California may have low public college tuition costs when compared to other colleges and universities nationally, but it is not enough to prevent students from taking high amounts of student loans.

A new study released exclusively to EdSource from The Century Foundation found Californians have higher average student debt balances, risky graduate school debt, a unique reliance on parent-held debt and significantly high student debt among Black families.

California’s high cost of living makes debt inevitable for many students, but the risk is greater for students from lower-income families and communities of color eager to use education as a ladder into the middle class. Open-ended loans aimed at parents and graduate students are particularly burdensome, including those used to attend for-profit colleges.

Despite having a smaller share of student loan borrowers when compared with other states, California’s borrowers are in the top third among states, with an average of $37,400 owed, according to national data from June 2022. That figure includes all borrowers, regardless of whether they attended college in California. The state ranks 16th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia for borrowers with high balances. This is despite having the fourth-lowest rate of student borrowers.

“One of California’s great successes is in college affordability and the fact that so many students go through college without debt,” said Peter Granville, a fellow at the foundation studying federal and state policy efforts to improve college affordability and author of the study. “Unfortunately, the Californians who do borrow take out some of the most risky debt around.” The foundation is a progressive, independent think tank that researches and promotes policy change to foster equity.

Besides the impact on individuals, student loan debt has become a larger problem for the American economy. Nationally, the current student loan debt totals $1.77 trillion.

“Student debt is something that is different from what it was 10 or 20 years ago,” U.S. Undersecretary of Education James Kvaal told higher education reporters earlier this month at UC Riverside. “People are borrowing more. They’re struggling more with those loans. It’s not just a problem for the 43 million Americans with student loan debt when they cannot afford to buy a house, start a new business or save for their own children or their retirement. It’s a problem for their families. It’s a problem for their communities. It’s a problem for our economy. It’s a fundamental crisis that we have to address in our country. We have to change how we’re financing higher education.”

Loan repayments restarting in October

With the Supreme Court rejecting President Joe Biden’s attempt to forgive $20,000 in loans for millions of borrowers, many are preparing to restart repayments in October. The situation underscores a larger student loan crisis in California and across the country. Millions of people, including those who never graduated from college and parents, are carrying student loan debt that they cannot afford and realistically may not ever pay back.

“Californians really struggle with repayment,” Granville said. “The state economy demands a college education, and I believe that demand drives up borrowing.”

And the situation is worse for graduates and families that borrow from the federal Parent PLUS and Grad PLUS loan programs that allow parents to borrow on behalf of their college students and graduate students to afford higher degrees, Granville said, adding that both programs offer high-interest, uncapped loans.

“These loans are probably the worst things to dangle in front of families with real genuine fears of being left behind economically,” he said. “But that leads to high balances that are difficult to manage.”

Graduate loan debt is larger in California than in the rest of the country, the study found. The state’s average annual Grad Plus loan is 25% higher than the rest of the country. In-state graduate students borrow on average $28,300 in loans each year compared with $22,400 nationally.

California places a premium on higher education in the state, Granville said. The average California worker with a graduate degree earns $108,500 – a 50% increase above the average income for bachelor’s degree holders.

The state also sees a disproportionate share of Black students borrowing student loans. In the 2015-16 academic year, 28% of Black in-state undergraduates borrowed loans compared with 21% of all undergraduates. At the graduate level, 81% of Black Californians took out student loans compared to 51% of all other graduate students.

“High borrowing among Black students in California locks in inequality that can last long into repayment,” Granville said. “Despite having a college degree and living in a higher income state, Black borrowers in California actually show worse financial security.”

Black women undergraduates borrow at the highest rates in any one year, with 31% taking loans in 2015-16 compared with 21% of all undergraduates, according to the study.

Granville said the data reflects the racial wealth gap.

“Black families have fewer financial resources than white families,” he said. “That leads to it being a lot harder to ask a Black family to self-finance education without debt. Homeownership also matters. You can take out a home equity loan for a much lower rate than a Parent Plus loan, for example.”

Latinos follow Black borrowers but with not as high graduate loan debt at 62%. But Latino families also have concerning trends. The majority of Latino borrowers in California don’t have a college degree, while only one-quarter of white borrowers don’t. The report explains that this could be due to a greater share of Latinos leaving college before they earn a degree or higher shares of parents borrowing on behalf of their children.

Granville said the state should examine whether all California families are “being potentially set up to fail.”

“Lawmakers should be looking at the colleges within California and asking, are colleges passing on high costs to students knowing that they can take out this uncapped loan debt?” he said. “I worry about how some loans are being sold to students by their colleges. Unless families are getting wise counsel, they may be unknowingly signing up for a pretty tough repayment experience.”

The racial wealth gap, along with California’s cost of living, makes it particularly challenging for Californians to pay their student debt, Granville said.

Repaying more than $200,000

In many ways, Richelle Brooks is a college success story. She’s also an outlier in the student debt crisis.

Credit: Courtesy of Richelle Brooks

Richelle Brooks

A first-generation college student, Brooks earned an associate degree from El Camino College, then went on to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Cal State Dominguez Hills. She graduated with her doctorate in 2018 from Cal State Los Angeles.

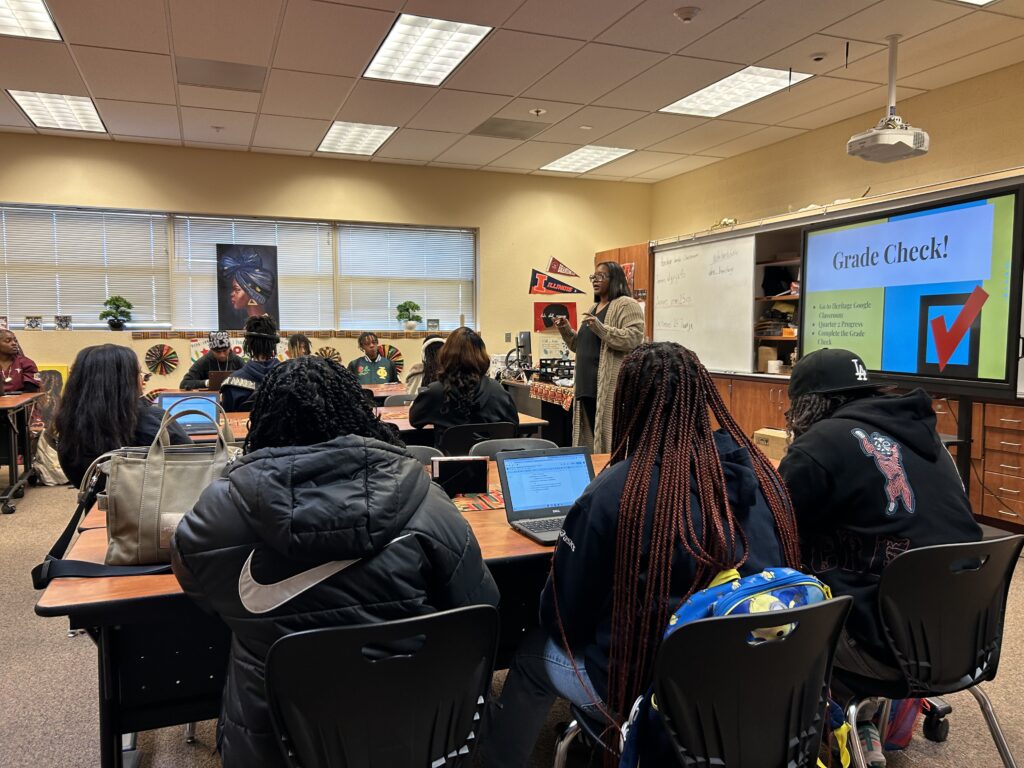

Now, as a Los Angeles-area high school principal, she mentors and educates low-income students and students of color. She’s also facing more than $237,000 of student loan debt. The mom of three can’t fathom repaying it all, even with her $120,000 annual salary.

Enrolling in community colleges even after graduating with her doctorate, as well as the three-year pandemic pause, allowed her to put off making payments. But that could be coming to an end.

Brooks, who advocates for student loan forgiveness, participates in one of the federal government’s income-driven repayment plans, which slowly escalates her monthly payments based on her income as a high school principal. Her first payment, which restarts in October, is for $700. But by June 2024 it will increase to $2,600 a month.

“I ran the numbers,” Brooks, 36, said. “It’ll be cheaper to stay in school the rest of my life than to pay that $200,000.” (Federal loan repayments pause while a person is enrolled in school.)

About $33,000 of Brooks’ debt is just from interest that accumulated over the years. But because of the interest, Brooks said that her ability to pay off the debt “doesn’t exist.”

“On paper, it sounds like I make a lot of money,” she said. “But they’re not taking into consideration that I live in LA and I have three kids.”

Brook’s partner is a military veteran and teacher. He doesn’t have student loans because of his military service, but the couple found they’re unable to purchase a home for their family because of Brook’s debt-to-income ratio, a situation that affects many student borrowers. Brooks also supports her mother, who lives with the family after facing homelessness.

California’s high cost of living makes it difficult for young people coming out of college without significant family resources to accumulate assets like a home, especially if they have student loan debt. In California, 78% of Black households with student debt and 74% of Latino households with student debt have less than $50,000 in savings and investments, compared with 57% of white households with student loans, according to The Century Foundation.

In addition to her work as a principal, Brooks said she’s taken on other jobs to make ends meet, including driving Uber, and that’s before the loan repayments begin.

“Whatever it takes to make sure my kids have what they need and the bills are paid,” she said.

Brooks’ two oldest children are in high school and affording college is a common discussion in their home.

“I do not foresee a way for me to pay off my debt and figure out a way to pay my kids’ college, and I do not want them to go into debt,” she said. “I talked to my daughter about joining the military, but it’s kind of terrifying too because she’s a little Black girl. … So I’m trying to figure it out.”

As an educator, Brooks could apply for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, which she is considering once again. The program typically forgives the debt of people who work for a government or nonprofit employer, such as teachers, first responders and nurses. But forgiveness isn’t granted until after the borrower makes 120 or 10 years of payments.

Restarting repayments

Although Brooks’ debt amounts are larger than the average of most borrowers, her struggle to repay her college loans is common.

“In the popular imagination, there is this idea that student debt is a young people issue,” said Thomas Gokey, an organizer and co-founder of The Debt Collective, a union of advocates for publicly funded college, universal health care and guaranteed housing. “The truth is that the debt just doesn’t go away.”

People age, have children, grandchildren, and careers decades removed from graduation, and the “debt is still there,” Gokey said, adding that for many people, the monthly payments don’t cover the interest.

Some people have fully paid back their principle multiple times over, with the outstanding balance higher than the original balance. Other people may fall on hard times and can’t make payments, which leads to massive penalties, he said, referring to one case where a borrower defaulted on her student loan during the 2008 financial crisis and saw a $10,000 penalty added to her balance.

For undergraduates, even when their financial aid forms say they have $0 in expected family contributions, the cost of college attendance and tuition has increased to the point where aid doesn’t cover everything, he said. “The only option is Parent Plus loans to fill the gap. It’s just astonishing that a lot of parents will be paying off the loans for a longer period of time than they lived with or raised the children that they got the loan for.”

Granville said many, trying to get ahead, take on more loans after undergraduate loans.

“Students often turn to graduate education when they’re struggling with their undergraduate loans,” he said. “They may see the next degree as the thing that will give them the earning power to handle the debt that they have struggled with already.”

There is a misperception that a graduate degree means a person will be “really successful” and “make a lot of money,” Gokey said. “And that’s just not true if you’re a social worker,” he added, as an example of a lower salary job.

According to The Century Foundation’s data, a social worker with a bachelor’s degree earns on average $34,183 one year after completing their program, but has an average $15,599 in student loans. A social worker with a master’s degree earns an average of $54,223 one year after completing their program, but has on average nearly $80,000 in student loans. Licensed clinical social workers in California are required by the state to have a master’s degree in social work.

Gokey said that there’s no way to “financial literacy yourself” out of student loan debt.

Options and fixes

Although interest rates restarted in September and repayments resume in October, the federal government is giving borrowers a one-year grace period as it attempts to fix the loan system and offer solutions that significantly lower monthly payments.

“We really inherited a student loan system that was broken,” Kvaal said. “Before the student loan pause, we had a million students a year defaulting on their student loans.”

Kvaal said those defaults weren’t from people running from their responsibilities, but borrowers struggling with payments. Many of them were first-generation or students of color, he said.

| Institution name | Type | Stafford (undergraduate) | Parent PLUS | Grad PLUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy of Art University | For-profit | 37% | 30% | 42% |

| Advanced Career Institute | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Allan Hancock College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Alliant International University-San Diego | For-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| American Academy of Dramatic Arts-Los Angeles | Non-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| American Career College-Los Angeles | For-profit | 34% | 21% | n/a |

| American Career College-Ontario | For-profit | 37% | 32% | n/a |

| American College of Healthcare and Technology | For-profit | 51% | n/a | n/a |

| American River College | Public | 44% | n/a | n/a |

| Angeles Institute | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Antelope Valley College | Public | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| Antioch University-Los Angeles | Non-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Art Center College of Design | Non-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Asher College | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Ashford University | For-profit | 46% | 37% | 44% |

| Associated Technical College-Los Angeles | For-profit | 49% | n/a | n/a |

| Associated Technical College-San Diego | For-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Avalon School of Cosmetology-Alameda | For-profit | 41% | n/a | n/a |

| Aveda Institute-Los Angeles | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Azusa Pacific University | Non-profit | 25% | 16% | 42% |

| Bakersfield College | Public | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| Bard College – MAT Program CA | Non-profit | 24% | 17% | n/a |

| Bellus Academy-Chula Vista | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Bellus Academy-El Cajon | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Bellus Academy-Poway | For-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Berkeley City College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Bethel Seminary-San Diego | Non-profit | 18% | 22% | 36% |

| Biola University | Non-profit | 20% | 22% | 32% |

| Blake Austin College | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Brandman University | Non-profit | 31% | n/a | 39% |

| Brownson Technical School | For-profit | 17% | n/a | n/a |

| Butte College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Cabrillo College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| California Aeronautical University | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| California Baptist University | Non-profit | 31% | 30% | 43% |

| California Career Institute | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| California College of the Arts | Non-profit | 26% | 32% | 47% |

| California College San Diego | Non-profit | 44% | n/a | n/a |

| California Hair Design Academy | For-profit | 26% | n/a | n/a |

| California Healing Arts College | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| California Institute of Integral Studies | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| California Institute of the Arts | Non-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| California Lutheran University | Non-profit | 22% | 26% | n/a |

| California Nurses Educational Institute | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo | Public | 12% | 14% | 24% |

| California State Polytechnic University-Pomona | Public | 21% | 22% | 38% |

| California State University Maritime Academy | Public | 17% | n/a | n/a |

| California State University-Bakersfield | Public | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| California State University-Channel Islands | Public | 22% | 17% | n/a |

| California State University-Chico | Public | 23% | 22% | n/a |

| California State University-Dominguez Hills | Public | 27% | n/a | 32% |

| California State University-East Bay | Public | 25% | 22% | 35% |

| California State University-Fresno | Public | 24% | n/a | 34% |

| California State University-Fullerton | Public | 20% | 27% | 29% |

| California State University-Long Beach | Public | 20% | 22% | 37% |

| California State University-Los Angeles | Public | 23% | n/a | 37% |

| California State University-Monterey Bay | Public | 24% | 17% | 37% |

| California State University-Northridge | Public | 22% | 17% | 37% |

| California State University-Sacramento | Public | 24% | 20% | 36% |

| California State University-San Bernardino | Public | 27% | 22% | 40% |

| California State University-San Marcos | Public | 23% | n/a | n/a |

| California State University-Stanislaus | Public | 23% | 17% | 36% |

| California Western School of Law | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Cambridge Junior College-Yuba City | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Career Academy of Beauty | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Career Care Institute | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Career Networks Institute | For-profit | 33% | n/a | n/a |

| Carrington College-Sacramento | For-profit | 37% | 20% | n/a |

| Casa Loma College-Van Nuys | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| CBD College | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Central Coast College | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Cerritos College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| CET-San Diego | Non-profit | 40% | n/a | n/a |

| Chabot College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Chamberlain University-California | For-profit | 26% | 24% | 30% |

| Chapman University | Non-profit | 20% | 18% | n/a |

| Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 37% |

| Cinta Aveda Institute | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Citrus College | Public | 33% | n/a | n/a |

| City College of San Francisco | Public | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| Claremont Graduate University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Coastline Community College | Public | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| Cogswell University of Silicon Valley | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| College of Marin | Public | 51% | n/a | n/a |

| College of the Canyons | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| College of the Redwoods | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| College of the Sequoias | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| College of the Siskiyous | Public | 45% | n/a | n/a |

| Columbia College – Los Alamitos | Non-profit | 39% | n/a | 38% |

| Columbia College Hollywood | Non-profit | 39% | 32% | n/a |

| Concorde Career College-Garden Grove | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Concorde Career College-North Hollywood | For-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Concorde Career College-San Bernardino | For-profit | 35% | n/a | n/a |

| Concorde Career College-San Diego | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Concordia University-Irvine | Non-profit | 22% | 27% | 27% |

| Contra Costa College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Cosumnes River College | Public | 45% | n/a | n/a |

| Cuesta College | Public | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| Culinary Institute of America at Greystone | Non-profit | 24% | 33% | n/a |

| Cypress College | Public | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| De Anza College | Public | 34% | n/a | n/a |

| Design’s School of Cosmetology | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| DeVry University-California | For-profit | 42% | 29% | 40% |

| Diablo Valley College | Public | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Diversified Vocational College | For-profit | 51% | n/a | n/a |

| Dominican University of California | Non-profit | 20% | n/a | 37% |

| East Los Angeles College | Public | 33% | n/a | n/a |

| Empire College | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Feather River Community College District | Public | 41% | n/a | n/a |

| Federico Beauty Institute | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| FIDM-Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising-Los Angeles | For-profit | 30% | 32% | n/a |

| Fielding Graduate University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 37% |

| Folsom Lake College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Foothill College | Public | 35% | n/a | n/a |

| Fremont College | For-profit | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| Fresno City College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Fresno Pacific University | Non-profit | 28% | n/a | 38% |

| Fuller Theological Seminary | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Fullerton College | Public | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Glendale Career College | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Glendale Community College | Public | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Golden Gate University-San Francisco | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Golden West College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Grossmont College | Public | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| Gurnick Academy of Medical Arts | For-profit | 25% | n/a | n/a |

| Harvey Mudd College | Non-profit | 8% | n/a | n/a |

| High Desert Medical College | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Holy Names University | Non-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Homestead Schools | Non-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Hope International University | Non-profit | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| Humboldt State University | Public | 29% | 22% | 37% |

| Humphreys University-Stockton and Modesto Campuses | Non-profit | 41% | n/a | n/a |

| Hussian College-Los Angeles | For-profit | 53% | n/a | n/a |

| Institute for Business and Technology | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Institute of Culinary Education | For-profit | 19% | n/a | n/a |

| Institute of Technology | For-profit | 43% | n/a | n/a |

| InterCoast Colleges-Santa Ana | For-profit | 40% | n/a | n/a |

| International School of Beauty Inc | For-profit | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| International School of Cosmetology | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Irvine Valley College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| John F. Kennedy University | Non-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| La Sierra University | Non-profit | 33% | 27% | n/a |

| Laguna College of Art and Design | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Laney College | Public | 47% | n/a | n/a |

| Laurus College | For-profit | 53% | n/a | n/a |

| Life Chiropractic College West | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 47% |

| Life Pacific University | Non-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Loma Linda University | Non-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Long Beach City College | Public | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Center | Non-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles City College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Film School | For-profit | 47% | 37% | n/a |

| Los Angeles Mission College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Pierce College | Public | 40% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Southwest College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Trade Technical College | Public | 39% | n/a | n/a |

| Los Angeles Valley College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Loyola Marymount University | Non-profit | 17% | 24% | n/a |

| Lu Ross Academy | For-profit | 26% | n/a | n/a |

| Make-up Designory | For-profit | 19% | 22% | n/a |

| Marshall B Ketchum University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 32% |

| Marymount California University | Non-profit | 35% | n/a | n/a |

| Mayfield College | For-profit | 39% | n/a | n/a |

| Mendocino College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Menlo College | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Merritt College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Miami Ad School-San Francisco | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey | Non-profit | 14% | n/a | n/a |

| Milan Institute of Cosmetology-Fairfield | For-profit | 49% | n/a | n/a |

| Milan Institute-Fresno | For-profit | 46% | n/a | n/a |

| Milan Institute-Palm Desert | For-profit | 45% | n/a | n/a |

| Milan Institute-Visalia | For-profit | 34% | n/a | n/a |

| Mills College | Non-profit | 26% | n/a | n/a |

| MiraCosta College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Moler Barber College | For-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Monterey Peninsula College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Moorpark College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Moreno Valley College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Mount Saint Mary’s University | Non-profit | 28% | 17% | n/a |

| Mt San Antonio College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| MTI College | For-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Musicians Institute | For-profit | 35% | 32% | n/a |

| National Career College | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| National Holistic Institute | For-profit | 28% | n/a | n/a |

| National University | Non-profit | 32% | n/a | 39% |

| New York Film Academy | For-profit | 35% | n/a | n/a |

| North Adrian’s College of Beauty Inc | For-profit | 46% | n/a | n/a |

| Northcentral University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 37% |

| North-West College-Pomona | For-profit | 24% | n/a | n/a |

| North-West College-Van Nuys | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| North-West College-West Covina | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Notre Dame de Namur University | Non-profit | 26% | 32% | 47% |

| NTMA Training Centers of Southern California | Non-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Occidental College | Non-profit | 14% | n/a | n/a |

| Orange Coast College | Public | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Otis College of Art and Design | Non-profit | 27% | 32% | n/a |

| Pacific College | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Pacific College of Health and Science | For-profit | 42% | n/a | 47% |

| Pacific Oaks College | Non-profit | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| Pacific Union College | Non-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Pacifica Graduate Institute | For-profit | n/a | n/a | 47% |

| Palo Alto University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 47% |

| Palomar College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Palomar Institute of Cosmetology | For-profit | 22% | n/a | n/a |

| Pasadena City College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-East Bay | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Fresno | For-profit | 41% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Modesto | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Pasadena | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Sacramento | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Sherman Oaks | For-profit | 27% | n/a | n/a |

| Paul Mitchell the School-Temecula | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Pepperdine University | Non-profit | 20% | 22% | 39% |

| Pima Medical Institute-Chula Vista | For-profit | 29% | 20% | n/a |

| Pitzer College | Non-profit | 17% | n/a | n/a |

| Platt College-Los Angeles | For-profit | 34% | n/a | n/a |

| Point Loma Nazarene University | Non-profit | 19% | 27% | n/a |

| Premiere Career College | For-profit | 29% | n/a | n/a |

| Reedley College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Relay Graduate School of Education – California | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 37% |

| Riverside City College | Public | 34% | n/a | n/a |

| Sacramento City College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Saddleback College | Public | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| SAE Expression College | For-profit | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Saint Mary’s College of California | Non-profit | 19% | 37% | 32% |

| Salon Success Academy-Corona | For-profit | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Salon Success Academy-Upland | For-profit | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Samuel Merritt University | Non-profit | 8% | n/a | 36% |

| San Diego Christian College | Non-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| San Diego City College | Public | 41% | n/a | n/a |

| San Diego Mesa College | Public | 33% | n/a | n/a |

| San Diego Miramar College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| San Diego State University | Public | 21% | 16% | 38% |

| San Francisco Art Institute | Non-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| San Francisco Institute of Esthetics & Cosmetology Inc | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| San Francisco State University | Public | 24% | 22% | 35% |

| San Joaquin Delta College | Public | 46% | n/a | n/a |

| San Joaquin Valley College-Visalia | For-profit | 42% | 22% | n/a |

| San Jose City College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| San Jose State University | Public | 18% | 14% | 33% |

| Santa Ana College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Santa Barbara Business College-Bakersfield | For-profit | 45% | n/a | n/a |

| Santa Barbara Business College-Santa Maria | For-profit | 34% | n/a | n/a |

| Santa Barbara City College | Public | 36% | n/a | n/a |

| Santa Clara University | Non-profit | 9% | 27% | n/a |

| Santa Monica College | Public | 33% | n/a | n/a |

| Santa Rosa Junior College | Public | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Saybrook University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 37% |

| Shasta College | Public | 39% | n/a | n/a |

| Sierra College | Public | 40% | n/a | n/a |

| Simpson University | Non-profit | 20% | n/a | n/a |

| Solano Community College | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Sonoma State University | Public | 21% | 14% | 37% |

| South Baylo University | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Coast College | For-profit | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Southern California Health Institute | For-profit | 39% | n/a | n/a |

| Southern California Institute of Technology | For-profit | 23% | n/a | n/a |

| Southern California University of Health Sciences | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 47% |

| Southwestern College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Southwestern Law School | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Spartan College of Aeronautics & Technology | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| Stanbridge University | For-profit | 20% | n/a | n/a |

| Stanford University | Non-profit | 12% | n/a | 17% |

| SUM Bible College and Theological Seminary | Non-profit | 47% | n/a | n/a |

| Summit College | For-profit | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| The Chicago School of Professional Psychology at Anaheim | Non-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| The Master’s University and Seminary | Non-profit | 12% | n/a | n/a |

| Thomas Jefferson School of Law | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Touro University California | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Touro University Worldwide | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | 32% |

| Trident University International | For-profit | 32% | n/a | 33% |

| Trinity Law School | Non-profit | 31% | n/a | 38% |

| UEI College-Fresno | For-profit | 50% | 37% | n/a |

| UEI College-Gardena | For-profit | 46% | 22% | n/a |

| United Education Institute-Huntington Park Campus | For-profit | 45% | 37% | n/a |

| United States University | For-profit | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| Unitek College | For-profit | 21% | 17% | n/a |

| Universal Technical Institute of California Inc | For-profit | 37% | 22% | n/a |

| Universal Technical Institute of Northern California Inc | For-profit | 38% | 22% | n/a |

| University of Antelope Valley | For-profit | 31% | n/a | n/a |

| University of California-Berkeley | Public | 13% | 14% | 30% |

| University of California-Davis | Public | 12% | 13% | 37% |

| University of California-Hastings College of Law | Public | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| University of California-Irvine | Public | 15% | 14% | 37% |

| University of California-Los Angeles | Public | 15% | 18% | 33% |

| University of California-Merced | Public | 20% | 18% | n/a |

| University of California-Riverside | Public | 22% | 19% | n/a |

| University of California-San Diego | Public | 13% | 12% | 31% |

| University of California-San Francisco | Public | n/a | n/a | 32% |

| University of California-Santa Barbara | Public | 16% | 19% | 28% |

| University of California-Santa Cruz | Public | 20% | 18% | 32% |

| University of La Verne | Non-profit | 30% | 27% | 41% |

| University of Phoenix-California | For-profit | 43% | 35% | 42% |

| University of Redlands | Non-profit | 27% | 27% | 38% |

| University of San Diego | Non-profit | 16% | 24% | n/a |

| University of San Francisco | Non-profit | 19% | 22% | 41% |

| University of Southern California | Non-profit | 16% | 25% | n/a |

| University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences | For-profit | n/a | n/a | 32% |

| University of the Pacific | Non-profit | 19% | 22% | n/a |

| Vanguard University of Southern California | Non-profit | 26% | 27% | n/a |

| Ventura College | Public | 37% | n/a | n/a |

| Victor Valley College | Public | 46% | n/a | n/a |

| West Coast Ultrasound Institute | For-profit | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| West Coast University-Los Angeles | For-profit | 25% | 30% | 32% |

| West Hills College-Coalinga | Public | 47% | n/a | n/a |

| West Hills College-Lemoore | Public | 42% | n/a | n/a |

| West Los Angeles College | Public | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Western University of Health Sciences | Non-profit | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Westmont College | Non-profit | 12% | n/a | n/a |

| Whittier College | Non-profit | 29% | 32% | n/a |

| William Jessup University | Non-profit | 24% | n/a | n/a |

| Woodbury University | Non-profit | 37% | 27% | n/a |

Source: College Scorecard

One fix the department has worked on is the loan forgiveness program for borrowers working in public service, which would help educators like Brooks. Prior to the pandemic, even people who were eligible for forgiveness were denied, Kvaal said, which is why fewer than 7,000 people saw forgiveness. Since the Biden Administration announced changes to the program, so far up to 660,000 people have had their loans forgiven through public service.

The Biden administration’s new repayment plan can also significantly cut loan payments or reduce them to $0, Kvaal said, adding that, so far, 4 million people have enrolled in the plan.

Kvaal said the administration is looking at other options.

“The president has asked us to offer loan forgiveness to as many people as possible and as quickly as possible,” Kvaal said. “We’re telling students it’s time for them to repay. At the same time, we’re doing everything we can to reform the student loan program to make sure that students have access to the loan forgiveness that they have earned … and that people are taking advantage of the most affordable payment plan that has ever been created.”

Kvaal said the Education Department is also looking into the amount of debt that comes out of for-profit programs, online graduate programs and the Parent Plus loan program.

Granville, from The Century Foundation, also has national recommendations. For example, Congress should lower the interest rate on student loans. According to The Debt Collective, Congress sets the interest rates for federal student loans. Those rates are tied to the 10-year Treasury note. Because the Federal Reserve has recently been increasing rates, the treasury bond rate has increased and so has the rate for new student loans.

The current fixed rates for new undergraduate loans are at 5.5%, for graduate, 7.05% for professional unsubsidized loans, and 8.05% for Parent Plus and Grad Plus loans.

At the state and local level, Granville said that loan counseling needs to significantly change. Much of the responsibility for understanding student loans is often put on 18- and 19-year-olds, who may be the first in their families to go to college, Granville said.

“The first answer is more grant aid for students so that we can reach a debt-free financing system, not just because it helps students as individuals, but because it helps the state,” he said. “We also haven’t done a great job setting up students for success despite all of their own personal investment in education. We can rectify that situation through more generous repayment plans, but we also need to make sure that we’re giving students high-quality options so they don’t need as much debt in the first place.”

For Brooks, the high school principal with student debt, the ultimate solution is free education.

“If you go to college, you’re stricken with debt,” Brooks said. “If you don’t go to college, then you don’t have a livable wage or enough money to survive. You have to do something.”

And college tuition in California, prior to the mid-1980’s was free, she said.

“I’m of the mindset that education is a public good and it serves everyone to have a highly educated populace,” Brooks said. “It should be free altogether.”