Zaidee Stavely/EdSource

Top Takeaways

- The 0.54% decline was steeper than last year but not as dramatic as the plunge at the peak of the pandemic.

- The drop in enrollment was somewhat offset by the expansion of transitional kindergarten.

- The number of students identified as homeless jumped 9.3% from last year.

New state data released Wednesday shows that California’s TK-12 enrollment has continued its steady post-pandemic decline. At the same time, the number of poor and homeless students has been increasing.

For the 2024-25 school year, enrollment statewide declined by 31,469 students or 0.54%, compared to last year. California now has 5.8 million students in grades TK-12 compared to 6.2 million students in 2004-05. The new data from the state is based on enrollment counts for the first Wednesday in October, known as Census Day.

This year’s decline is a little steeper than last year’s, which was 0.25%, but relatively flat compared to the enrollment plunge at the peak of the pandemic.

“The overall slowing enrollment decline is encouraging and reflects the hard work of our LEAs across the state,” said state schools Superintendent Tony Thurmond in a statement.

The drop in enrollment was somewhat offset by the state’s gradual rollout of transitional kindergarten. More students were eligible for the new grade than last year, and the numbers reflect that. An additional 26,079 students enrolled in transitional kindergarten — a 17.2% increase — while most other grade levels saw dips in enrollment.

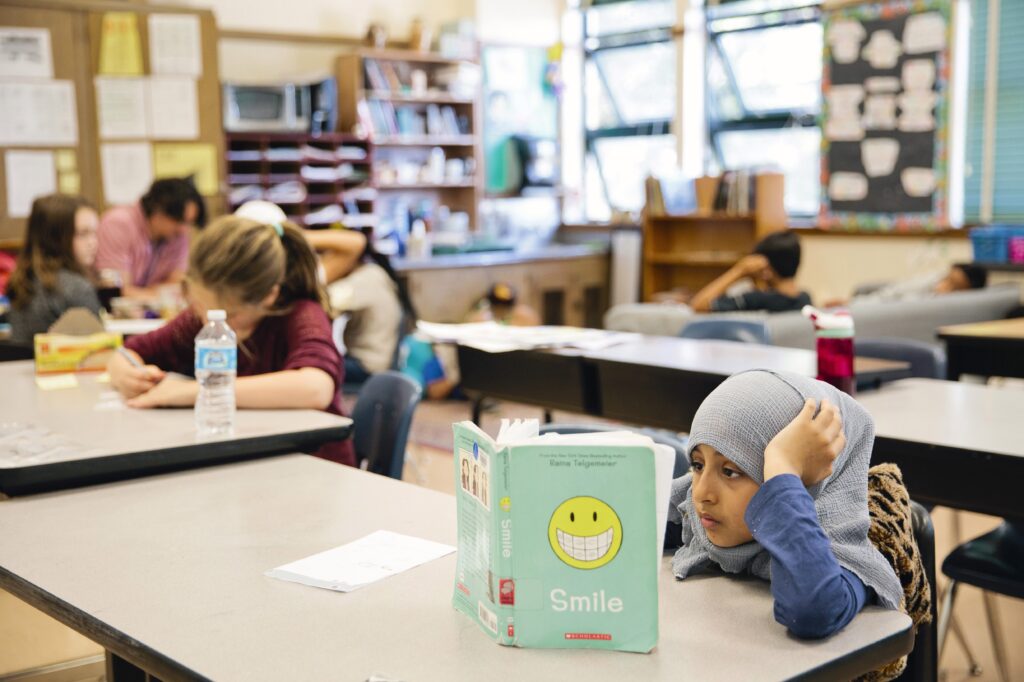

The new state data also reflect an increasing number of students who are experiencing economic hardship. An additional 32,179 students now qualify as socioeconomically disadvantaged, a 0.9% increase. This data show that 230,443 students were identified as homeless — a 9.3% increase from the last school year.

The number of students identified as English learners decreased by 6.1%. This is largely in response to Assembly Bill 2268, which exempted transitional kindergarten students from taking the English Language Proficiency Assessment for California (ELPAC).

Previously, schools tested transitional kindergarten students with a screener meant for kindergarten students, which was not appropriate for younger students and was therefore unreliable, according to Carolyne Crolotte, director of policy at Early Edge California, a nonprofit organization that advocates for early education. The state is in the process of creating a new screener, but in the interim, almost no English learners are being identified in this grade.

State officials attribute much of the enrollment decline to demographic factors, such as a declining birth rate.

Enrollment saw its greatest decline in regions of the state with higher housing prices, notably Los Angeles County and Orange County. There is growth in more affordable areas of the state, such as the San Joaquin Valley and Northern California, including the Sacramento area.

Enrollment in charter schools has steadily increased at the same time enrollment in traditional public school is decreasing. This year an additional 50,000 students attended a charter. Now 12.5% of students in California are enrolled in charter schools, which is up from 8.7% ten years ago.

The California Department of Education characterized transitional kindergarten numbers, which went up 17.2%, as a “boom.” A release from the department stated that 85% of school districts are offering transitional kindergarten at all school sites. It also said that transitional kindergarten is creating more spaces in the state preschool for 3-year-olds.

However, the enrollment numbers for transitional kindergarten are well below early estimates advanced by the Learning Policy Institute in 2022 which had estimated that 60% to 75% of eligible students would enroll in transitional kindergarten. The just released numbers show closer to about 40% of eligible students are opting in for transitional kindergarten, which according to Bruce Fuller, professor of education and public policy at UC Berkeley, is “not exactly universal preschool.”

The Governor’s recently released budget revision noted that lower daily attendance prompted him to reduce funds aimed at transitional kindergarten by $300 million. The state plans to lower the student to adult ratio in these classrooms from 12:1 to 10:1 next year, but will need less money to do so because of lower enrollment.

Transitional kindergarten has been gradually expanding over a five-year period to include all 4-year-olds. This school year, all students who turn five years old between Sept. 2 and Jun. 2 were eligible. The expansion to all 4-year-olds will be complete in the 2025-26 school year.

The expansion of transitional kindergarten doesn’t seem to be reaching more eligible four-year-olds than the previous system of private preschools, state preschools and Head Start, Fuller said. He notes that enrollment in those programs has been in decline at the same time that transitional kindergarten has been growing.

Crolotte praised the state for its expansion of transitional kindergarten but said that some families may not know that their children are eligible for the program.

“I think more work needs to be done about communication to families and knowing that this is available to them,” Crolotte said.