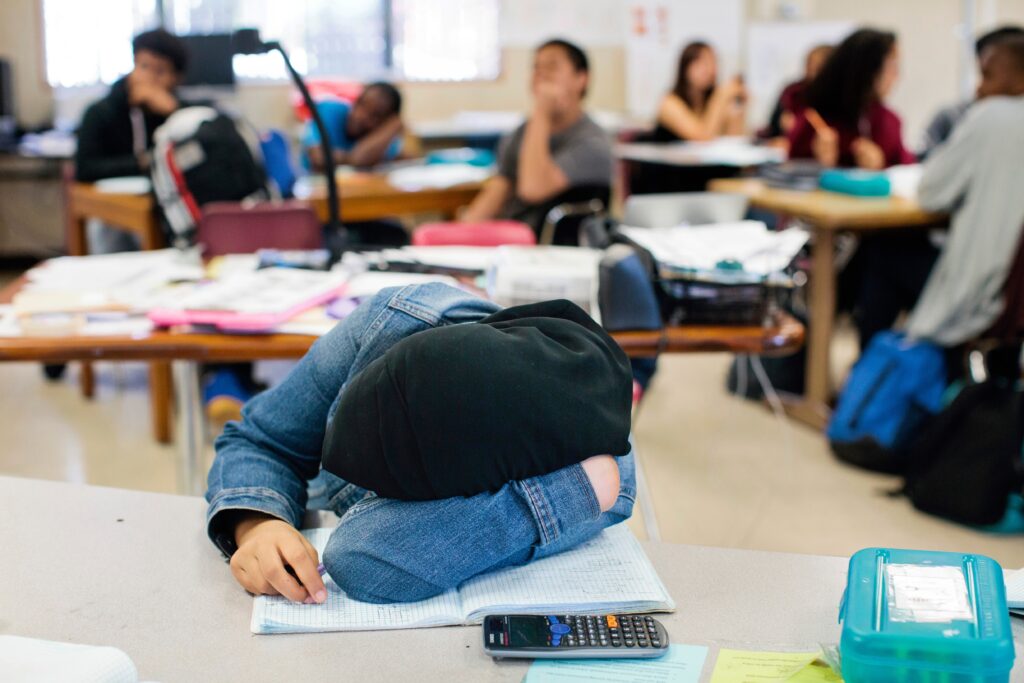

Students move into UC Berkeley’s Anchor House on Aug. 21, 2024.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

Elizabeth Diaz was the valedictorian of her high school class in Bakersfield. But that does not mean her path to a four-year university has been easy.

“Honestly, (UC Berkeley has) been my dream university since I was in high school,” Diaz said. “I had originally committed before, but unfortunately I wasn’t able to afford it.”

Instead, Diaz spent two years at Bakersfield College, where she “felt a lot of stigma” for not having gone further from home for the next step in her education. “I felt like, you know what, I’m here. I’m not going to be able to make it anymore. I’m just going to stay here in my city,” Diaz said.

While attending community college, she pushed herself to get involved during the first two years, knowing it would take more to prepare herself for another shot at UC Berkeley than simply attending classes. “I started off getting involved with on-campus jobs as a tutor,” Diaz said. “I got involved with student government. I was a student activities manager, I created the history club on campus trying to, you know, get rid of that sense that ‘history sucks,’ because history is so cool. We’re living in it all the time.”

Diaz also got involved in the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA) because the organization is “tied … with my identity growing up as a daughter of an undocumented family … (I’m glad about) getting involved with the nonprofit CHRILA (and) advocating for other families who are still struggling,” Diaz said, adding, “Thankfully my family has been transitioning; my dad actually now has citizenship.”

And she also took advantage of resources like Bakersfield College’s Extended Opportunity Programs and Services.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LMUVNQMsZY

“I kept myself accountable. Being a part of resource programs like EOPS … and the TRIO Student Support Services made me really, really, really super grateful for my community college, for allowing me the opportunity to get to know myself better and what I wanted to do.”

Last month, Diaz finally achieved that dream, enrolling in UC Berkeley as a transfer student and moving into Anchor House, a brand-new residence hall specifically for transfer students on the university’s campus.

Anchor House, a gift from the Helen Diller Foundation, is an apartment-style community that features high-end amenities such as a yoga studio, a rooftop vegetable garden and multiple lounge areas. It is also home to the new Transfer Student Center.

“It’s like walking into a nice hotel,” a parent marveled when passing through the entrance.

Immediately upon entering, the extravagance of the modern fixtures screamed resort more than undergraduate student housing. Even with ceilings akin to a cathedral, the front desk emitted an approachable warmth with the eager smiles of the resident assistants — a far cry from many freshman dorm buildings at UC Berkeley that don’t even have a lobby.

Anchor House’s transfer-exclusive status brings both security in housing and an opportunity to grow relationships.

“Last year coming in, I was still waiting on on-campus housing until the last round of housing offers, which was three weeks until the school semester started. It was nerve-wracking not having a place to live as the semester was approaching,” said Max Ortega, a transfer student from Los Medanos College in Pittsburg, now entering his senior year.

Without a well-established transfer community, the transition to UC Berkeley was difficult last year as a new student, said Jonathan Zakharov, a rising senior from Diablo Valley College in Pleasant Hill. He noted the stark contrast between new first-year students “right out of high school,” and transfers with life experience and diverse backgrounds, saying it was “impossible” to find other transfer students to connect with after moving in.

“If this were my first year while living at Anchor House, it would have been easier to relate to people,” Zakharov added.

While transfer students make up 21% of undergraduates at UC Berkeley, the lack of community was clear. According to Anchor House resident director Ryan Felber, transfer students can feel “impostor syndrome,” which he hopes to remedy through a “built-in” community in students’ residential lives.

“This space will be a literal anchor for them to hold onto and a place to call home,” Felber said.

Anchor House is open to both newly admitted and current transfers — and for Jennifer Dodson, a re-entry student who spent 20 years working in corporate accounting, living at Anchor House in her final year will be a major shift from last year’s housing.

“As a junior transfer, I was placed in Unit 1 Putnam, which is primarily a freshman dorm,” Dodson said. “I was also roommates with a freshman student, but she was mature, and we got along very well.”

Dodson, who turned 40 in June, is looking forward to Anchor House’s “networking opportunities,” an aspect she wasn’t able to experience in her first year living in Unit 1, in addition to building new friendships and meeting new people from diverse backgrounds.

“It’s never too late to go back to school,” said incoming junior transfer and re-entry student Amye Elbert, who raised three children and one grandchild up until starting at UC Berkeley this fall.

Elbert recently turned 52 years old, and is a first-generation college student.

“Growing up, I always wanted to have a college degree, but in my aversive background, no one talked about college,” Elbert said. “I had kids early and had to take jobs I wasn’t interested in. Once my kids grew up and I didn’t have four mouths to feed, I knew I wanted to fulfill my dream of going to school.”

After spending three years at Los Medanos College and earning three associate degrees in fine arts, art practice and art history, she will major in art practice at UC Berkeley with the aim of becoming a middle school art educator.

“When I was in middle school, I just entered foster care and felt awful. But I had this art teacher who made me feel important and loved my artwork, and I want to do something similar for young students in situations like mine.”

Jo Moon is a third-year political economy and media studies student at UC Berkeley and a member of EdSource’s California Student Journalism Corps.