“Double texting” and “spamming” are perhaps two of the most dreaded phrases in Gen Z lingo.

It’s intimidating to send a friend or partner multiple messages without a response, but it can be even more terrifying to come across as overbearing to a professional.

This fear, while coming from a good place of not trying to inundate recruiters, professors and professionals with messages, holds students back from advancing their careers.

It’s better to be persistent than to be absent and miss out on valuable opportunities.

If I hadn’t pushed back against my trepidation of being overbearing, I wouldn’t be writing this story for this publication.

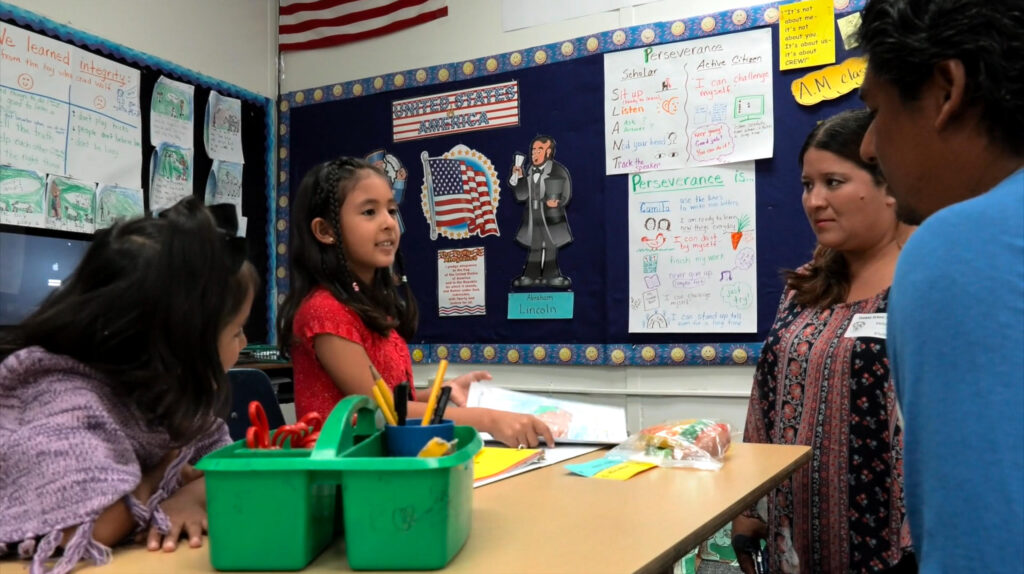

I saw a listing for EdSource’s California Student Journalism Corps in April and quickly assembled a cover letter, resume and list of bylines. Over two days, I completed everything and went back to the website — but the post was gone.

Unbeknownst to my scrambled, midterms-focused brain, the application deadline had passed and the opportunity seemingly vanished.

While I worried that a last-minute email would fall into an abyss of similar messages, my friend Brittany pushed me to send my application regardless.

I was pleasantly surprised to see a response less than 24 hours later informing me that although the cohort was mostly full, I still had a chance. After quickly submitting my documents and having a good phone interview with the internship coordinator, I was offered a position.

Now in my second semester as a Student Corps member, the experience has been invaluable. And it never would have happened if I let my intrusive thoughts win.

A quick survey through my emails reveals that I’ve sent the phrase “follow up” in some capacity to professionals or my co-workers 34 times. I should probably vary my rampant use of “follow up,” but the sentiment stands.

Not once did I receive a response saying “stop emailing me” or “you’re bothering me.” Most of my emails yielded responses thanking me for following up and apologizing for the delay.

Some of the most fulfilling experiences I’ve had as a journalist came from spur-of-the-moment messages I sent. There were plenty of unread emails, but the ones that did receive responses helped me tremendously.

I was able to attend and produce content at the 2023 Online News Association conference in Philadelphia because I applied for a scholarship opportunity I never thought I would win. At the conference, I connected with writers, editors and leaders from newsrooms I had long admired.

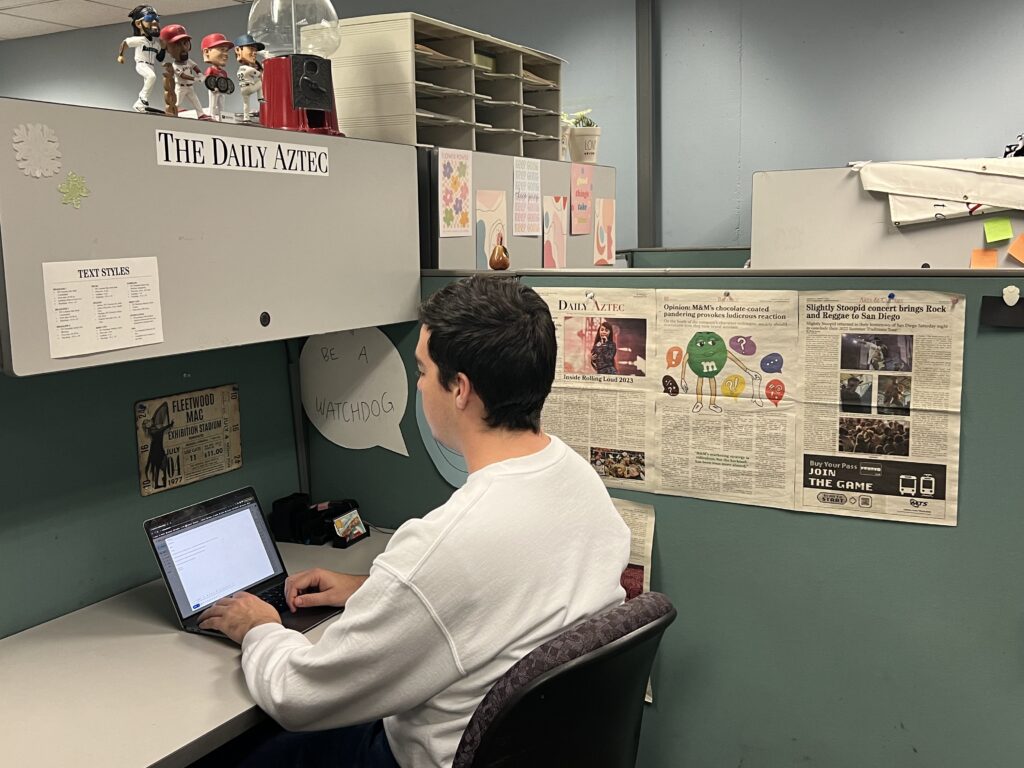

Less than a year prior, I applied to cover the hip-hop festival Rolling Loud for San Diego State University’s publication The Daily Aztec. Walking through the campgrounds filled with eager fans and thrilling performances, I couldn’t help but think what would have happened if I never sent that application.

Daniel Newell, executive director of San Diego State’s career center, works to connect students with jobs and internships during and after college. In his experience with recruiters, and previously working as one, he noted that persistence is a key quality for applicants.

“Every recruiter likes to see genuine interest and passion,” Newell said. “I’ve met so many people where they didn’t have all the requirements for the job, but man, they were persistent and they were dedicated and they were passionate. I would take a passionate person who wants to learn and get the job done any day over someone who has the experience but isn’t really gung-ho about the position.”

While these attributes are important for building connections, Newell said it’s also essential to maintain a respectable tone and demeanor when interacting with professionals.

“When you’re talking to a professional or a recruiter, you’re always going to be professional,” Newell said. “Even if you don’t think they’re sort of assessing you or judging you, they are. Every interaction is important.”

Instead of deliberating whether to send the follow-up message, students and budding professionals should focus more on how to deliver their messages. Being pushy and unprofessional can be a significant turn-off, but being persistent and professional can help you land a job.

Students aren’t alone in their endeavors to network and reach out to professionals. And you don’t have to take advice exclusively from a 22-year-old like me. The New York Times published a guide on how to get email responses by being truthful, quick and direct. The Wall Street Journal also detailed tips and tricks for sending thank-you messages after a job interview.

It’s perfectly normal to feel nervous when reaching out to people you admire or want to work with. I feel imposter syndrome all the time. But you never know what will happen when you reach out, and there’s only so much you can accomplish if you don’t ask.

•••

Noah Lyons is a fourth-year journalism major at San Diego State University and a member of EdSource’s California Student Journalism Corps.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.