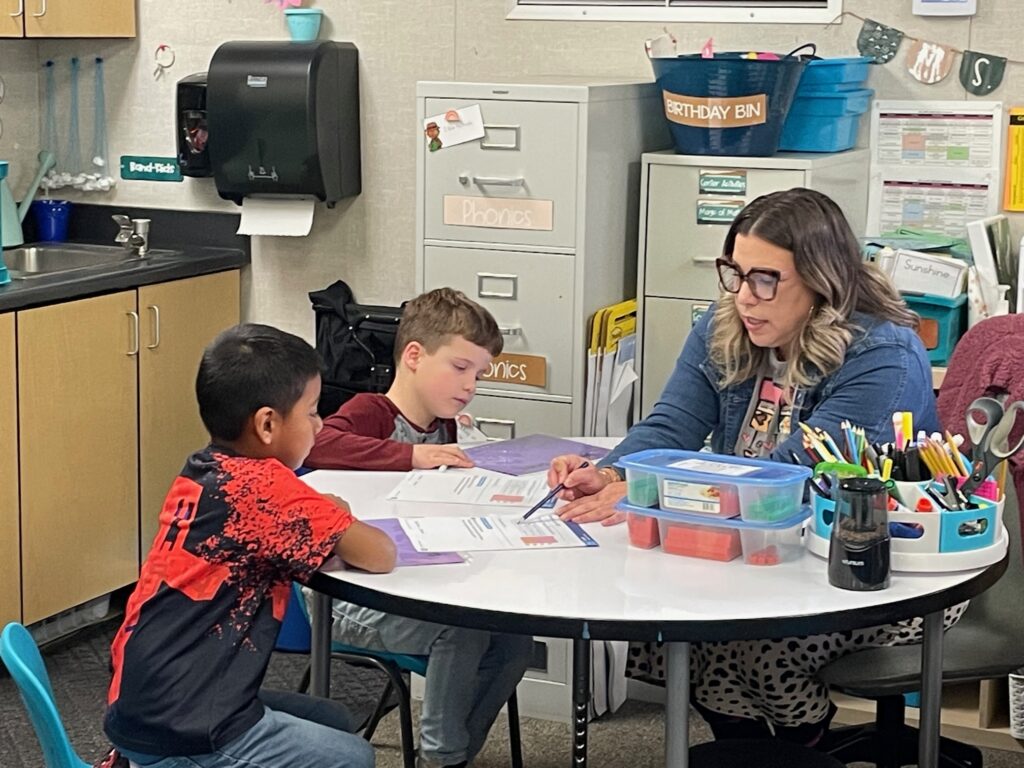

Teacher apprentice Ja’net Williams helps with a math lesson in a first grade class at Delta Elementary Charter School in Clarksburg, near Sacramento.

Credit: Diana Lambert / EdSource

Apprenticeships are being added to the long list of initiatives California has undertaken in recent years to address its enduring teacher shortage. State leaders hope that the free or reduced-priced tuition and steady salary that generally accompany apprenticeships will encourage more people to become teachers.

Apprentices complete their bachelor’s degree and a teacher preparation program while working as a member of the support staff at a school. They gain clinical experience at work while taking courses to earn their teaching credentials.

“It opens up the pipeline to teaching for folks who are hired into the school district,” said Joe Ross, president of Reach University, a nonprofit that operates a teacher apprenticeship program. “We have people at Reach who are in positions such as janitors, working in the lunchroom, working in the office. The majority are teacher’s aides, but you have this entirely larger, until now, really overlooked pool.”

California has joined 30 other states that have committed to launching registered teacher apprenticeship programs at the encouragement of the federal government. Last July, the Labor Department developed new national guidelines and standards for registered apprenticeship programs for K-12 teachers and provided funding to develop and expand programs. Twenty states have already started registered teacher apprenticeship programs.

Registered apprenticeship programs must be approved by either the Labor Department or a state apprenticeship agency. They offer a high-quality, rigorous pathway into a profession through an “earn-and-learn” model, according to the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency. The salaries of apprentices in these programs increase as they complete coursework and take on more responsibility.

Apprenticeships attract and retain candidates of color

Research shows that “grow your own” programs, such as apprenticeships, help to diversify the educator workforce because school staff recruited from the community more closely match the demographics of the student body than traditionally trained and recruited teachers. Apprenticeship programs also increase recruitment and have a 90% retention rate, according to the Labor Department.

“We know, for our candidates of color, that affordability is one of the key considerations,” said Shireen Pavri assistant vice chancellor of the Educator and Leadership Program at California State University.

Clinically rich preparation programs with mentorship, like apprenticeships and residencies, attract and retain more candidates of color, Pavri said. The candidates in these programs usually remain in the preparation program and with the school district they trained in, and stay in the field longer, she said.

Residencies, unlike apprenticeships, focus on teacher candidates who have already earned a bachelor’s degree and are new to the classroom.

“Apprenticeships are relatively new nationwide but really rapidly growing as a way to address teacher shortages,” Pavri said. “The Department of Labor has supported apprenticeships for quite a while, but not in teaching.”

Longtime school employee works toward dream job

On a recent Thursday, apprentice Ja’net Williams, 48, worked with small groups of first grade students as they rotated through a series of stations during a math lesson at Delta Elementary Charter School. She has worked as a paraeducator at the rural school in the tiny Delta town of Clarksburg, near Sacramento, for 14 years.

Williams has always wanted to be a credentialed elementary school teacher, but she couldn’t afford to enter a conventional preparation program. This year she joined the teaching apprenticeship program at Reach University.

Although it is not yet a registered apprenticeship program, which would allow it to access federal funding and resources, Reach University is currently one of the few programs in the state with an apprenticeship program preparing K-12 teachers.

As an apprentice, Williams continues to draw her salary as a paraeducator, and also earns, annually, a $2,300 stipend and is reimbursed up to $1,000 of her expenses from the school district. Reach University charges $75 a month for tuition.

“I was looking at different options,” she said. “It came down to, it’s affordable. I’m a mom. I have a daughter in Sac State and one that will be starting at Sac City (College) next year. So I want to help them financially as much as possible, and take off the burden for them. So I couldn’t take on, you know, $40,000 of debt for myself when I would want to put that toward my children.”

Williams works in the classroom during the day and takes classes on Zoom two evenings a week to complete her bachelor’s degree and teacher preparation courses. She and her classmates discuss their day’s experiences and incorporate them into their coursework, Williams said.

After completing her teaching credential, Williams plans to continue to work at Delta Elementary Charter as a teacher. “I want to stay here,” she said. “This is where my heart and soul is.”

Experts plan state teacher apprenticeship program

There are 17 registered teaching apprenticeship programs in California, but they are mostly limited to early childhood education. There are no registered apprenticeships for K-12 credentialed teachers, said Erin Hickey, a spokesperson for the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency.

They may be more common soon. Pavri is part of a group of educators, researchers, state and county officials, and labor and policy representatives who have been working with the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency and the Division of Apprenticeship Standards for nearly a year to develop a Roadmap for Teacher Apprenticeships for California. Their work is being funded with philanthropic support.

The road map will help school districts, teacher preparation programs and other partners navigate the process and find funding to launch, scale and sustain registered teacher apprenticeship programs, Hickey said. The road map is expected to be released later this year.

The road map will take into consideration multiple on-ramps and pathways for different teacher candidates, including high school students, post-secondary students, current classified staff and other career changers, Hickey said.

Preparing the road map hasn’t been easy, Pavri said. The work group has had to clarify and streamline regulations from both the California Division of Apprenticeship Standards and the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. The agencies are working together to develop a joint approval process that will be informed by the work group and by pilot programs expected to begin next school year.

San Diego, Los Angeles, Fresno, Sacramento and the Bay Area have been identified as potential pilot locations, according to Hickey.

The work group is also trying to identify a sponsor for the state program from a university, county office of education or state agency, or a consortium of partners, Pavri arvi said.

“Without adequate funding, it’s going to be really hard to ask for existing staff to take on these responsibilities,” Pavri said. “So, we’ve been trying to figure out what the roles and responsibilities for each of these entities are, and what kinds of funding would be available to administer the program.”

Funding for teacher recruitment drying up

California has spent more than $1.2 billion since 2016 to address teacher shortages, including $170 million for the California Classified School Employee Credentialing program, which also helps school staff to earn a degree and teaching credential. But budget shortfalls have state leaders looking for other sources of funding to grow the teacher workforce and to help teacher candidates to get paid while they learn, Pavri said.

Registered apprenticeship programs receive federal funding through the Department of Labor.

“Here in California, there have been recent incredible state investments for us to grow and diversify our teacher workforce,” Pavri said. “But all of these funds are one-time legislative appropriations. And then we’re also concerned about the health of the state budget and whether these appropriations would be renewed.”