In data science classes, students write computer programs to help analyze large sets of data.

Credit: Alison Yin/EdSource

The article was updated March 5 to include the letter from high-tech executives supporting the Algebra II requirement. It also clarifies that AP Statistics is for students who have completed Algebra II.

An influential committee of the UC Academic Senate weighed in again last month on the contentious issue of how much math high school students must take to qualify to attend a four-year California state university.

It ruled that high school students taking an introductory data science course or AP Statistics cannot substitute it for Algebra II for admission to the University of California and California State University, starting in the fall of 2025.

The Board of Admissions and Relations with Schools or BOARS reaffirmed its position by accepting the recommendations of a workgroup of math and statistics professors who examined the issue. That workgroup determined that none of these courses labeled as data science “even come close” to qualifying as a more advanced algebra course.

Robert Gould, a teaching professor and vice chair of undergraduate studies in the statistics department at UCLA and lead author of Introduction to Data Science, said that he disagrees with BOARS’ decision. The course was created under the auspices of the National Science Foundation through a math and science partnership grant.

“We are disappointed, of course,” he said. “We believe our course is rigorous and challenging and, most importantly, contains knowledge and skills that all students need for both career and academic success.”

But how, then, will UC and CSU ultimately fit popular data science courses like CourseKata, Introduction to Data Science, and YouCubed’s Explorations in Data Science into course requirements for admission? That bigger question won’t be determined until May when the math workgroup will issue its next report.

Data science advocates are worried that BOARS, which commissioned the review, may disqualify data science and possibly statistics under the category of math courses meeting the criteria for admissions. Increasing numbers of high school students are turning to introductory data courses in a world shaped by artificial intelligence and other data-driven opportunities and careers. They see them as approachable alternatives to trigonometry, pre-calculus and other rigorous courses students must take to major in science, technology engineering or math (STEM) in college.

Dozens of high school math teachers and administrators have signed a letter being circulated that will go to the UC regents. It reiterates support for data science and statistics courses and criticizes BOARS for not consulting high school teachers and data science experts for their perspectives.

“Our schools and districts have adopted such courses because they provide an innovative 21st-century experience that excites and engages students, impart tangible quantitative skills needed for a wide variety of today’s careers and academic fields, and offer new ways for students to interact with and learn mathematics,” the letter states.

Pamela Burdman, executive director of the nonprofit Just Equations, agreed in a blog post titled “The Latest in the Inexplicable War on High School Data Science Courses.” “The bottom line is that districts are increasingly offering these courses because they are relevant and engaging for many students who otherwise would be turned off by mathematics,” she wrote.

Will it help or hinder equity?

Critics of substituting introductory data sciences courses for advanced algebra include STEM professors at UC and CSU. Many say they support data science, but not courses lacking the full range of math topics in high schools that students need for STEM or any major requiring quantitative skills. Skipping foundational math in high school will set back the cause of equity for underserved students of color, not advance it, they argue, by creating the illusion that students are ready for statistics, computer science and data science majors when they aren’t. That may force them to take catch-up courses in community college.

“The only way we’re going to diversify STEM fields is to keep historically excluded young students on the algebraic thinking pathway just a little bit longer,” Elizabeth Statmore, a math teacher at Lowell High in San Francisco and former software executive, wrote to EdSource last year. “That will give them the mathematical competencies they will need to make their own decisions about whether or not they want to pursue rigorous quantitative majors and careers.”

Proponents of holding the line on Algebra II and encouraging more students to pursue STEM majors are circulating their own attention-grabbing letter titled Strong Math Foundations are Important for AI. The signers, including Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, his nemesis Elon Musk, founder of Tesla, SpaceX and CEO of X, and executives from Apple, NVIDIA, Microsoft and Google, “applaud” UC for maintaining the math requirements.

“While today’s advances might suggest classic mathematical topics like calculus or algebra are outdated, nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, modern AI systems are rooted in mathematics, making a strong command over math necessary for careers in this field,” it reads. “Failure to maintain standards in the mathematical curriculum in public education will increase the gap between public schools — especially those of under-resourced districts — and private schools, hampering efforts to diversify STEM.”

Surprise actions by UC Office of President

For decades, UC and CSU have required that students complete three years of math with at least a “C” — usually in the sequence Algebra I, Geometry, and Algebra II, also called Advanced Algebra – as the math component of A-G, the 15 courses needed for admission. For students taking integrated math, it is Math I, II and III. Both university systems recommend a fourth year of math, and most students take at least that; aspiring STEM majors take two or more additional courses leading to Calculus.

BOARS establishes policies on admissions, but a small office in the UC President’s Office, the High School Articulation Unit, vets tens of thousands of courses that developers and high school teachers submit for approval. Starting in 2014, the unit began authorizing AP statistics and new data science courses as “validating” or satisfying Algebra II or Integrated Math III content requirements. That meant they either built on the content standards that students had covered or would cover in the course.

Although AP Statistics doesn’t cover most Algebra II topics, the rationale for validating it and data science courses — mistakenly so, BOARS determined in retrospect — was that Algebra II includes some statistics, and most teachers never get around to teaching it. That was problematic for introductory data science courses, because the state hasn’t set standards for what should be covered in the courses. The College Board, the creator of AP Statistics, states that the course is designed for students who have completed Algebra II.

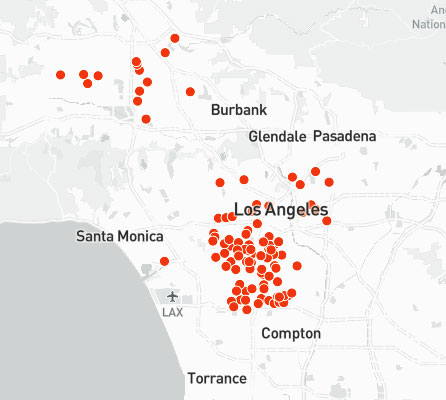

During the last few years, the staff in the review office approved the three most popular data science courses in more than 400 high schools. After analyzing the three courses, the UC workgroup professors concluded, “We find these current courses labeled as ‘data science’ are more akin to data literacy courses.”

UC academic committee meetings, including BOARS, are closed to the public. But minutes from the July 2023 meeting indicated that some faculty members were dismayed that the articulation office had validated so many data science courses without their knowledge. “At least one member repeatedly suggested that UCOP has misinterpreted/misapplied the advanced math standard for years — and absent correction, will continue to do so — and so review of all current courses potentially implicated is needed,” the minutes state.

BOARS hasn’t ruled out approving future data science courses that include more advanced algebra as a substitute for Algebra II; the articulation office has validated Financial Algebra for that purpose. BOARS invited course alternatives in a June 2020 statement, saying it saw the expanded options “as both a college preparation and equity issue.”

But data science proponents are concerned that the math workgroup will take the opposite position and recommend that the three introductory data science courses be treated as elective courses for A-G but not fourth-year math courses. Ruling that way, they argue, would discourage future non-STEM majors from taking an alternative quantitative reasoning course as seniors. Such a position would reinforce a narrow view that only courses leading to Calculus are legitimate math offerings in the senior year.

“Revocation of Area C (math) status will significantly reduce our ability to foster students’ statistical and data competency or incentivize enrollment in these programs, at a time when such quantitative abilities are increasingly necessary for functioning personally and professionally in the 21st Century,” the letter to the UC regents says.

Lai Bui, a veteran math teacher at Mills High School in the San Mateo Union High School District, said there’s no justification for treating CourseKata, an introduction to data science course, differently from AP Statistics, which BOARS has qualified as a fourth-year math course. Students in CourseKata use coding to analyze datasets, while AP Stats students use graphing calculators, which have limitations, she said.

UCLA and CSU Los Angeles created CourseKata in 2017 as a semester course for college and as a two-semester course for high schools; otherwise, they are similar, said Bui, who has taught it for four years.

“CourseKata is definitely not data literacy,” she said. “It’s a math course, like AP Statistics, only more real-world connected. I see students succeeding in math instead of thinking, ‘I am not a math person.’”

In 2023, the CSU Academic Senate expressed frustration that UC was approving courses in data science in lieu of Algebra II without consulting it and urged more joint decision-making involving A-G decisions. In January, three CSU professors were added to the 10-member UC math workgroup.

Mark Van Selst, a psychology professor at San Jose State and member of the Academic Preparation and Education Programs Committee, considered CSU’s counterpart of BOARS, said this week he fully supports the decision not to retreat from Algebra II as a base of knowledge. But he also favors qualifying non-traditional fourth-year math courses that strengthen quantitative reasoning. He said he hopes the UC math workgroup drafts standards or learning outcomes for data science to distinguish between electives and advanced math courses.

Gould said he would need to review the possible criteria before deciding whether to revise the content of Introduction to Data Science.

“A data science education is essential for all students, and all students deserve a relevant and useful math education,” he said. “Despite the committee’s decision, we think it’s important that data science and statistics courses continue to qualify as fourth-year math courses.”