Oakland students rally for lead-free drinking water in their schools in front of city hall Monday, Sept. 30, 2024.

Monica Velez

Este artículo está disponible en Español. Léelo en español.

Oakland student Hannah Lau said she only discovered there were elevated lead levels in her school’s drinking water this year through her teacher. There wasn’t an announcement from the principal, nor was there an assembly to notify students.

“I was really shocked and scared,” the 13-year-old said. “How long have we been drinking this water? Is it really bad? Is it in my body? How poisoned am I?”

The Oakland Unified School District is one of the few districts in California that has continued to test lead levels in drinking water years after it was no longer required by state law. In 2017, an extension to the existing law (AB-746), also known as the California Safe Drinking Water Act, required districts to sample water from at least five faucets in every school and report the findings to the state by July 1, 2019. State funding for lead testing ended after the deadline.

The law resulted in school districts getting a snapshot of lead contamination in their drinking water at that time. But because of the one-time requirement that districts test only a small sample of faucets, and exemptions for charter and private schools, there are no statewide records that offer an accurate representation of lead presence in California schools currently.

Seven years after the law went into effect, school districts and communities, including Oakland, are still grappling with how to keep lead out of drinking water.

“We know there’s lead in the plumbing, and even if it is a low value (of lead concentration), we know it’s persistent,” said Elin Betanzo, a national drinking water expert and founder of Safe Water Engineering. “If a kid is drinking water every day at school, that lead is always there. That lead can get into any glass. The studies show that the low-level exposures have a disproportionately high impact on the brain.”

An EdSource analysis of school district data of lead concentrations in Oakland Unified water in 2019 and 2024 shows many inconsistencies. In some cases, the same water fixtures that were tested both years yielded completely different results, with lead concentrations below the state’s threshold of 15 parts per billion (ppb) in 2019, and in 2024, some fixtures reached triple digits.

“We know that this happens,” Betanzo said. “We have extensive records of data that if you sample the same tap at a school you can get a low value that would appear safe one day and could get an extremely high, concerning level the next day.”

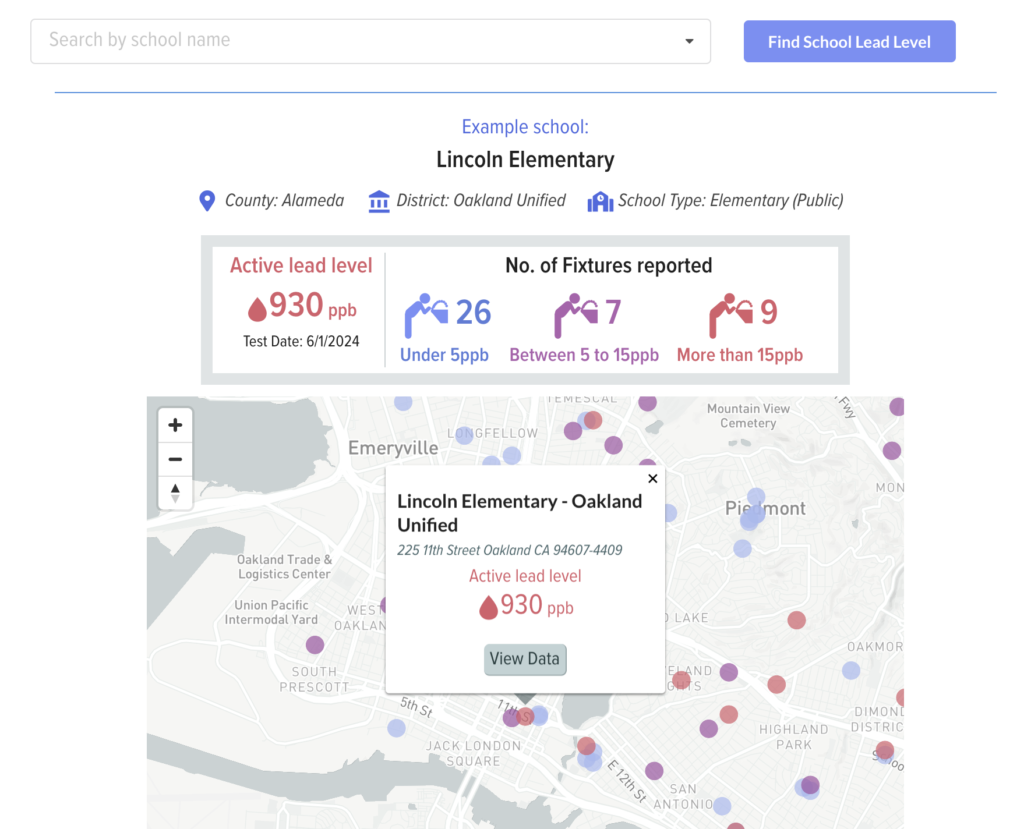

Lincoln Elementary School, between downtown Oakland and Lake Merritt, had some of the highest levels of lead in Oakland Unified after the district tested there earlier this year.

A drinking fountain at Lincoln with the highest lead concentration tested at 930 ppb in June. That same fountain was tested in 2019 at 2.1 ppb, which is under the state and district threshold for safe water. The Safe Drinking Water Act only required faucets that tested above 15 ppb to be fixed. However, Oakland Unified adopted a stricter policy in 2018 that says if levels are higher than 5 ppb, the issue requires remediation.

California’s lead action level was set at 15 ppb following the recommendation of the Environmental Protection Agency’s lead and copper rule. On Oct. 8, less than a month before the Nov. 5 election, that limit was lowered to 10 ppb by the Biden administration to ensure that drinking water is safe throughout the country. Some states, but not California, had already adopted lower limits prior to the change.

Without the district’s follow-up testing in 2024, Oakland Unified officials wouldn’t have discovered the faucet that was once deemed safe is dangerous. It’s not an isolated incident. Another drinking fountain at Lincoln tested 3.3 ppb in 2019 and in June tested at 410 ppb.

“This happened in my children’s elementary school,” Betanzo said. “So it does happen. It is normal. We know all about it. And yet the requirements that states have put together for school drinking water don’t acknowledge the science of this.”

The release of lead in water is sporadic, and testing results from the same fixtures are often inconsistent, Betanzo said.

“Schools have been doing these one-time samples, and if they get a low sample (value), they say, ‘Hey, the water is safe,’” Betanzo said. “And that’s not true. We have lead throughout our plumbing,” referring to school districts in general.

In schools, water doesn’t run for long periods on weekends and during breaks, Betanzo said, and it doesn’t allow the corrosion control that is more common in houses. There needs to be a constant turnover of water for corrosion control to work, she said.

Faucets with elevated lead levels have been taken out of service, according to Oakland Unified spokesperson John Sasaki. Often, the faucets are fixed by replacing filters and are retested before they are back in service.

“With regard to inconsistencies between lead levels found in 2019 … and now, our estimation is that because most of our schools are relatively old, and the features including the plumbing are old, there has been degradation of some aspects of the systems since 2018, which has led to the elevated levels we have recently found,” Sasaki said in an emailed statement.

The inconsistencies in lead samplings aren’t unique to Lincoln. Similar examples occurred in Edna Brewer Middle School, Cleveland Elementary, Crocker Highlands Elementary, Horace Mann Elementary, Bella Vista Elementary, and Fruitvale Elementary. The lead levels recorded in 2019 were all either under 5 ppb or 15 ppb at all of these schools and higher in 2024.

“It’s terrifying at a personal level,” Oakland parent Nate Landry said. “It’s terrifying at a collective level.”

Failures of the Safe Drinking Water Act

The state’s drinking water law didn’t require districts to do follow-up testing, which is part of the reason schools that haven’t tested lead levels since 2019 have no way of knowing if students and staff are still being exposed to elevated lead levels in drinking water.

The law exempted thousands of private and charter schools on private property from testing for lead levels. Not every faucet or drinking fountain was required to be tested. And schools that were built after 2010 were also not required to test lead levels.

California has more than 10,000 public schools, including about 1,300 charters, and it’s possible thousands of fixtures have yet to be tested for lead.

State law required faucets — not valves — to be changed in fountains with lead levels exceeding 15 ppb, said Kurt Souza, an enforcement coordinator for the division of drinking water at the State Water Resources Control Board, which could be why lead levels were inconsistent between 2019 and 2024. Valves are used to control the water flow and are usually placed under the sink.

“Never change out an old faucet without changing the valves,” Souza advised.

Critics of the state drinking water act have said the 15 ppb limit for lead in drinking water was too lenient. Some school districts, including Oakland, have set lower limits.

According to the EPA’s website, “There is no safe level of lead exposure. In drinking water, the primary source of lead is from pipes, which can present a risk to the health of children and adults.”

The EPA has also said the 15 ppb level is not a measure of public health protection, Betanzo said.

“15 ppb was selected as an engineering metric,” said Betanzo, who formerly worked at the EPA. “It is an indicator of corrosion control effectiveness. So, if a water system looks at the 90th percentile of its sampling results, and it’s greater than 15 parts per billion, it tells them they have an out-of-control corrosion situation that needs to be addressed.”

Other districts that have tested for lead levels after 2019 include San Francisco Unified, San Diego Unified, Laguna Beach Unified, Castro Valley Unified, Encinitas Union Elementary, La Mesa Spring-Valley, and San Bruno Park Elementary.

“Did you find every spot that has a high lead? Probably not,” said Souza. “Some schools probably had a hundred faucets and then we only sampled five of them. I thought it was a really good start, and it showed some schools had problems, which then did more samples and, and did more things to it.”

There’s currently no directive under the state or the federal Environmental Protection Agency to test lead levels in school drinking water, said Wes Stieringer-Sisneros, a senior environmental scientist for the drinking water division at the State Water Resource Control Board.

Since the state requirements for lead testing ended, there have been efforts to pass state legislation that would have required follow-up testing, AB-249, but Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill in 2023. The following year, another bill, AB 1851, which would have created a pilot testing program, was introduced but held in the Senate Appropriations Committee.

“It was another blow,” said Colleen Corrigan, health policy associate for Children Now, a statewide research and advocacy organization that co-sponsored both bills. “We hope that Proposition 2 will pass, and we really want to make sure that that distribution of money is equitable and accessible.”

Voters passed Proposition 2 on Nov. 5, and that will provide, among other things school-related, up to $115 million to remove lead from drinking water in schools.

How Oakland is getting the lead out

Although Oakland district officials have made progress in repairing faucets since the most recent testing results in the spring, some people have lost trust and confidence in the district.

Shock waves burst through the Oakland community at the start of the school year when educators, parents, and students discovered the district was withholding testing results that showed elevated levels of lead in water in dozens of schools. Some lead testing results were available in April and families didn’t start to receive notices until August.

“The scope of their (Oakland Unified) failure to communicate pretty crucial public health information was shocking,” parent Landry said.

District officials did acknowledge they did not properly communicate with families about elevated lead levels.

During a rally in front of Oakland City Hall last month, parents, students, educators and community organizers urged the school board and City Council to do more to get the lead out of school drinking water, even though the district is already doing more than most.

The Get the Lead Out of OUSD coalition, which includes the Oakland teachers union and other community partners, has a list of demands, the first being instating a new, highly ambitious threshold of lead levels of zero parts per billion. Other demands include testing all water sources at Oakland schools immediately and annually, testing all playgrounds, gardens and outdoor areas, facilitating free blood testing for students, teachers and community members, and completing infrastructure repairs.

District officials also said they will continue to do more lead testing through the end of the year and promise more transparency.

“We have instituted improved protocols to ensure we are more transparent and more consistent in our communication with our families and staff,” a statement said. “We will inform you before any testing begins at your school.”

A priority has been to install more FloWater machines, which are filtered refillable water stations, the statement said. Most schools have at least two, and 60 additional machines were installed this school year. The district plans to install 88 more.

Lau said she and her classmates were given reusable water bottles and told to only drink from purification water stations or bottled water. If a student forgets to bring a water bottle to school, there are extras, but not always, she said. The last resort is asking a friend for a drink from their water bottle or purchasing bottled water.

“Please fix this issue,” Lau said. “I don’t want to be drinking lead. I don’t want lead anywhere near me. I want to be safe; I want to grow up safe.”

)

)