforce programs can level the playing field, creating a more diverse and skilled talent pool for businesses.

Let’s empower all students to navigate their career paths, not get lost in the application maze. They hold the key — the social capital key — to unlocking their full potential.

•••

Nitzan Pelman is the CEO of Climb Together, a nonprofit working with schools and workforce programs to teach students the art of building social capital and developing relationships and the founder of Climb Hire, a national nonprofit that blends relationships and social capital with in-demand skills to help overlooked working adults break into new careers.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.