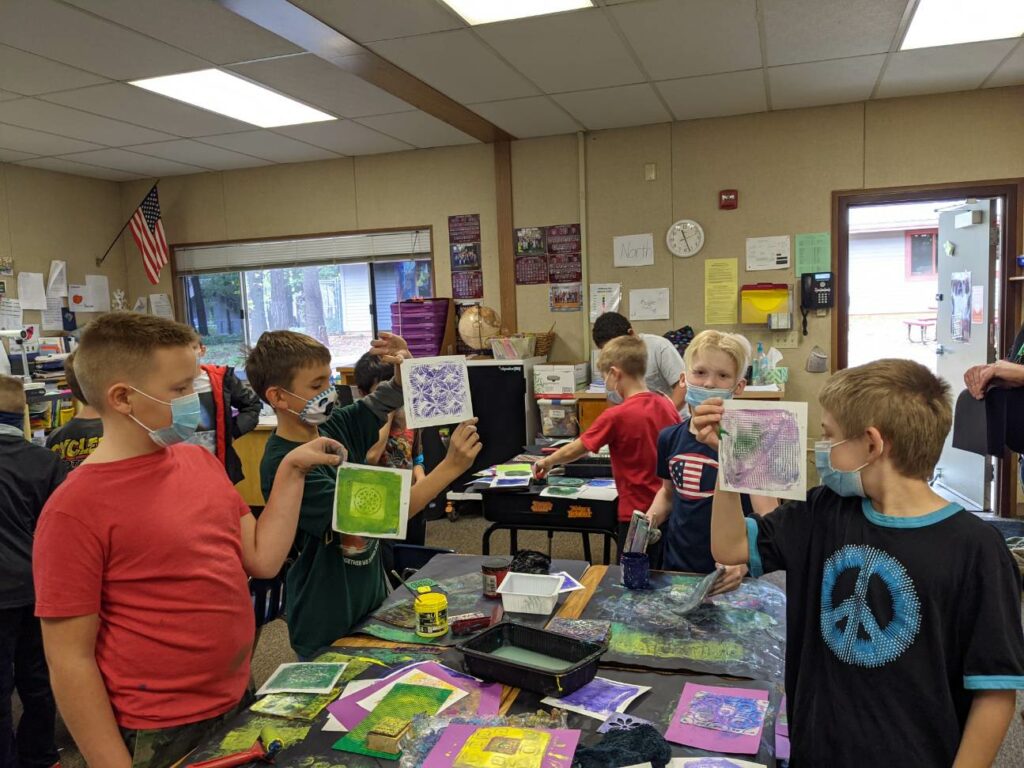

A print-making class at Pine Ridge Elementary.

Credit: Butte County Office of Education

The catastrophic Camp Fire roared through Northern California’s Butte County in 2018, charring the landscape, taking 86 lives and destroying countless homes and habitats in the town of Paradise.

The deadliest wildfire in modern U.S. history at the time, the fire spread at the rate of 80 football fields a minute at its peak, scorching the hearts and minds of the people who live there, especially the children.

That’s why the Butte County Office of Education sent trauma-informed arts educators into the schools, to help students cope with their fear, grief and loss. Buildings can be repaired far more quickly than the volatile emotions of children scarred by tragedy. Long after the flames died down, the heightened sense of fragility that often follows trauma lingered.

upcoming roundtable | march 21

Can arts education help transform California schools?

In an era of chronic absenteeism and dismal test scores, can the arts help bring the joy of learning back to a generation bruised by the pandemic?

Join EdSource for a behind-the-scenes look at how arts education transforms learning in California classrooms as schools begin to implement Prop. 28.

We’ll discuss the aspirations and challenges of this groundbreaking statewide initiative, which sets aside roughly $1 billion a year for arts education in TK-12.

Save your spot

“The people displaced from Paradise were suffering from acute trauma, running for their lives, losing their houses and being displaced,” said Jennifer Spangler, arts education coordinator at Butte County Office of Education. “This county has been at the nexus of a lot of impactful traumas, so it makes sense that we would want to create something that directly addresses it.

Even now, years after the conflagration, many residents are still healing from the aftermath. For example, the county has weathered huge demographic shifts, including spikes in homelessness, in the wake of the fire, which have unsettled the community. All of that came on the heels of the 2017 Oroville dam evacuations and longstanding issues of poverty, drug addiction and unemployment, compounding the sense of trauma.

“Butte County already had the highest adverse childhood experiences (ACES) scores in the state,” said Spangler. “We’re economically depressed, with high numbers of foster kids and unstable family lives and drugs. I think the fire was just another layer, and then Covid was another layer on top of that.”

Chris Murphy is a teaching artist who has worked with children in Paradise public schools as well as those at the Juvenile Hall School. He believes that theater can be a kind of restorative practice, helping students heal from their wounds in a safe space.

“Arts education is so effective in working with students impacted by trauma because the creative process operates on an instinctual level,” said Murphy, an actor best known for voicing the role of Murray in the “Sly Cooper” video game franchise for Sony’s PlayStation. “All arts are basically a way to tell a story and, as human beings, we are hard-wired to engage in storytelling as both participant and observer. A bond of mutual respect and trust develops among the group as they observe each other’s performances and make each other laugh. Over time, the environment takes on a more relaxed and safe quality.”

Another teaching artist, Kathy Naas, specializes in teaching drumming as part of a social-emotional learning curriculum that helps students find redemption in the visceral call-and-response rhythms of the drum circle.

“Trauma is powerful and is connected to something that occurred in the past,” said Naas, a drummer who is currently performing with a samba group as well as a Congolese group based in Chico. “Drumming occurs in the present moment and engages the brain so much that fear, pain and sadness cannot break through.”

To be sure, the use of trauma-informed arts ed techniques goes beyond natural disasters. Many arts advocates believe that these techniques can help children cope with myriad stressors.

“Now more than ever, these cycles of traumatic events, they just keep coming,” said Spangler, who modeled the Butte program after a similar one in Sonoma County in the wake of the devastating 2017 Tubbs Fire.

Children who have experienced trauma may experience negative effects in many aspects of their lives, experts warn. They may struggle socially in school, get lower grades, and be suspended or expelled. They may even become involved in the child welfare and juvenile justice system.

“An individual who has been impacted by trauma, especially ongoing toxic stressors like a home environment with addiction, neglect or abuse, develops a brain chemistry that is detrimental to cognitive function … essentially locking the brain in a fight-flight-freeze cycle,” Murphy said. “With this understanding of what the trauma-affected student is going through, I use theater arts to disrupt the cycle.”

It should also be noted that delayed reactions are par for the course when dealing with post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), experts say. Some children will show their distress readily, while others may try to hide their struggle.

Coming out of the pandemic, the healing power of the arts has been cast into wide relief as public health officials seek tools to grapple with the youth mental health crisis.

“Music can, in a matter of seconds, make me feel better,” said U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy during an arts summit organized by the White House Domestic Policy Council and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). “I’ve prescribed a lot of medicines as a doctor over the years. There are few I’ve seen that have that kind of extraordinary, instantaneous effect.”

Drumming can help build empathy, Naas says, because it allows for self-expression but also encourages a sense of ensemble, listening to others and taking turns.

“Drumming is a powerful activity that creates community,” said Naas. “What I notice about drumming with children is that students become excited, motivated, and fully engaged at the very start. They reach for the rhythms and begin exploring the drums right away.”

Arts and music can nurture a visceral feeling of belonging that can help combat the isolation that often follows a tragic event, experts say. This may also provide some relief for those grappling with the aftershocks of the pandemic.

“The truth is we are all dealing with hardships associated with the pandemic and with learning loss, and we know that the arts, social-emotional learning and engagement can create a healing environment,” said Peggy Burt, a statewide arts education consultant based in Los Angeles. “Children need to heal to develop community, develop a sense of belonging and a sense of readiness so that they can learn.”

The families of Butte county know that in their bones. Trauma can fester long after the emergency has passed, after the headlines and the hoopla. Turning tragedy into art may be one way to heal.

“I’ve seen it over and over in these classrooms, the kids quiet down, they’re calm, they’re focused,” said Spangler. “You can see the profound impact the arts have on the kids every day.”