When Sunny Lee’s son was ready for kindergarten in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic had just begun. His school in Pleasanton, an eastern suburb of the San Francisco Bay, was holding classes online, like most others.

Lee opted out, after seeing what distance learning via Zoom was like for young children.

“I think the formatting was not ideal for young kids. It was just very disruptive and hard to keep track of, and there was just not that much engagement,” Lee said. “Socialization was a big reason for me to send him to school, and he wasn’t getting that.”

The following year, in 2021, when school was back in person, Lee’s son started first grade and her daughter started kindergarten. But after two weeks of school with Covid restrictions, she pulled both children out and began homeschooling them again. They returned to public school for the 2022-23 school year.

Lee’s children are among thousands that did not enroll in public kindergarten in California in 2020 or 2021, years when the state saw drops in kindergarten enrollment. And even among students who enrolled, many missed a lot of days in school.

NATIONAL disengagement from kindergarten

Kindergarten enrollment is down across the country. EdSource collaborated with The Associated Press on a national story about this. You can read that story here.

The pandemic triggered a different attitude about kindergarten, with a growing number of parents either opting for other programs, waiting a year to start kindergarten, or skipping kindergarten and beginning public school in first grade at the mandatory school attendance age of 6 years old.

Some parents were deterred by virtual learning; others were spooked by Covid risks and restrictions. Three years after the pandemic began, many parents still feel their children aren’t ready for kindergarten, after the pandemic disrupted and delayed their ability to play and socialize with others and learn skills from coloring and counting to potty training.

“The pandemic kids have really been struggling on the social side, with ADHD, anxiety and all that comes with not knowing how to play with other children,” said Deana Lundy, client services manager at Bananas, an agency in Oakland that helps families find child care and state subsidies for child care. “If you get a kid that was with grandma all this time and never even went to a child care center, it’s an even bigger barrier.”

Kindergarten is considered a crucial year for setting children up for academic success. Some experts worry that some of the children missing kindergarten will lag behind their peers in elementary school.

Kindergarten enrollment statewide dropped precipitously — 9% — from before the pandemic, 2019-20, to 2020-21, when learning was virtual in most school districts. In 2021-22, the latest year for which data is available, it stayed at relatively the same level as the year before.

Enrollment for 2022-23 was also below projections. The data currently available for 2022-23 lumps together children enrolled in both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten. Transitional kindergarten is a grade before kindergarten, open to some 4-year-olds. Though the overall numbers for both grades together increased by about 5% from 2021-22 to 2022-23, that may be partially due to the expansion of transitional kindergarten to include more 4-year-olds.

The California Department of Education declined to release the 2022-23 enrollment number for transitional kindergarten, adding that the data are set for release in early 2024, on the traditional schedule.

Those numbers are exacerbated by the number of students enrolled but missing a lot of school. According to Hedy Nai-Lin Chang, founder and executive director of Attendance Works, chronic absenteeism — when children miss more than 10% of days in the school year — surged to 40% among kindergarten students in the 2021-22 school year. Among all grades, the rate is 30%.

Chang said part of the reason absenteeism went up so much in kindergarten is that many children did not attend preschool during the pandemic, and because after the pandemic, parents were not allowed to go inside many schools.

“Parents now just drop them off at the door, and they don’t see what’s happening in the classroom. And now they also haven’t had their kids in preschool experiences where they might have understood the value of what you get from early learning,” Chang said.

“The pandemic kids have really been struggling on the social side, with ADHD, anxiety and all that comes with not knowing how to play with other children.”

Deana Lundy, client services manager at Bananas

All income groups opting out

When Sunny Lee and her husband chose to homeschool their children in both 2020-21 and 2021-22, they were concerned about distance learning and the risk of Covid. At the same time, they didn’t want their daughter to have to wear a mask because she has asthma, and they felt it could make breathing more difficult. To make matters worse, wildfire smoke began filling the air in the fall of 2021 and children weren’t getting much outdoor playtime.

On top of all of that, Lee’s husband is a physician and was working long hours during evenings and nights in the ICU during the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Because of school and my husband working in the ICU, the risk was really high, and the schedule was really hard,” Lee said. “They wouldn’t have gotten to spend much time with him.”

Lee contacted a friend in New York who homeschooled her children in New York to get help planning her lessons. Her children returned to school in fall 2022, when her daughter was in first grade and her son was in second grade. She said both her children learned to read at home.

“Looking back, I’m glad I did it,” Lee said. “I think they actually did better. I think they learned more and I was able to focus and hone in on the stuff they needed to learn.”

Some families like Lee’s who are deciding to delay or opt out of kindergarten can afford to pay for another year of child care or preschool or have the time to manage homeschooling.

But the trend to skip kindergarten is also growing among some low-income families who qualify for subsidized child care. Subsidies can be used for many different kinds of settings, including child care centers, home-based family child care programs, and informal care by friends and family.

Christina Engram was all set to send her 5-year-old, Nevaeh, to kindergarten this fall at her neighborhood school in Oakland.

Then she found out the after-school program didn’t have spots for all children and instead, there was a wait list. If Nevaeh didn’t get a spot, she would need to be picked up at 2:30 p.m. most days, and at 1:30 on Wednesdays.

“If I put her in public school, I would have to cut my hours and I basically wouldn’t have a good income for me and my kids,” said Engram, who is the sole parent of two children and works as a preschool teacher in another child care provider’s home day care program. Her younger child is 4 years old.

Rather than potentially cut her work hours or quit, Engram decided to keep Nevaeh in a child care center for another year. She could afford it because she receives a state child care subsidy that helps her pay for full-time child care or preschool until her child is 6 years old and must enroll in first grade.

Engram was not worried about Nevaeh’s ability to do well academically in kindergarten, but she did feel that the girl needed some extra support and attention socially. In part, she said that could be because Nevaeh didn’t have as much interaction with other children during the pandemic, and when she started attending preschool in 2021, all the children wore face masks.

“She knows her numbers, she knows her ABCs, she knows how to spell her name,” Engram said. “But when she feels frustrated that she can’t do something, her frustration overtakes her. She needs extra attention and care. She has some shyness about her when she thinks she’s going to give the wrong answer.”

Socialization is not the only thing some children missed during the pandemic. Some families are also waiting to start public school because their children were not potty-trained during the pandemic, Lundy said. Bananas offers free diapers to low-income families, and staff have noticed the sizes requested getting bigger and bigger since Covid began.

Many reasons for opting out

Overall enrollment in California public schools has been steadily dropping for several years, in part due to a decrease in population and birth rate. But the drop in kindergarten enrollment of almost 40,000 children between 2019-20 and 2020-21 reflects other factors, researchers said.

“Kindergarten, and to a lesser extent first grade, are moving differently from other elementary grades,” said Julien Lafortune, research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. “It’s definitely something that’s not just the underlying demographics.”

The drop in 2020 was likely in large part due to kindergarten being online in most school districts.

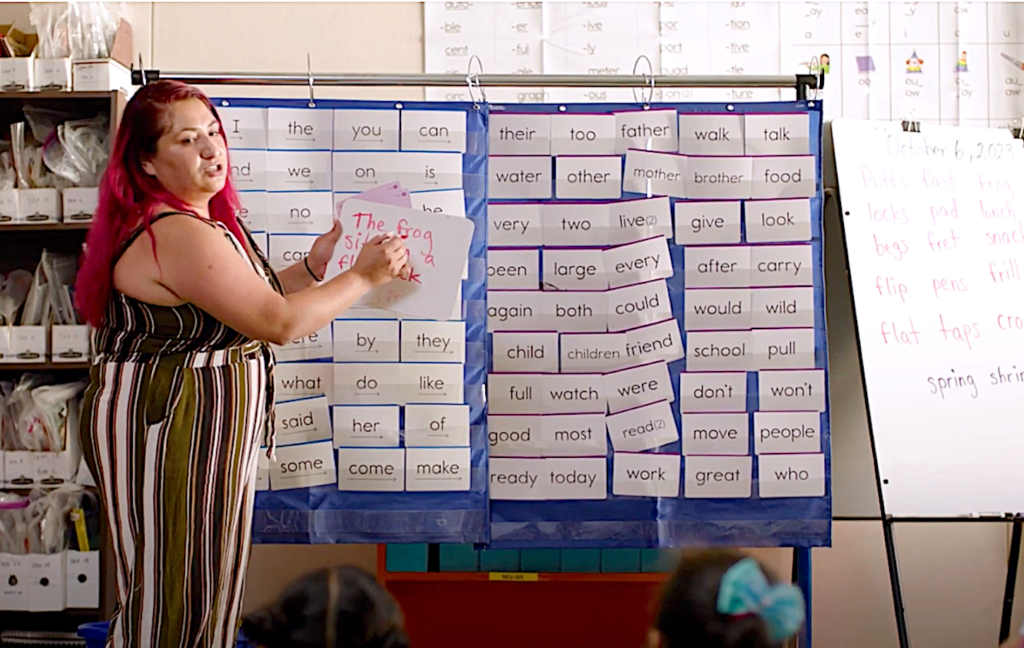

“Asking a 4-year-old to sit in front of a computer for the whole day, it’s totally not what they need,” said Patricia Lozano, director of Early Edge California, a nonprofit organization that advocates for quality early learning. “If you know about child development, you try to avoid screens as much as possible. They need interactions. They need to play.”

When schools returned to in-person learning in 2021, there were many rules for children to follow to prevent the spread of Covid-19: masking, testing and keeping a safe distance from other students.

In addition, some families were concerned about the risk of their children getting Covid-19 in school or bringing it home to younger siblings, particularly before vaccines were available for young children.

Some families may have also moved out of California during the pandemic, in part because of rising housing costs in California coupled with the parents’ ability to work remotely, Lafortune said.

Districts trying to attract youngest students

Several district spokespersons said districts are trying to recruit more children to enroll in both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten, advertising on television, radio, and social media, and holding community events.

Since transitional kindergarten is gradually expanding to serve all 4-year-olds, districts are trying to leverage that expansion to enroll families early.

Their biggest challenge is continuing drops in kindergarten enrollment, reported by more than half of California’s nearly 1,000 districts between 2019-20 and 2021-22.

Districts contacted by EdSource say the decline continued into the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years.

Early learning grades should not be seen as optional in our community. They are essential in the life of young children.

Fresno Unified spokesperson A.J. Kato

Anaheim Elementary School District in Orange County has seen kindergarten enrollment fall year after year since the pandemic. The district’s data for 2023-24 shows a 22.7% drop from pre-pandemic levels, from 2,169 in 2019-20 to 1,676 this year.

The district’s drop in kindergarten enrollment started with Covid-19 and health concerns and expanded, said Mary Grace, assistant superintendent of education services in the district. “Anaheim and most Orange County school districts have experienced ongoing demographic changes and reduced birth rates that play a role in our enrollment numbers over the past few years.”

To stem the drop, Grace said the district is trying to attract more students to both transitional kindergarten and kindergarten with information sessions and an annual “enrollment festival” and advertising that the district offers dual-language immersion classes in Spanish, Korean and Mandarin at all 24 schools in the district, and transitional kindergarten at all schools.

Fresno Unified, which is the third-largest district in the state and also has the third-highest kindergarten enrollment, has seen more than a 16% drop in its kindergarten enrollment from 2019-20 to 2023-24, district data shows.

“The superintendent’s message to our community has been that early learning grades should not be seen as optional in our community. They are essential in the life of young children,” said district spokesperson A.J. Kato. “We are confident that with community outreach efforts and families feeling more comfortable sending their young children to school, we should see and continue increasing enrollment.”

Erica Peterson, the director of education and engagement for School Innovations & Achievement, a national firm that tracks attendance at 356 school districts in California, said school districts need to do more to attract families with young children post-pandemic.

“If we’re trying to stave off declining enrollment, what are we doing to entice people to choose their local home school?” said Peterson. “Because there are a lot of options and the pandemic created a whole wealth of options that didn’t even exist before,” she added, referring to homeschooling and private schools.

Where they went

It’s not completely clear what children did instead of kindergarten in the years since the pandemic. Lafortune said the numbers of students enrolled in private school and registered with the state as being in homeschools are not large enough to account for all of California’s missing kindergartners.

However, since kindergarten is not mandatory in California, parents and guardians are not required to register their children as enrolled in homeschool.

Children enrolled in private preschools or child care centers would not show up in the number of children enrolled in private K-12 schools. Preschools and child care programs are licensed separately by the Department of Social Services and do not have to register with the Department of Education as providing elementary school.

Lafortune said some parents may have chosen to skip kindergarten and then enroll their child in first grade the following year, but first grade has also seen drops in enrollment, so it is difficult to know how many kindergarteners enrolled. He said others may have chosen to wait a year to enroll their children in kindergarten, when they were 6 rather than 5 years old.

Some private preschools opened kindergarten-age classes during the pandemic to cater to families that preferred in-person learning for their 5-year-olds. Even after public schools returned to in-person learning, these preschools continued to attract some families who wanted to keep their children in a more intimate setting with more play and exploration.

Nancy Lopez chose to keep her daughter Naima at a “forest” preschool, Escuelita del Bosque, which holds classes outside in a redwood forest park in the Oakland hills, in part because of the small class size. Kindergarten classes in Oakland can be up to 28 children with one adult. Escuelita del Bosque had a 10-to-1 ratio, with a kindergarten teacher who Lopez says was beloved by families. Naima is now enrolled in first grade at a public school.

“We just felt like there was nothing to lose from Naima being in this environment that’s more catered to this small group,” Lopez said. “It almost felt like we were gifted another year. It was almost pushing off the inevitable.”

EdSource data journalist Daniel J. Willis contributed to this story.