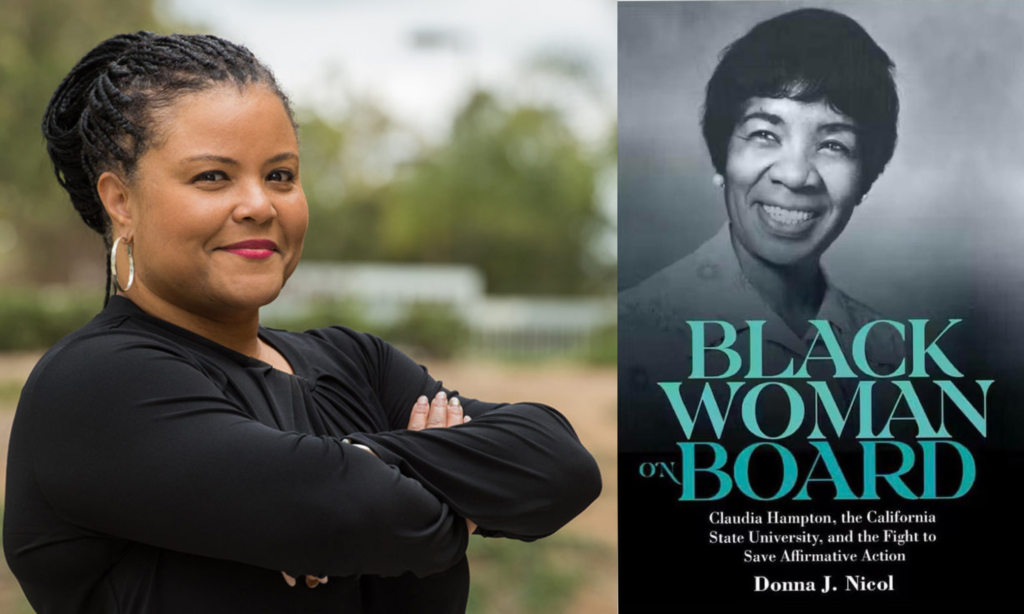

Donna J. Nicol, author of a book about Claudia Hampton, the first Black woman to serve on the Cal State board of trustees.

Credit: Courtesy of Donna J. Nicol

It was the photo of a Black woman dressed in university regalia that caught Donna J. Nicol’s eye.

“Trustee Claudia Hampton,” the caption read, “appointed by Reagan.”

Nicol, an associate dean at Cal State Long Beach who studies the history of racism and sexism in higher education, was stunned. Ronald Reagan, as governor, opposed mandatory busing as a tool of school desegregation and, as president, attempted to undo affirmative action policies in the workplace. How could it be, Nicol wondered, that he appointed the first Black woman to sit on the California State University board of trustees? And what did Hampton do once she got there?

“Black Woman on Board: Claudia Hampton, the California State University, and the Fight to Save Affirmative Action”, Nicol’s recent book, answers those questions and others about Hampton’s two-decade stint on the board of trustees that governs the 23-campus public university system. Prior to her appointment at CSU, Hampton worked to enforce desegregation orders in the Los Angeles Unified School District and earned a doctoral degree from the University of Southern California. She rose to the CSU board when an opportunity to meet then-Gov. Reagan’s education secretary turned into an informal vetting process for a board seat. (She met Reagan only once, as far as Nicol can tell, an encounter Hampton described as pleasant.)

The book tracks Hampton’s emergence as a master tactician and a skillful diplomat on the Cal State board of trustees. Initially excluded from the informal telephone calls and meetings in which fellow board members discussed CSU business outside of regular meeting times, Nicol writes, Hampton traded votes with trustees to earn influence. Eventually, she began hosting board members for dinner to ensure she had a voice in important decisions, a practice she continued as board chair. Hampton also withstood subtle (and not so subtle) racism to win support for policies benefiting low-income students of color.

Though at first skeptical of Hampton’s approach to board politics, Nicol came to understand her as a pragmatist who worked within the period’s racial and gender norms to wield power on a board dominated by white, wealthy and conservative men.

“I realized how genius she was,” Nicol said. “When she became board chair, she had a strategy of letting her supporters talk first, and then her opponents had to play defense later. Everything was strategic.”

Nicol also details Hampton’s work to implement, monitor and ensure funding for affirmative action programs. Soon after Hampton’s death, California voters passed Proposition 209, a 1996 ballot measure that bans state entities from using race, ethnicity or sex as criteria in such areas as public education and employment.

But Hampton’s legacy is still felt in CSU and beyond, Nicol writes. CSU created the State University Grant program after Hampton argued that increases to student fees should be offset by more need-based aid. A student scholarship named in her honor is aimed at underserved Los Angeles-area students. The California Academy of Mathematics and Sciences, a prestigious public high school that was her brainchild, continues to operate on the campus of Cal State Dominguez Hills.

Nicol counts herself among the many students to have benefited from Claudia Hampton’s advocacy. She attended an enrichment program for African American high school students at Cal State Dominguez Hills and received a State University Grant to pursue her master’s degree at Cal State Long Beach. Today, Nicol is the associate dean of personnel and curriculum at Long Beach’s College of Liberal Arts. She spoke to EdSource about the book and Hampton’s legacy.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You write about a couple of incidents in which Hampton used some savvy diplomatic skills while on the Cal State board of trustees. Would you mind walking us through an example or two of those strategies?

She was silent (at board meetings) for her first year. She didn’t talk, because she used that time to assess who were the power players, who were the people who had the capital. And so when she identified them, she said, “I have to trade votes with them.”

One of her first appointments was to be on the Organization and Rules Committee. People treated it as a throwaway committee, but she was the chair, and so she decided, “I’m going to learn all of the board policies inside and out.”

Before she passed away in (1994), she asked for a very specific rule, which is to hold presidents accountable for the implementation of affirmative action. What she wanted to ensure was that someone besides the middle manager, who would be the affirmative action officer, would be held accountable to make sure that they didn’t fall short on their affirmative action goals.

Claudia Hampton faced both subtle and overt racism that challenged the legitimacy of her role on the board. What are some examples of the discrimination that she experienced and how she was able to overcome that opposition?

She was kind of presumed incompetent, because she was a Black woman coming into the board — even though she actually had a doctorate degree coming in.

You had a trustee by the name of Wendell Witter. This is a few years in. They’re discussing affirmative action. And he yells out, “Oh my God, there’s a n— in the woodpile.” So she is taken aback by all of this, and all the men on the board, she says, are upset, too. And Wendell Witter is looking around like, “Well, what did I do? It’s just an expression.”

Hampton had a lot of experience in administration in (Los Angeles Unified), and she worked explicitly on race relations within the K-12 setting. When she got to the board, instead of yelling at Witter for what he had said, she told the board chair at the time, “I’ll talk to him individually. You keep going with that meeting.” And so the men on the board started to rally around her, because they viewed her as a political moderate, because she had every right at that moment to tell him off for the statements.

Help me to understand the victories that Hampton ultimately won with regard to affirmative action and related policies.

California Gov. Jerry Brown was actually kind of an opponent of affirmative action. He would say he supported it, but then when it came to funding, he would support (Educational Opportunity Programs, or EOPs, which help low-income and other underrepresented students attending a CSU campus), but he would not (fund) student affirmative action (in admissions) or faculty and staff affirmative action (in hiring). Hampton put a lot of pressure on Jerry Brown. She would call him out in meetings and say, “What about your commitment to these principles?’” (Hampton ultimately used her board position to ensure funding for student affirmative action pilot programs during a period of budget cuts in the late 1970s.)

There was an update in the admission standards for students (in the 1980s). And she told people, ‘Yes, we’re going to increase the admission standards, but what we’re going to do is make sure that there’s enough EOP money that would prepare students in low-income areas in order to make sure they could meet those standards.’ She was particularly focused on the fact that L.A. Unified and San Francisco Unified had these large numbers of students of color and low-income students, but they weren’t getting access to things beyond reading, writing and arithmetic. They didn’t have access to a drama club or all those sorts of things. So she made sure that the CSU put funding aside to help support (that programming).

Hampton and other affirmative action advocates’ success was short-lived because of the passage of Proposition 209, which prohibited state and local governments from considering race and other factors in public education. What were the forces that brought about Proposition 209?

You have the recession that happened in the 1990s. Wherever there’s a recession and an economic downturn, you see an uptick in either racial violence or racial animus. So that’s one big part of it. The other part is the L.A. riots of 1992 because folks are like, ‘Well, they don’t deserve affirmative action, because look at how they’re behaving in the streets.’ That’s the idea. And then you also have, in 1994, Proposition 187, which has to deal with undocumented students.

So you take all of those things – the recession, the LA riots, Proposition 187. Then, on top of that, you have (University of California regent member Ward Connerly, who championed Proposition 209) as this Black man who becomes a public face of the anti-affirmative action movement. (Connerly has said he has Native American, Black and white ancestry.) He’s kind of supercharging the debate over whether affirmative action is a good thing or not. So that’s really what led to its falling apart.

We find ourselves now in a moment when a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision has effectively ended the practice of race-conscious college admissions. Are there lessons from Hampton’s life that you feel are even more relevant today in that context?

I think that having diversity in our boards is really important because diversity leads to better policy. Too often we think of diversity as a feel-good thing — to make people feel included and inclusive. We talk about representation, but representation is more than just having two or three people from this group here; It’s really about having different perspectives so that you can write better policy.

If you look at the CSU board, it is more diverse than it was, but is it reflective of what’s happening on the ground with students? I’m at CSU Long Beach, and we have a much larger Latinx population than what is represented on the board.

I always say that the American project has been built on racism, and we don’t reconcile that. And Hampton just approaches the problem in a different way than others. I was raised in the Black radical tradition. So I had to come to terms with this pragmatic side — that we need the pragmatic and we need the radical at the same time. You need the radical to raise the consciousness of people, but you need the pragmatic in order to turn it into policy and something that has a legacy.

I also think that Hampton — her story, her life, what she did for the board— really demonstrates, in a lot of ways, people’s ignorance about how the trustees work. They’re super powerful, but they are super unnoticed. They are appointed by governors, and they are not held to account by the public.