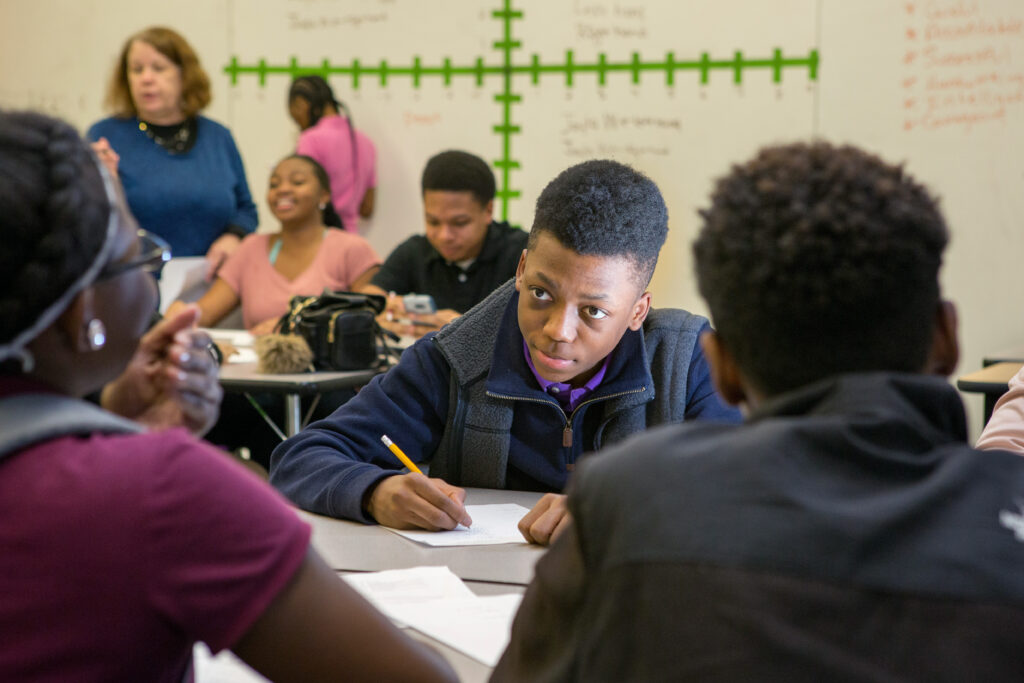

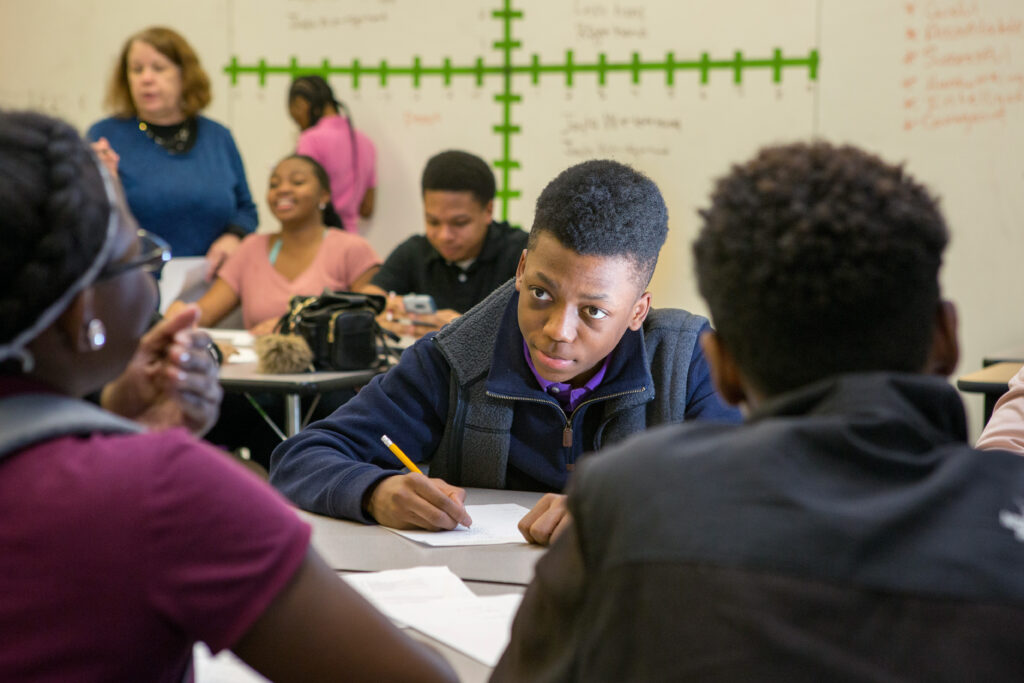

Trump signed an executive order requiring colleges to prove that they are not continuing to practice affirmative action on behalf of racial minorities. He seems obsessed with the idea that Black students are gaining entrance to college without the right test scores. He wants to call a halt to it.

Conservatives believe that admission should be based solely on grades and test scores. They ignore the fact that colleges have other goals they want to meet: students who can play on sports’ teams; who can play in the band or orchestra; who want to study subjects with low enrollments, like advanced physics or Latin. There are also legacy students whose parents went to the college. And students whose parents are big donors, as Jared Kushner’s father Charles was when he pledged $2.5 million to Harvard the year that Jared applied, a story told by Daniel Golden in his book The Price of Admission. RFK Jr. was admitted to Harvard by signing a form with only his name.

Annie Ma and Joycelyn Gecker of the Associated Press reported:

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump on Thursday signed an executive order requiring colleges to submit data to prove they do not consider race in admissions.

In 2023, the Supreme Court ruled against the use of affirmative action in admissions but said colleges may still consider how race has shaped students’ lives if applicants share that information in their admissions essays.

Trump’s Republican administration is accusing colleges of using personal statements and other proxies to consider race, which conservatives view as illegal discrimination.

The role of race in admissions has featured in the administration’s battle against some of the nation’s most elite colleges — viewed by Republicans as liberal hotbeds. For example, the executive order is similar to parts of recent settlement agreements the government negotiated with Brown University and Columbia University, restoring their federal research money. The universities agreed to give the government data on the race, grade point average and standardized test scores of applicants, admitted students and enrolled students. The schools also agreed to an audit by the government and to release admissions statistics to the public.

Conservatives have argued that despite the Supreme Court ruling, colleges have continued to consider race through proxy measures.

The executive order makes the same argument. “The lack of available admissions data from universities — paired with the rampant use of ‘diversity statements’ and other overt and hidden racial proxies — continues to raise concerns about whether race is actually used in admissions decisions in practice,” said a fact sheet shared by the White House ahead of the Thursday signing.

The first year of admissions data after the Supreme Court ruling showed no clear pattern in how colleges’ diversity changed. Results varied dramatically from one campus to the next.

Some schools, such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Amherst College, saw steep drops in the percentage of Black students in their incoming classes. But at other elite, selective schools such as Yale, Princeton and the University of Virginia, the changes were less than a percentage point year to year.

Some colleges have added more essays or personal statements to their admissions process to get a better picture of an applicant’s background, a strategy the Supreme Court invited in its ruling.

“Nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in 2023 for the court’s conservative majority.

It is unclear what practical impact the executive order will have on colleges, which are prohibited by law from collecting information on race as part of admissions, says Jon Fansmith, senior vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education, an association of college presidents.

“Ultimately, will it mean anything? Probably not,” Fansmith said. “But it does continue this rhetoric from the administration that some students are being preferenced in the admission process at the expense of other students.”

Because of the Supreme Court ruling, schools are not allowed to ask the race of students who are applying. Once students enroll, the schools can ask about race, but students must be told they have a right not to answer. In this political climate, many students won’t report their race, Fansmith said. So when schools release data on student demographics, the figures often give only a partial picture of the campus makeup.