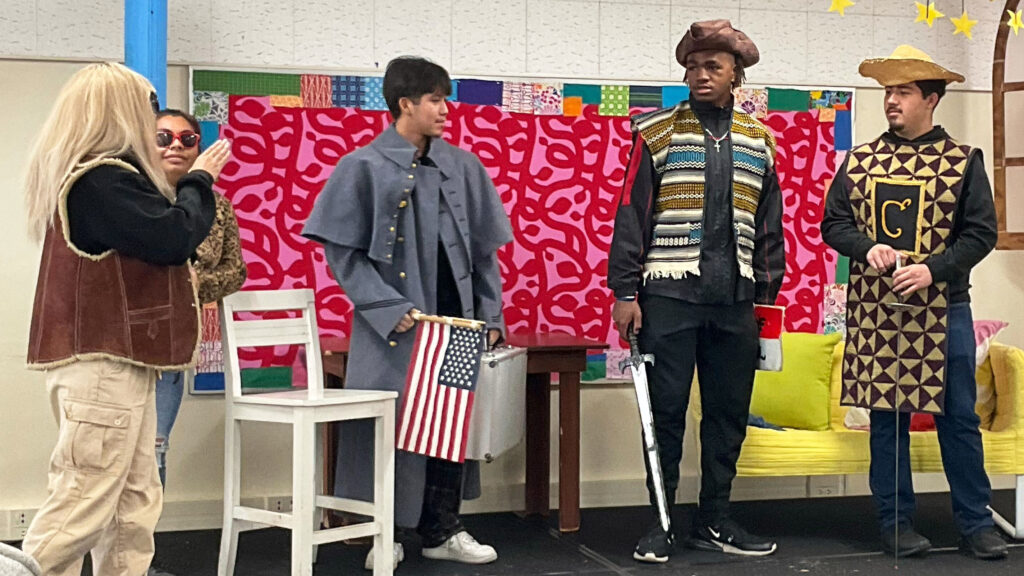

Last school year, Duncan High School students in Gabriel Perez’s ethnic studies class discussed how hip hop and rap music originated from young African American artists highlighting their lived experiences, which were often characterized by social issues such as poverty, gang violence and racism.

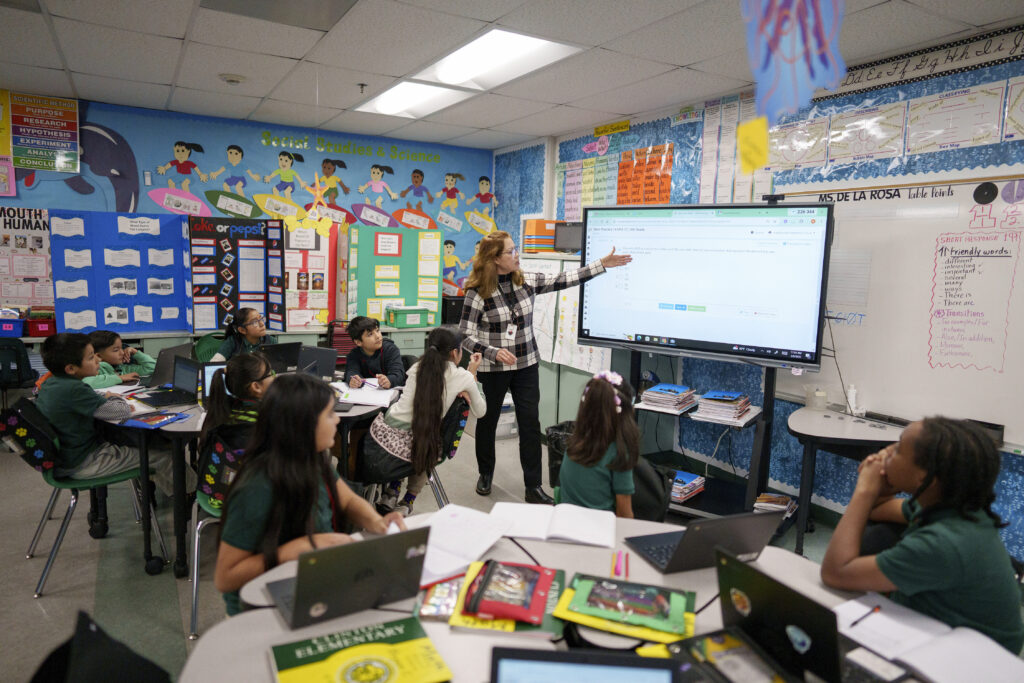

Credit: Lasherica Thornton / EdSource

In October 2017, Fresno Unified teacher Lauren Beal proposed an ethnic studies class at Edison High because she saw “a need for students to learn the historical truth about Black Americans,” an effort supported by the school, which serves higher percentages of Black students than the district, county or state. An ethnic studies class about Latino Americans was also proposed and adopted at the school.

Other teachers across the state’s third-largest district spearheaded such action in their schools.

By 2020, ethnic studies teachers envisioned thousands of Fresno Unified students — not just a few hundred in some schools — having the space to learn the untold stories of diverse communities. They formed the Fresno Ethnic Studies Coalition in hopes of establishing and implementing the course districtwide and increasing the district’s investment.

Following their efforts, in August 2020, the Fresno Unified school board passed a resolution to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement, the Fresno Bee reported at the time. Last school year, 2023-24, ahead of the state’s 2025-26 mandate for an ethnic studies course, Fresno Unified students were required to complete a two-semester course to graduate, according to the Bee.

Despite the enthusiasm that led to the creation of ethnic studies courses and the graduation requirement in Fresno, the development of the program is reportedly at a standstill, leaving some teachers to question whether it’s related to dissension in other parts of the state.

“In a few years, we have come a long way,” said Beal, who is teaching AP African American studies this year.

District leaders consider their decision to create the requirement a bold move because only a few California school systems have mandated ethnic studies classes so far. For instance, some districts have implemented ethnic studies gradually, starting with introductory classes or incorporating concepts of ethnic studies into other courses. Without state funding for implementation, other districts may opt out of the requirement altogether.

In addition to the classes, Fresno Unified has offered its teachers professional development in ethnic studies, providing them opportunities to visit other educators across the state and to obtain graduate certifications in the subject.

Even so, Beal and others accuse the district of being ambivalent in their decision-making, causing the program to stall.

“It’s not that they’ve completely dropped funding and completely dropped support,” Marisa Rodriguez, a Roosevelt High ethnic studies and Chicano studies teacher, said. “There’s no clear rationale and accountability for the decisions being made.”

As a result, although led by educators, the implementation of ethnic studies has not been done with teachers, Fresno Teachers Association President Manuel Bonilla said.

Being supported

Ethnic studies in Fresno Unified

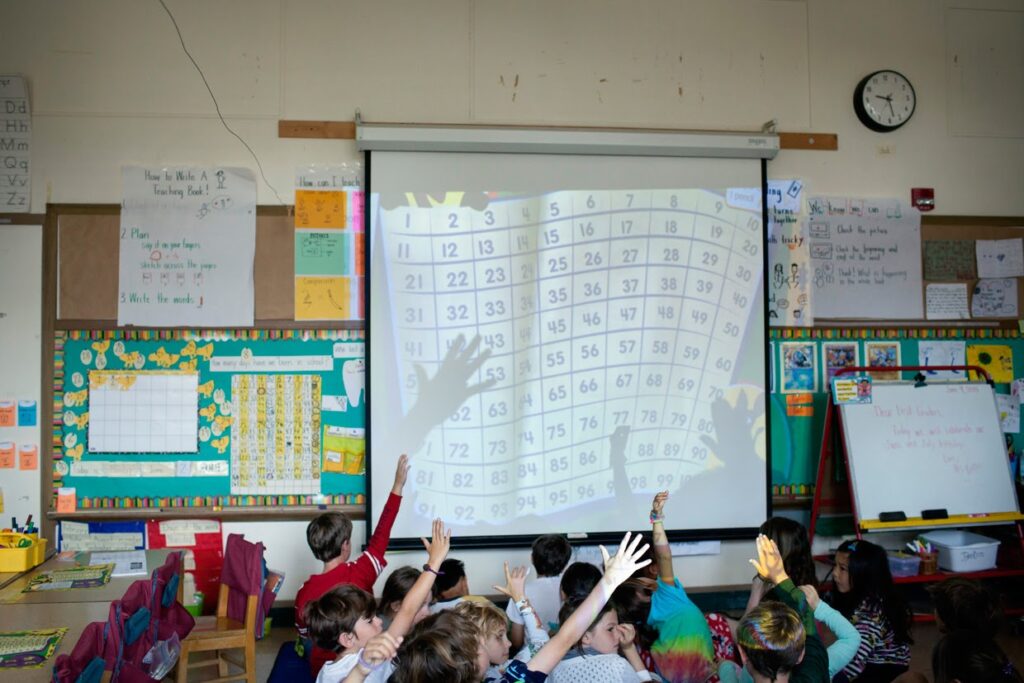

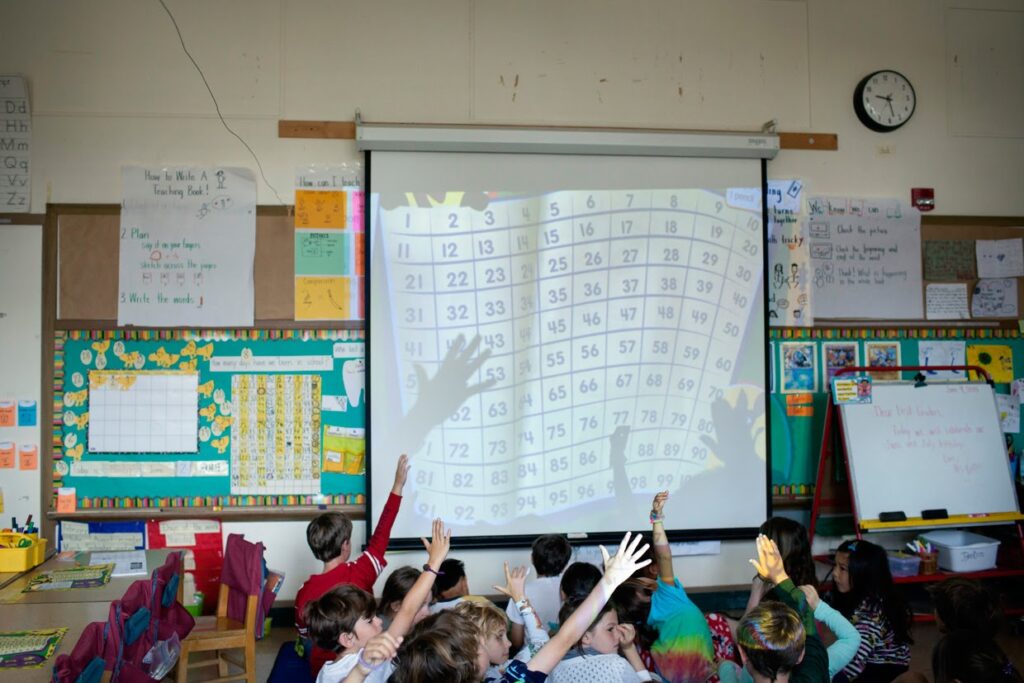

Courses, some of which are offered under dual enrollment, now include comprehensive ethnic studies, Chicano studies, African American studies, Asian American studies, women and gender in ethnic studies and Advanced Placement offerings.

The high school ethnic studies courses meet the A-G graduation requirement to gain admission to the University of California and California State University systems. Middle school courses are an introduction to ethnic studies but do not count toward the A-G or Fresno Unified graduation requirement.

Nine Fresno Unified high schools have at least one ethnic studies course. Ten of the district’s middle schools and Phoenix Secondary, a 7-12 grade community day school, also offer ethnic studies courses.

The success of ethnic studies implementation has depended, in part, on Fresno Unified’s ability to recruit, train and continually support its teachers. Over the years, the number of staff supporting the program has remained the same as the number of teachers and classes has increased.

To this day, nearly five years after the district’s initial action to require the course, ethnic studies has one vice principal on special assignment, Kimberly Lewis, leading and a teacher on special assignment supporting the program of 28 instructors and 1,600 students currently enrolled in courses.

To help support educators, many of whom don’t have a background in ethnic studies, Fresno Unified has developed and offered teachers a chance to learn from each other, but the educators say they desire and need more robust training and “meaningful support.”

Educators with teaching credentials in subjects like history aren’t necessarily experts in ethnic studies, let alone the specific topics that must be covered, said Edison High teacher Heather Miller. For newly offered classes, such as Miller’s Women and Gender in ethnic studies, teachers must gain foundational knowledge of the course and be trained on how to teach ethnic studies and create a curriculum that is relevant, engaging and accessible to high school students, even though much of the existing ethnic studies content has been developed for college.

So, along with district-level support, the district needs experts in the ethnic studies discipline to help in the continual professional development of current and future educators, teachers say. And they want to have input on that.

Having a voice

The termination of professional development without staff or community input continues to cause angst over a year later.

In June 2023, the school board approved an $88,000 contract with San Francisco State professor Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales and her organization, Community Responsive Education, to provide monthly professional development and learning for Fresno Unified instructors. In November 2023, Fresno Unified did not renew the agreement as planned — and still hasn’t, despite it being proposed again last October.

Based on Nov. 1, 2023, board documents, Community Responsive Education would have continued to provide instructional coaching for Fresno Unified middle and high schools offering ethnic studies as part of a three-year partnership. The amended contract to increase services by up to $100,000 was removed by staff from the November 2023 agenda and was not added back in the 2023-24 school year.

According to Rodriguez, teachers learned in November 2023 that the district did not renew its contract with Community Responsive Education, without seeking input on how it would impact teachers or their curriculum development.

Between 2015 and 2017: High school ethnic studies courses in California began gaining momentum as more school districts started offering the class, Education Week reported.

Between 2017 and 2020: Fresno Unified teachers spearheaded the creation of ethnic studies classes, and schools across the district adopted the courses.

May 2020: Ethnic studies instructors, along with students and families, formed the Fresno Ethnic Studies Coalition to advocate for Fresno Unified to establish, fund and staff a districtwide ethnic studies program and implement a graduation requirement.

August 2020: As a result of the teacher-driven efforts, the Fresno Unified school board passed a resolution to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement.

Between the 2020-21 and 2022-23 school years: The district recruited and trained educators interested in teaching ethnic studies and expanded course offerings. The initial plan to require the course for incoming freshmen starting in 2022-23 was delayed in order to recruit teachers.

June 2023: The school board approved an $88,000 contract with the organization Community Responsive Education to provide teacher and curriculum development from July 1, 2023, to June 28, 2024.

Summer 2023: Ethnic studies teachers started meeting with Community Responsive Education consultants to create a framework to guide the teaching method for ethnic studies. The co-developed VALLEY framework — meaning voices, ancestors, liberation, love, empathy and yearning — ensures lessons are relevant for Fresno students. The consulting contract included at least 10 two-hour sessions with teachers and community members.

August 2023: After being delayed by one school year, Fresno Unified started requiring incoming freshmen to take a yearlong ethnic studies course to graduate. The district’s graduation requirement is ahead of the state’s mandate.

Teachers incorporated the VALLEY framework into their classes.

September 2023: Pajaro Valley refused to renew its 2023 contract for the ethnic studies program curriculum of Community Responsive Educaton. Pajaro Valley’s three high schools had been using the curriculum since 2021.

Pajaro Valley Unified had accused San Francisco State University professor Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, the program’s creator, with “unfounded allegations” of being antisemitic, according to The Pajaronian news organization. Tintiangco-Cubales was a part of a 2019 committee selected by the State Board of Education to draft a model curriculum for California. The curriculum was initially rejected amid accusations of political bias and rewritten. Many deemed the curriculum as antisemitic because it did not include the contributions of Jewish Americans as it did for Arab Americans, among other concerns. (Historically, ethnic studies has focused on African, Native, Latino and Asian Americans with the ability to include other racial-ethnic groups or marginalized communities.)

November 2023: The services being offered through Community Responsive Education, which had been underway for nearly five months in Fresno Unified and were being utilized by teachers, needed to be increased. An amended contract to increase those services by up to $100,000, bringing the contract total to $188,000, was presented for board approval.

Former Superintendent Bob Nelson recommended the amended contract for approval at the time.

District staff removed the contract renewal from the school board agenda, essentially terminating the contract and ending services.

In addition to helping create the VALLEY framework that guides the program, the organization was supposed to help develop and align the ethnic studies curriculum to the framework.

November 2023 to September 2024: District leaders, including Instructional Superintendent Marie Williams, said Fresno Unified pulled the contract “out of an abundance of community concern.” She maintained that the district would not say what the specific concerns were.

“We are not in a position to answer that question,” she told EdSource. “Here’s what we are in a position to do: We are in a position to get professional learning (for) the teachers; we’re in a position to contract with other vendors.”

Over time, teachers used professional development they’d received — Community Responsive Education’s monthly 2023 sessions previously offered, other consultant training or district-provided opportunities, such as conferences — to guide their course and curriculum development. Ethnic studies teachers report that they are again “working in silos,” one reason they pushed the district to establish a districtwide program in the first place.

October 2024: On Oct. 9 and Oct. 23, a $100,000 Community Reponsive Education contract was reintroduced for board approval. Again, as in 2023, district staff removed the contract from the agenda before it could be presented or discussed by the board.

Interim Superintendent Misty Her recommended the contract for approval both times.

Up until that point, Fresno Unified’s ethnic studies educators had been meeting with curriculum consultants of Community Responsive Education, including during the summer of 2023, to create the VALLEY framework – voices, ancestors, liberation, love, empathy and yearning – that intentionally centers “local, community, familial and personal experiences,” to guide ethnic studies in the district.

“Out of an abundance of community concern, a decision was made to not move forward with that contract,” said Marie Williams, instructional superintendent for curriculum and professional learning.

The district wouldn’t — and still hasn’t — named the specifics or the source of that concern, despite inquiries by ethnic studies teachers and by EdSource. As part of curriculum development, Community Responsive Education and the district would have garnered feedback from Fresno Unified’s students and community members, according to the scope of the work defined in the contract.

“We asked if it was due to anything in our curriculum,” Beal told EdSource. “How do we know — if you’re not naming the reason the contract was pulled — that we’re fair to teach what we’re teaching and how we’re teaching, and that you’re going to have our backs in the classroom? What is the line that we can’t cross as teachers?”

It left them to speculate why.

Rodriguez said it was because of Community Responsive Education’s association with Liberated Ethnic Studies, an approach to teaching ethnic studies that centers around the liberation of marginalized and oppressed communities by dismantling racism and systems of power.

Ethnic studies educators and activists from across California created Liberated Ethnic Studies and formed the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium after the State Board of Education rejected the 2019 draft curriculum that they had recommended. According to the consortium, the model curriculum that the state board eventually adopted in 2021 removed or redefined critical terms such as capitalism, “fails to depict the true causes of police brutality” and lacks the history of Palestine, among other critiques.

Advocates describe Liberated Ethnic Studies as criticizing and challenging systems of power and oppression, such as white supremacy, imperialism and “settler colonialism,” a system of oppression caused by a settling nation displacing another nation. Critics characterize it as a left-wing ideology focused solely on the oppression of those systems.

There have been conflicts and lawsuits in districts that have worked with the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium. For example, in December, a federal judge rejected a lawsuit against the consortium, a Los Angeles teachers union and educators who created a “liberated” curriculum adopted by at least two dozen school districts. The judge cited a lack of evidence.

Even when curriculums aren’t developed through the organization, a connection to members of the committee that drafted the initial model curriculum and are leaders in the consortium, such as Tintiangco-Cubales, has seemingly led to backlash.

“Where does that leave us if we want to teach anything that is, in any way, connected to Liberated Ethnic Studies?” Rodriguez said.

Lewis, the vice principal on special assignment for ethnic studies, said that the district assured teachers the curriculum was not the concern.

In fact, the district still uses the VALLEY framework that was formed with Community Responsive Education as it was built and co-designed by Fresno Unified educators to be the “foundation” of ethnic studies, Lewis said.

“It is the voices of our teachers,” she said.

Using that VALLEY framework, classes, such as Gabriel Perez’s at Duncan High, discuss the establishment of Fresno’s Chinatown near slaughterhouses and the tens of thousands of people from across California who attended a Ku Klux Klan Fiesta at the Fresno Fairgrounds in the 1920s.

“These were doctors. These were lawyers,” he said. “These were political leaders, a part of this community, who had this racist ideology.”

Rodriguez also incorporates the VALLEY framework into her classes at Roosevelt High. Student reflections on a comic novel about redlining in Fresno revealed their understanding of how race and class can be used to separate people.

The VALLEY framework is an approach to teaching the ethnic studies content, which is currently based on the state’s model curriculum meant to guide districts. In the absence of a consultant to further guide that curriculum and program development, the district has provided opportunities for teachers to attend conferences and learn from other local college professors.

“That doesn’t change our lack of faith or trust in them,” Rodriguez said.

This past semester, the district reintroduced a Community Responsive Education contract, fostering hope among teachers that they’d regain ongoing support through professional learning, curriculum development and coaching from Community Responsive Education.

On Oct. 9 and 23, a $100,000 Community Responsive Education contract was on the agenda for board approval but was removed without discussion — just as it was in 2023. Each time it’s been pulled by staff, it’s been with the understanding, according to some board members, that district leaders will address any concerns.

Eliminating professional development without input or discussion — now three times — impacts educators’ confidence in teaching the course in a thoughtful, authentic way, said Bonilla, the teachers union president.

And it creates a culture of fear among teachers, Beal said.

Feeling protected

Ethnic studies courses and curriculum are not submitted for school board approval. As long as the course and curriculum meet state guidelines, teachers have the autonomy to choose their teaching materials.

But teachers fear that what they teach will be brought under scrutiny. That fear, they say, could impact the district’s ability to recruit or retain ethnic studies teachers.

“Too many times in this district, teachers have been thrown under the bus for teaching material,” Bonilla said.

With ethnic studies content, oftentimes, teachers are tasked with connecting material to something that’s happening in real time, he said.

“We don’t have safety or guidance on how they want us, as teachers, to discuss current events or real-world connections,” Beal said. “It’s a lot of autonomy, but it’s also a lot of fear.”

The district has worked to mitigate such concerns, instructional superintendent Williams said, by building and strengthening administrators’ knowledge and understanding of ethnic studies so that administrators have confidence in the materials teachers present.

“If somebody has a problem with my curriculum, the only way that you can protect me is if you know what it is I’m doing,” said Amy Sepulveda, who has taught Intro to Ethnic Studies at Fort Miller Middle School for four years. “A lot of our leadership don’t know what ethnic studies is.”

When principals and district leaders have a clear understanding of ethnic studies and the curriculum that teachers develop, they can defend and support teachers and their work.

The district has organized monthly meetings “to continue developing curriculum knowledge” among teachers and administrators and arranged for board members to visit ethnic studies classes.

Worry remains.

Lewis, the vice principal on special assignment, attributes some worry to the idea of ethnic studies. A key concept of ethnic studies is to teach the counter narrative, stories and perspectives never documented or left untold in other classes, many advocates and educators say.

“I think everyone is struggling with how we work and shift mental models in a system that has been boxed in K-12 education.” Lewis said. “How do we unlearn and shift mental models on teaching the counter narrative?”

Lewis realizes that teachers want protection of the materials that they use, including those presenting counter narratives.

But there is none, she said. There’s not a policy or practice.

Without that protection, can ethnic studies thrive?

“We keep on moving forward without assuring the safe and sacred protection of the teachers, students and community that ethnic studies is supposed to uplift,” Sepulveda has said about ethnic studies implementation thus far.

To Williams, the way to assure staff of that safety and support is a consistent and continued commitment to move forward.

“We recognize that we are in this moment where there is concern and consternation,” she said. “To keep leaning in and to keep listening, to keep being responsive — I think that’s how you reassure them. I think it’s your actions.”