Credit: Pexels

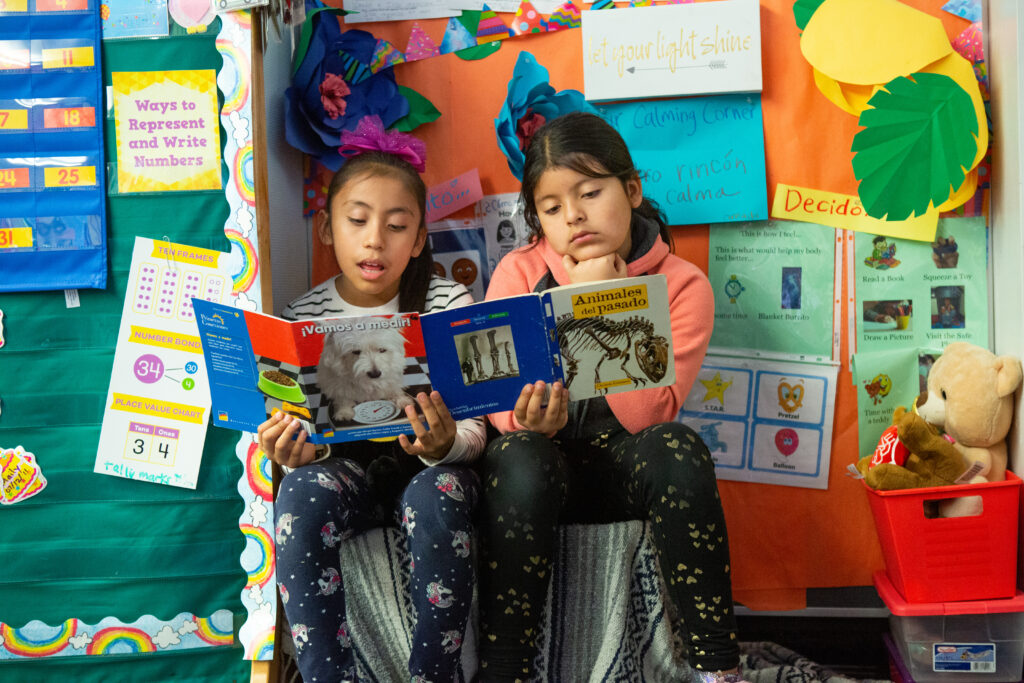

For nearly 20 years, academic strategies, support and policies focused on closing long-standing achievement gaps in STEM between boys and girls. These efforts paid off, and by 2019, girls’ achievement in math and science equaled or exceeded boys’. Then the pandemic hit, and the gaps that took two decades to close were back.

My colleagues and I at NWEA, an education assessment and research company, examined how the pandemic impacted achievement for boys and girls in math and science. We looked at scores from three large national assessments (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, the National Assessment of Educational Progress and NWEA’s MAP Growth). The data highlighted two main trends:

- The achievement gap in math and science reemerged during the pandemic, once again favoring boys. However, an achievement gap did not resurface in reading, where girls continue to outperform boys.

- Looking at high-achieving students, boys showed significantly higher scores across assessments than girls in both math and science. For low-achieving students, however, boys’ scores were lower than girls’.

These trends are not limited to the U.S. Other English-speaking countries show similar gaps, pointing to a broader issue. A similar trend is seen more locally. On the NAEP assessments, which provide California-specific data for eighth grade math, the results mirror the nation. In 2019, California boys and girls had an average math score that was not significantly different. By 2024, however, boys had an average score that was 6 points higher than girls’ in math.

Our research also looked at enrollment by boys and girls in eighth grade algebra across 1,300 U.S. schools. Enrollment in this math course is often used as a predictor of future enrollment in higher-level math in high school, as well as a predictor of participation in college and career opportunities in STEM fields. In 2019, girls enrolled at higher levels than boys in eighth grade algebra (26% vs 24%). By 2022, enrollment had declined for both groups, with the drop-off for girls being slightly sharper than for boys. While the decline was experienced by both, enrollment for boys in algebra had bounced back to pre-pandemic levels by 2024.

Taken together, the results of this research signal that the effects of the pandemic were not felt evenly by boys and girls. More significantly, this data does not provide the “why” for these setbacks and the reemergence of achievement gaps. One area to spotlight is the trend of girls reporting more emotional challenges, like depression and anxiety, during and after the pandemic that may have impacted their learning. Notably, the widening gender gap emerged after students returned to in-person school, pointing to factors in the school environment as potential contributors, like the reports of rising behavioral issues among boys, leading teachers to pay more attention to them in class.

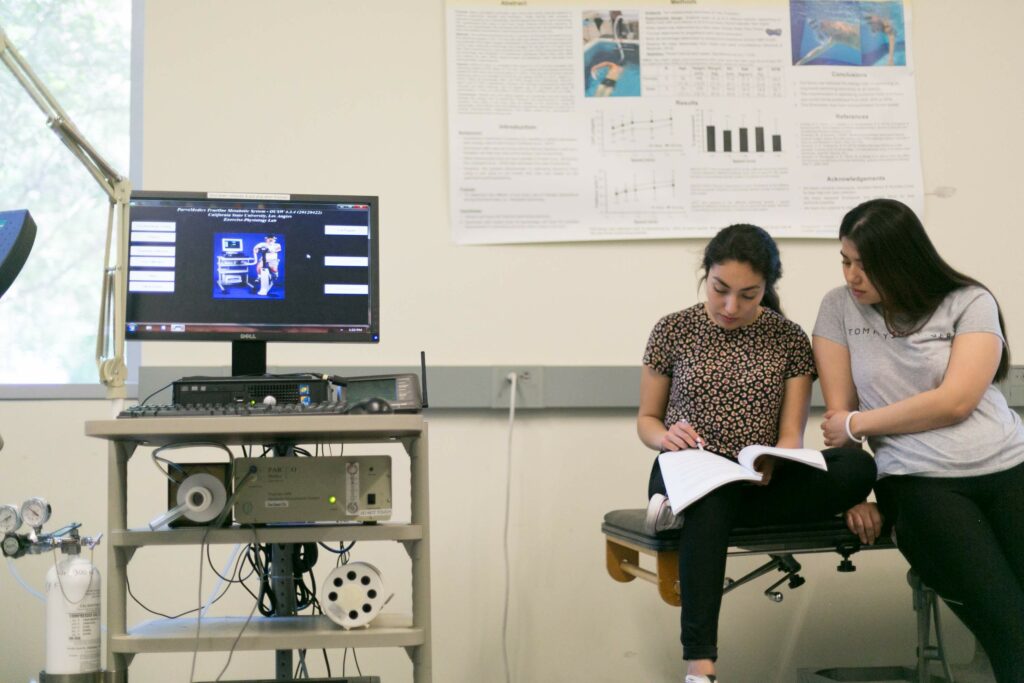

While many of the concerns in the last few years about gender differences in school have focused on the ways that boys are struggling more than girls, our research has illustrated an overlooked area where girls could use more support. As schools continue to focus on academic recovery and approaches that drive academic outcomes for all students, it’s crucial that those efforts are measured and evaluated effectively to ensure new inequities don’t arise or old ones don’t take permanent root. We have three primary recommendations to address these gaps:

- Monitoring participation in STEM milestones by boys and girls, over time, and not just within a single year to gain a better view of trends. For example, eighth grade algebra enrollment in 2024 appears to be balanced by gender, but it overlooks a critical trend that boys’ enrollment has returned to pre-pandemic levels while girls’ enrollment is still below 2019 levels. Analyzing longitudinal trends within each group is key to uncovering and addressing setbacks that may be hidden by a single-point-in-time snapshot.

- Providing specific academic and emotional support to students. Girls reported feeling more stress, anxiety and depression than boys, and noted it as an obstacle to their learning during the pandemic. Addressing both the academic needs and emotional needs of students may be critical in closing these emerging gaps in STEM skills.

- Evaluating classroom dynamics and instructional practices. If shifts in behavior and teacher attention during the pandemic disproportionately benefited boys in STEM subjects, understanding these shifts may help address the re-emerged achievement gap. Targeted professional learning that promotes equitable participation and inclusive teaching practices in STEM can help ensure all students have equal opportunities to succeed.

As our schools continue to navigate this long path toward academic recovery, it’s important that those efforts don’t unintentionally grow existing inequities or create new ones. More and more evidence is emerging that the pandemic was not an equal opportunity hitter, and its disruptions affected students differently. For girls in math and science, moving forward will require renewed attention to addressing achievement gaps, targeted support and careful monitoring of progress. Reclosing STEM gaps will take time, but with the right focus, it is possible to not only recover, but to build a more equitable STEM education system that ensures both boys and girls have immense opportunities to succeed.

•••

Megan Kuhfeld is the director of growth modeling and analytics for NWEA, a division of the adaptive learning company HMH, which supports students and educators in more than 146 countries through research, assessment solutions, policy and advocacy, and professional learning.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.