A group of education leaders and experts representing both community colleges and four-year universities agreed during EdSource’s Wednesday roundtable discussion that dual admission might be one of the most promising solutions to California’s broken transfer systems.

About 2 million students are enrolled in the state’s 116 community colleges, yet just 10% of them transfer to a four-year university within two years, according to research from the Public Policy Institute of California, or PPIC.

“At the end of the day, it’s really important for us to ensure that transfer is as seamless as possible, that students have the information they need upfront, that it’s actionable, that they’re able to take the courses they need and get through to transfer,” said Hans Johnson, a senior fellow at the PPIC Higher Education Center.

Panelists at the roundtable — “Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?” — agreed that dual admission should be available statewide for all interested students in order to ensure more seamless transfers.

The roundtable included discussion of a state law passed in 2021 that sought to improve transfer rates in California. The postsecondary education trailer bill, or Assembly Bill 132, asked the University of California and required the California State University systems to create such programs for students who didn’t “meet freshman admissions eligibility criteria due to limitations in the high school curriculum offered or personal or financial hardship.”

going deeper

Visit the virtual event page for EdSource’s dual admission roundtable for more information about the speakers and a list of resources.

Dual admission programs offer students guaranteed admission into certain four-year universities after completing a specific list of lower division courses at a community college. This is different from dual enrollment, a process in which students earn college credit while in high school.

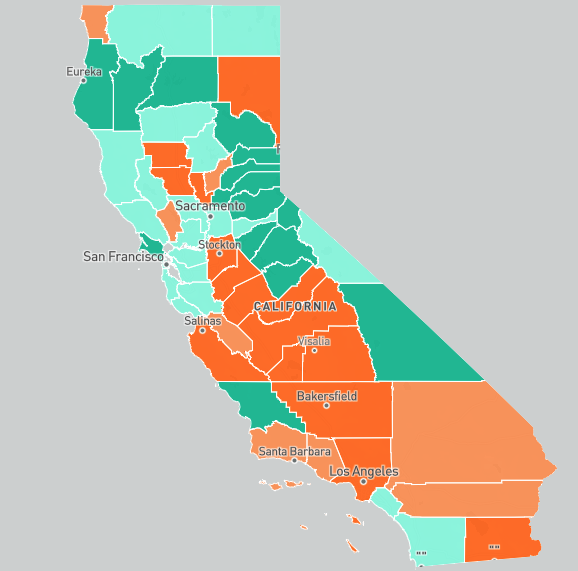

This law could potentially transform the state’s higher education pathways, given that California ranks 41st when it comes to high school graduates who enroll in a four-year university but third in its share who enroll in community college, according to Johnson.

“What that means is that transfer students are critical to ensuring that California really provides a meaningful ladder of educational and economic mobility for our population,” Johnson said.

While the state law calls for a pilot program, CSU’s dual admission program is permanent. It’s called the Transfer Success Pathway Program and launched in fall 2023 with an initial cohort of 2,000 students, said April Grommo, CSU’s assistant vice chancellor of enrollment management.

“We purposely are creating a statewide system,” Grommo said. “We also know that students transfer or take courses at multiple community colleges, and we wanted all of that credit to be reflected in the system and for students to be able to accurately track how many units they’ve completed, what their transferable GPA is, and how they fulfill general education and major prerequisites so that they truly understand the courses that they need to transfer.”

CSU’s program includes all campuses, though some of the most impacted majors are excluded, while UC’s program is limited to six of the nine campuses. CSU also goes beyond what’s required by law by offering dual admission to just about any student who was rejected or simply chose not to attend CSU.

“Just for scale, there’s 162 community college students in the dual admission program for UC, and there’s 2,008 students in the dual admission program for CSU currently in the community colleges,” said panelist John Stanskas, vice chancellor for educational services and support at the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office.

Roundtable panelists also discussed existing programs that could be used as a model for more statewide access to dual admission.

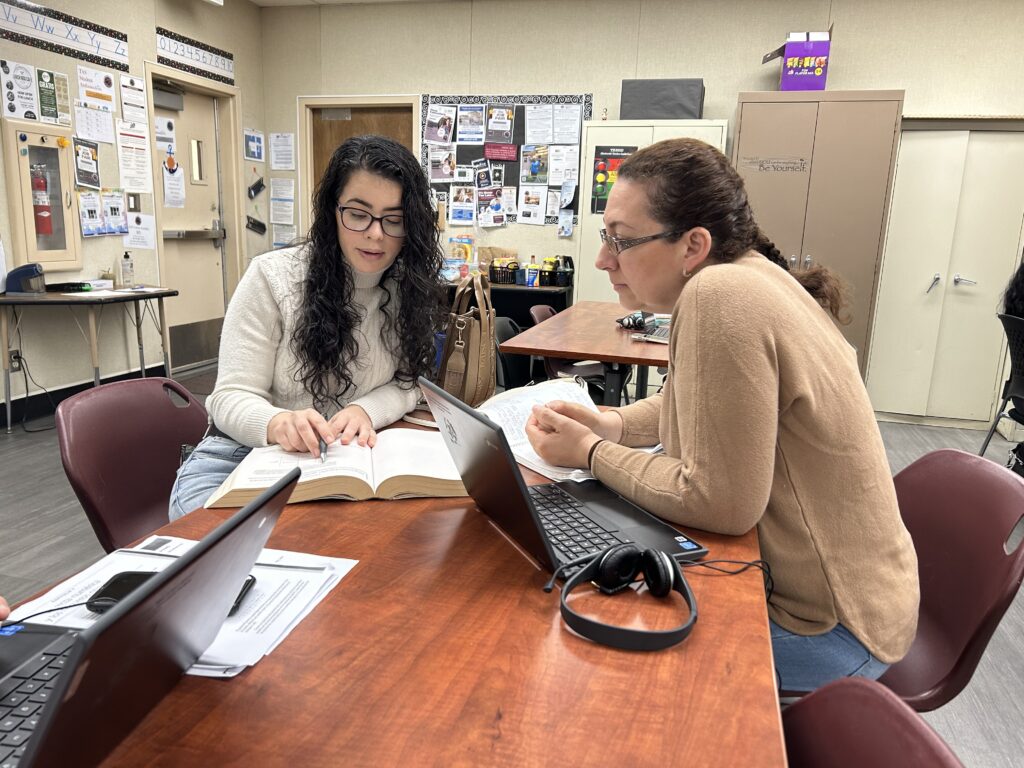

One such example is in the state of Virginia, where Northern Virginia Community College has a dual admission partnership with George Mason University, which sits just 5 miles away. One of the roundtable panelists, Jaden Todd, is a current student at the community college and shared his experience.

A significant benefit of his dual admission program, called ADVANCE, has been the clarity of knowing exactly which classes he’d need to take at his current campus and at George Mason University after transferring. A clear understanding of the courses he’d be required to take was important, he said, as he decided whether to pursue computer science versus computer engineering.

“The fact that I’m able to see not only what classes I need to take here at NOVA (Northern Virginia Community College) but also what it transfers to and what it transfers as, I think that’s one of the biggest benefits of the program,” said Todd, who is on track to transfer to George Mason University in one year.

“I don’t have to worry I’m wasting my money, I don’t have to worry I’m wasting my time. … I don’t have to be a junior taking freshman classes because I didn’t know that this history class was a prereq for this other class.”

Todd said he’s also benefited from having access to a second campus.

“That’s something that I wouldn’t have if this ADVANCE program doesn’t exist because I have access to everything a GMU student has access to because I’m considered a GMU student, even though I’m at NOVA,” Todd said, referring to George Mason University.

Some GMU resources available to Todd are their libraries, a lab with 3D printers, and access to their student clubs.

One of the longstanding challenges that California community college students face when transferring to a CSU or UC is the need to align the courses on their transcripts with the courses they must take after transferring. It’s a challenge that NOVA and GMU avoided by clearly outlining required courses for students enrolled in ADVANCE, but one that students in Long Beach City College’s initial dual admission program often came up against.

In its initial iteration of the program in 2008, Long Beach City College partnered with Long Beach Unified and CSU Long Beach to create the Long Beach College Promise. Understanding which courses students were required to take at each level of their higher education journey, however, “was almost like a maze that they were trying to demystify,” said panelist Nohel C. Corral, executive vice president of student services at Long Beach City College.

In 2019, the college relaunched a revised version called Long Beach College Promise 2.0, Corral said.

“We mapped the courses students would need to take in their first two years here at Long Beach City College and what it would look like in their last two years at California State University Long Beach,” Corral said. “And that required a lot of coordination between the instructional faculty at both Long Beach City College and at Long Beach State, in addition to counselors and advisers in both institutions.”

The relaunched program included 38 students enrolled at Long Beach City College who were also given CSU Long Beach student identification cards with access to the CSU library, sporting events and career services, among other resources. The following year, the cohort included 162 students, which grew to 774 by the fall of 2021.

“We’re still tracking them and collecting data to assess the transfer rates for those cohorts, but for that fall 2019 cohort, we saw significant transfer rates compared to other populations,” he said.

The panelists agreed that geography may become a potential challenge in the development of dual admission programs statewide, given California’s size. They also agreed, however, that regional partnerships become crucial in those areas.

Just last week, for example, Chico State announced a dual admission partnership with seven community colleges. Fresno State and Fresno City College also have a partnership; likewise, CSU Bakersfield has one with Bakersfield College.

Corral suggested “starting off with the data and seeing where the students are transferring to, if you don’t have a local CSU in your direct vicinity, so that you can start those dialogues and start those engagements with those CSUs that your students are going to.”

Stanskas, of the community colleges’ chancellor’s office, said that dual admission can be “especially important for our place-bound students who can’t go a hundred miles or 500 miles to a program. They have family; they have commitments; they have lives that they are unable to move that way.”

Grommo said, “We would love to see every student that’s transitioning from high school and decides that the community college pathway is their pathway that they need to take, really enroll in the Transfer Success Pathway program so we can support them early in their process and help them through this transfer journey.”

This story was updated to accurately reflect Jaden Todd’s name.