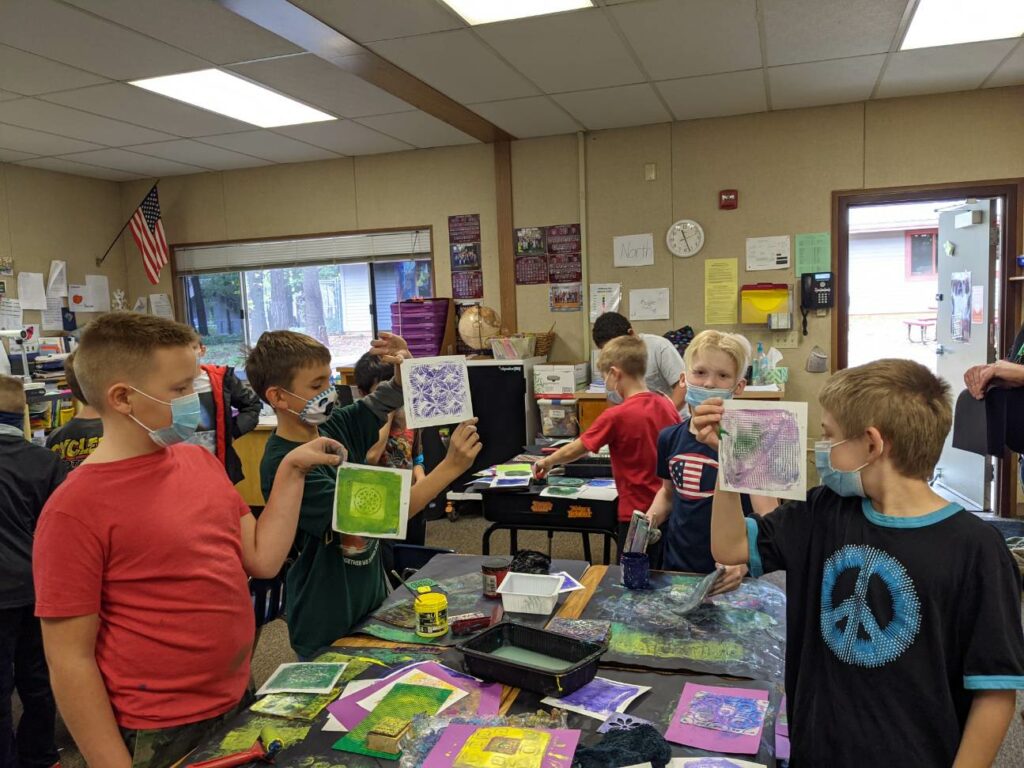

Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

At first, Caitlin Rubini, a veteran dance teacher at a school north of Sacramento, was thrilled when Proposition 28 passed with its promise of bringing arts education to all California students. Participation in the arts can help students recover from trauma, make social connections and increase engagement in school, research has long shown, all critical issues in the post-pandemic era. This kind of boost may have the greatest impact on children from low-income families, experts say, the very cohort Rubini teaches.

Her excitement turned to devastation when she heard that the dance classes she teaches at El Dorado county’s Union Mine High School are slated to be axed next year due to budget cuts, despite all the extra state funding, roughly $1 billion, now earmarked for arts education every year.

“It’s devastating. I cry most days. This is my life; I have dedicated so much energy to it,” said Rubini, who has taught dance at Union Mine for nine years. “There’s been no transparency as to where these funds have been disbursed. It’s just been crickets. … We feel like we’re being thrown under the bus.”

Rubini, who had just finished choreographing the school’s production of “Peter Pan,” says she was informed she would no longer be teaching dance next year. She has gathered 100 signatures from students who support the program and roughly a dozen students protested the cuts at a El Dorado Union High School District board meeting. They chanted “Music, dance and drama too. Save the arts for me and you.”

Union Mine principal Paul Neville has countered that the school is doing its best to meet student needs given declining enrollment and a shrinking budget.

“Enrollment in the dance program has decreased, while interest in drama has increased. In response to our students’ changing preferences, and the needs for other classes, we are adding theater sections,” he said. “We are exploring different ways to support this change and provide dance instruction within the theater program.”

Rubini is among a growing group of arts teachers concerned that some districts may be misspending their Proposition 28 money, using the new funds to pay for existing classes or activities outside the scope of arts education. In a letter to the governor, a coalition of arts education advocacy groups argue that school districts facing a budget crunch may be misapplying the funds.

“We are concerned that some school districts are making decisions without input from their communities and not complying with Prop 28,” the letter reads. “Some school districts are encouraging arts education teachers to resign, promising to rehire these teachers using Prop 28 funds.”

Teachers, students and parents throughout the state are asking where the money, which landed at schools in February, has gone, and why some arts programs are being cut.

“My biggest issue is that they are not only misusing the Prop. 28 funds, but at the same time cutting our performing arts programs dramatically,” said an arts teacher in Lake County, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “We have serious budget issues, but this is too much for me to take without a fight.”

While Proposition 28 was designed to prioritize hiring new arts teachers — most schools are required to use 80% of funds on staff — this teacher alleges the school is using the money to pay for electives it has long offered. Similarly, teachers unions have alleged that LAUSD, the state’s largest school district, has spent arts education money on other activities. Some parent advocates are also pushing for more transparency on how the funds are spent.

“When you look at the hours of arts instruction and they haven’t changed, how can you say arts instruction has increased?” said Rachel Wagner, the mother of a fourth grader at Encino Charter Elementary School and a leader of Parents Supporting Teachers, an advocacy group with roughly 40,000 members. “It’s very black and white in my mind.”

LAUSD officials maintain that overall arts education is up in the district. This year, the district budgeted $129.5 million toward the arts, in addition to $76.7 million from Proposition 28, for a total of more than $206 million. That’s roughly three times the $74.4 million that LAUSD spent on arts education in the previous academic year, according to a district news release.

At the core of Proposition 28 is the notion that funds are specifically designed to supplement, and not supplant, existing funding, which means that you can’t use the new money to pay for old programs. Former LAUSD Superintendent Austin Beutner, who authored the legislation, has characterized the law’s implementation so far as a C-minus.

“Some school districts either don’t wish to recognize the plain language of the law or are willfully violating the law,” Beutner said. “And they’re using money to backfill existing programs.”

Abe Flores, deputy director of policy and programs at Create CA, one of the advocacy groups that sent the letter, says that some school leaders may be unintentionally out of compliance with the law.

“Right now, we are in this phase of raising awareness,” he said. “We know principals are super busy. They have a lot of things on their plate. Proposition 28 may not be on their radar.”

The bottom line, Flores said, is if a school district is spending Proposition 28 funds but has not increased its arts staff, then by definition, it is violating the law. The coalition wants the state to make school districts prove they’ve hired more arts teachers, explain their plans for the future and get community input.

That’s precisely what Rubini and her department chair, Heather Freer, are calling for: greater accountability on how the money is spent going forward.

“Transparency isn’t just the right thing to do. It’s the law,” said Freer, visual and performing arts department chair at Union Mine. “We should be able to look at the budget and see where money is spent and see what’s going on.”

Budget cuts looming in the wake of the state’s deficit may be making matters worse for school administrators looking for stopgaps amid myriad troubles, including falling test scores, staffing shortages, chronic absenteeism and rampant misbehavior in the wake of the pandemic.

“Schools are looking for ways to save money,” said Jessica Mele, the interim executive director of Create CA, which advocates for high quality arts education. “In the absence of guidance from the CDE (California Department of Education), they will use the funds how they want.”

Another wrinkle may be that schools were intended to decide how to use the money, in response to the needs of their individual communities, but since the money gets funneled through the district, that hasn’t always happened.

To make matters worse, some say the CDE, which is administering the funds, has not provided enough guidance on how the rules work, leaving many in the dark about exactly what’s allowed and what’s not. For his part, Beutner has called for the state auditor to hold feet to the fire.

“Let’s be real; the only reason districts are cutting any arts positions now is because they think they can replace it with Prop 28 funds and get away with it,” said Beutner.

Thus far, the CDE has been offering guidance largely through webinars and FAQs designed to help districts best use the funding.

“CDE is aware of localized concerns about the use of funds,” said Elizabeth Sanders, a spokesperson for the department. “CDE takes such concerns very seriously and is working directly with district leaders to ensure that all statutory requirements are understood and followed. We are offering this support proactively and in partnership, to ensure that all of our students receive rich arts education opportunities.”

Sanders also said the department did not wish to interfere with the auditing process built into Proposition 28 accountability measures. The auditor will review all spending, and if the auditor finds that schools are misusing the money, they risk losing the funds.

Many have long argued that more oversight may be needed on how schools spend money, particularly during times of shrinking budgets.

“California school districts have been taking money for years that was provided for specific purposes and using it for other initiatives and the state Department of Education ignores it,” said Jack Jarvis, former adjunct faculty at Cal State Fresno and a veteran administrator. “There used to be a lot more oversight. Back when I became an administrator, there was much more scrutiny over school categorical funds.”

Some also argue that a lack of clarity on the complicated Proposition 28 rules might be partly to blame. For example, if a school is forced to cut its music program because of budget cuts, can it be revived the next year with Proposition 28 money? Would this run afoul of the supplant rule? Or could a waiver suffice? Many say the rules remain blurry.

“The Prop 28 rules seem clear enough on paper, but when you get into the weeds of budget development and the myriad of situations and circumstances that schools face in implementing an instructional program, they get far more fuzzy,” said Phil Rydeen, visual and performing arts director at Oakland Unified, which has long had a robust arts curriculum. “With little specific help from the CDE on the minutiae of Prop 28, it may indeed mean that districts will need to get through an audit to figure out what is actually permissible or not. In OUSD, we are being as conservative as we can be until we understand the impact of the Prop 28 rules.”

This lingering uncertainty over the rules is leading some schools to delay using the money.

“There are FAQs that sort of contradict one another,” said Letty Kraus, director of the California County Superintendents Arts Initiative. “If you look at FAQ 19, it says schools can pool resources and share staff, and FAQ 20 says you can’t reallocate funds to sites. So I can see how it would be confusing.”

Others believe that it may be more a matter of convenience than confusion. They say some administrators are playing fast and loose with the rules.

“They say that it is confusing legislation,” said Freer, who says the number of arts classes this year has remained the same despite the new money being spent. Next year, she says, there are even fewer arts classes planned. That adds up to less arts, she says, not more. “It is not confusing legislation. There is no lack of clarity.”

Flores, however, points out that ambiguities in the rules may exist.

“I wouldn’t go that far to say that they’re cheating,” said Flores. “I would say that there’s definitely some confusion and there’s definitely some wishful thinking in terms of the flexibility of the funds. There’s been a lot of confusion around some of the key points.”

Coupled with the fear of running afoul of state auditors, this cloud of uncertainty may have a chilling effect on the rollout at large, leading some schools to delay their pursuit of arts education just when children, still reeling from the aftershocks of the pandemic, need it most. Some arts educators are proceeding with caution, waiting to see how the rules are enforced before they proceed.

“Prop 28 is fraught with these kinds of problems,” Rydeen said. “It places well-meaning districts trying to maximize the impact of this resource with fidelity in a very difficult circumstance, hoping that they don’t guess incorrectly about applying the regulations.”

Many are calling for clearer and more explicit instructions before local education agencies (LEAs) are held accountable by audits.

“I suspect that lack of decisive guidance and being told to ‘consult legal counsel’ may be having a chilling effect for some LEAs who are understandably risk-averse,” said Kraus. “It would be helpful to have an accountability mechanism before the audit.”

For his part, Flores says his organization is not looking to play “gotcha” with schools, which are already overstressed and understaffed in the post-pandemic era, but instead to work with administrators to boost their arts education offerings.

“We want to be helpful,” he said. “We know most people want to do the right thing, and we want to create the situation, the resources, the awareness, the sharing of promising practices, so folks can do the right thing and and folks can plan and share their knowledge.”

For her part, Freer hopes she can raise awareness of just how vital dance is to many students. The class is crucial to keeping students engaged in school in the post-pandemic era, she says, when chronic absenteeism and apathy are running high.

“Especially at our school, the arts is a haven for our students who don’t have other reasons for coming to school,” said Freer. “We have a lot of kids who are at risk of disengaging from school. We hear it every day as arts teachers, (kids saying): ‘I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for you. I wouldn’t care if it wasn’t for you.’”

Some are also arguing that private philanthropy, such as parent donations, should not be counted as part of the baseline that can’t be supplanted because it is not funded by the state, not to mention variable.

Parents have labored long to raise enough donations to pay for a part-time art teacher in San Diego Unified, where Kimberly Cooper’s daughter attends a cash-strapped school. She and other parents were hoping that Proposition 28 would mean that hard-earned, parent-fundraised money could now go to raise the pay of the Spanish teacher, for instance.

“I am frustrated as a parent who has fundraised and donated for arts in our school,” Cooper said. “The issue of not supplanting parent fundraising isn’t just unfair, it’s impractical. It’s a struggle every year to meet our fundraising goals, because our limited sources are tapped out. We aren’t a school where parents can fundraise for a new donor-named auditorium.”

Some see this as an equity issue because richer communities will not have to fight as hard to raise funds year after year to meet the baseline. They are also far more likely to already have some expertise in how to develop arts education programs, which may exacerbate existing inequities in who has access to the arts.

Schools that have “disinvested in the arts over the years don’t have that expertise in-house, and they need help,” said Mele, the interim executive director of Create CA. “They’re struggling to know what kind of decisions to make… That’s where we see some inequities.”

Best practices for building an arts ed program from scratch is just one of many tricky issues that advocates are calling for more guidance on from the California Department of Education, which some say has been hard to pin down on many specifics, such as what constitutes good cause for a waiver and whether parent donations are counted against the baseline.

“Where the CDE could clarify but has not clarified is what constitutes baseline arts education funding at a school for the purposes of determining what is ‘supplanting’ versus ‘supporting’ existing arts education funds,” Mele said. “For example, do grant funds or PTA funds count? Or is it just state education dollars that count as the baseline? If PTA funds don’t count, then a school could use Prop 28 funds for arts programming that were formerly paid for with PTA funds and re-allocate PTA funds elsewhere.”

Proposition 28 author Beutner has long maintained that all funding should be counted as part of the baseline, but many are still waiting for the CDE to weigh in on the issue.

The “CDE has stayed silent on which funds ‘count’ as existing arts education funds,” said Mele, “leaving it up to schools and districts to figure this out by consulting their own legal counsel.”